Jennifer Padgett on Robert Smithson

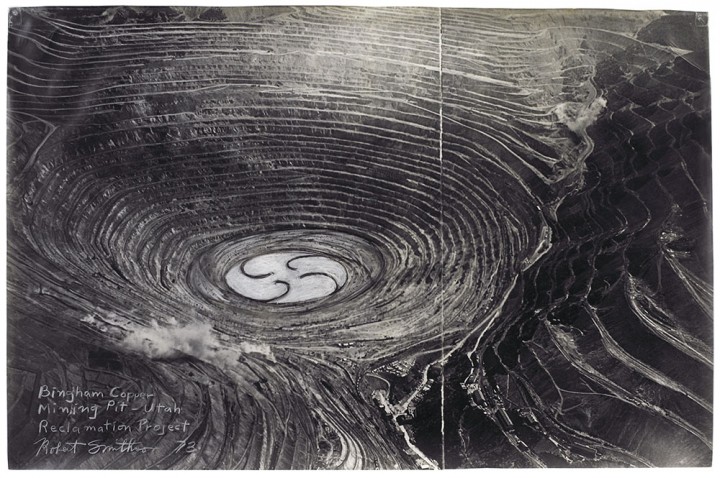

Figure 1. Robert Smithson, Bingham Copper Mining Pit – Utah Reclamation Project, 1973

Wax pencil and tape on plastic overlay on photograph, 20 x 30 inches (50.8 x 76.2 cm)

Art © Estate of Robert Smithson/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Robert Smithson

by Jennifer Padgett

Robert Smithson combined drawing with photography in Bingham Copper Mining Pit—Utah Reclamation Project (1973; fig. 1), a presentation work that is part of his Reclamation series. He began with a photograph of a specific site—the Bingham Copper Mining Pit in Utah—and then superimposed his drawing on it by placing a transparent plastic overlay on the image and sketching his proposed intervention on the surface in white wax and black pencil. The object is engaging; employing both preexisting and imagined forms, it invites the viewer to envision the site transformed by the installation. Smithson’s design features a revolving disk with four evenly spaced hooklike lines on a white ground; placed at the bottom of the pit, it appears to spiral in a vortex movement toward its center. The composition and detail of the photograph draw the eye to the disk, which is placed at the center of the visual field. The stepped walls of the pit resemble natural forms such as tree rings or the sedimentary layers of earth’s crust, and the sense of scale suggests epic and overwhelming forces at work.

Smithson prepared the drawing-photograph as part of a proposal to the Kennecott Copper Corporation, the owner of the mine, in the hopes of obtaining permission to construct an earthwork at the site. Through his reclamation series, he intended to recover spaces already transformed by human activities such as commercial mining and other destructive industrial processes. He claimed, “One practical solution for the utilization of such devastated places”—including the Bingham Copper Mining Pit—“would be land and water re-cycling in terms of ‘earth art.’”1 This position was characteristic of the Land art movement emerging in the late 1960s and 1970s, in which artists pursued a greater awareness of the environment and the effects of human activity on nature through the construction of site-specific works. Smithson—like his wife, Nancy Holt, and other Land artists—often positioned large-scale works outside the traditional gallery setting, looking to the expanses of the western United States as a terrain rich in sites for massive interventions that would call attention to ecology and natural forces.

The Bingham project was never realized, as the Kennecott Corporation apparently ignored the proposal and Smithson died in an airplane crash later in the year. While the drawing remains as an illustration of an artwork that could have had a transformative effect on an unlikely space, it also exemplifies Smithson’s particular approach to the artistic process. Rather than emphasizing the cultural value of a project or sculpture in material form, he imagined a greater fluidity among the various processes involved in being an artist, making a point of not privileging one category of art production over another according to a traditional hierarchy. The numerous manifestations of a project—in drawing, photography, or site-specific installation—could expand the boundaries of the creative process, as the inclusive work of art is not limited to one object or physical form.2

Figure 2. Robert Smithson, Shed with Asphalt, 1970-71

Graphite on paper, 20 x 25 inches (50.8 x 63.5 cm)

Art © Estate of Robert Smithson/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Smithson’s pencil drawing Shed with Asphalt (1970–71; fig. 2) has no direct correlation to a specific earthwork, yet it relates to other projects in his oeuvre and again illustrates how the artist used various mediums to synthesize the themes that interested him, including entropy and its effects on both natural and man-made elements. Smithson drew the basic form of a four-sided building viewed from the side, with a slight tilt toward the viewer so that the top of the structure is visible. Nebulous forms, representing flowing asphalt, ooze across the roof, out the windows, and onto the ground surrounding the shed. The asphalt is depicted as an entropic force that overwhelms the simple structure. Smithson was attracted to asphalt as a material that was derived from natural sources yet manufactured for use in modern construction. Its viscous quality implies a certain dimension of time in its slow movement across a surface. This drawing is not a naturalistic treatment of the properties of asphalt but instead provides an imaginative view, animated by busy pencil lines.

The drawing somewhat recalls Partially Buried Woodshed (1970), a realized work in which Smithson piled twenty truckloads of earth onto a woodshed until it collapsed. It also references the material used in his Asphalt Rundown (1969), in which he poured a truckload of asphalt down a quarry wall in Rome. By synthesizing elements from these two works in this drawing, Smithson took advantage of the flexibility of the medium as a match for his great capacity for rethinking and expanding upon his ideas.

Notes

1. Robert Smithson, “Untitled, 1971,” in The Writings of Robert Smithson, ed. Nancy Holt (New York: New York University Press, 1979), 220.

2. Jack D. Flam, introduction to Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack D. Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), xviii.

Bios

Jennifer Padgett

Robert Smithson