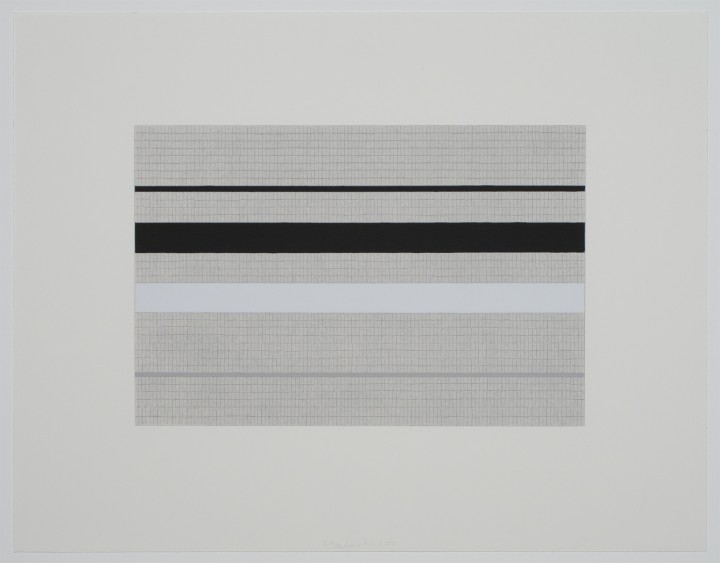

Figure 1. Frank Badur, Untitled (Fin), 2010

Gouache and graphite on paper, 14 1/4 x 18 inches (36.2 x 45.7 cm)

© 2012 Frank Badur

Frank Badur

In Conversation with Wynn Kramarsky & Rachel Nackman

August 2012

Frank Badur: The process of making a drawing begins with an impulse. Very often my drawings stem from my interest in architecture or in nature. I may also be thinking about music, Asian philosophy, or Asian poetry. But—and this is important—my work is never narrative; those sources provide only the impulse to start my drawings.

I don’t follow any system. The process of making a drawing, for me, is not systematic. If I’m in my studio and I’m absorbed in making a drawing, then the drawing tells me what my hand has to do next. The only things that are predetermined about each drawing are the measurements of the support and its orientation. Often the drawing starts with a very simple grid, and then I start to form my idea. The process develops more or less intuitively.

Like the Taoist yin and yang, my freehand irregular graphite grids provide a complementary contrast to the very precise work I do with gouache and a ruler. I like this contrast. I see the irregular grids as diagrams of my awareness as I go through the process of drawing. It’s very interesting for me to look at a drawing and to see how engaged I was, or how anxious, or how quiet my environment was.

Rachel Nackman: The freehand irregular grids can be read as a record of your mental state while making the drawing?

FB: Absolutely. Color is also an extremely emotional medium, and for me it too creates a very specific atmosphere. If you look at my drawings, I think you can observe all kinds of different color atmospheres. I have a huge color memory from my travels—you could call it a virtual color library. This is what I use in my studio.

For example, when I was in Kyoto, I was absolutely overwhelmed by the Katsura Imperial Village—by the balance of symmetry and asymmetry in the architecture, by the use of very pale colors. Years later I remembered what I had seen there, and it influenced a whole group of drawings. However, the reference is never direct; color is just something that comes back to me, and then I use it.

Wynn Kramarsky: You’re saying that your drawings are not reproductions of things you’ve seen in your travels, but they’re records of your emotional responses.

FB: Right. That’s also how I came to understand Agnes Martin’s paintings. I was in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and I thought: “Wow! These horizontal layers of light, of desert, of color—that’s what I see in the paintings of Agnes Martin.” Her work is not narrative or directly referential, but I think that she was attuned to color impulse.

RN: The impulse or the emotional response that you have to your environment then allows you to make color choices in your drawings, as well as choices about the type of line you’ll apply or about the type of grid you’ll apply?

FB: Yes. Each drawing starts out very simple, and then it becomes more and more complex. Very often I’m surprised when the drawing is finished. Sometimes I’m happy, and I can agree with my drawing. But sometimes I have to go back into it.

RN: When you have a final result that doesn’t please you or that doesn’t fit with what you were interested in achieving, you go back and rework things?

FB: Absolutely. Or I throw it into the garbage. [Laughter.] Sometimes when I make one drawing, I get the idea for the next drawing. If I’m very satisfied, then I may have the impulse to do another drawing—a third or a fourth drawing. The whole complex of my drawings grows when I’m working in my studio.

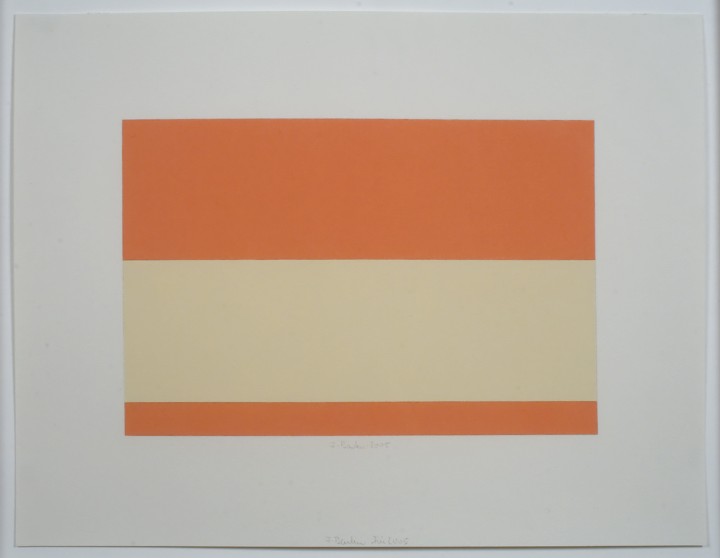

Figure 2. Frank Badur, Untitled (Fin), 2005

Gouache and graphite on paper, 13 3/8 x 17 3/16 inches (34 x 43.7 cm)

© 2012 Frank Badur

RN: Can you then look back at a body of work from a certain period and read a certain linear progression in the drawings that you made during that time?

FB: Yes. I can see my passing interests or my notions about other artists’ works. I can read all of this.

WHK: You first came to the United States in the early 1980s, and you’ve said that your exposure to contemporary American art at that time was eye-opening. Were you also exposed to Native American artwork while visiting the States?

FB: Yes. After my first trip to the United States in 1982, I returned many times to visit the Southwest. I went hiking with the Navajo Indians, and I learned about Navajo, Hopi, and Pueblo culture. Many of the Pueblo were potters, and I was utterly fascinated by the patterned drawings they made on their pottery. They are highly abstract, and they also have no system—it comes from the inside out. When I asked one of the oldest Pueblo potters how she made these drawings, she told me: “I don’t know. I think I get it from my ancestors, and I can do this only if I find a balance in my family and balance in nature. Only then am I able to do it.” I understood this so easily and so deeply.

RN: You found in studying Pueblo pottery that abstract pattern itself was evocative and that the artist was acting almost as a medium to deliver that pattern?

FB: Yes, absolutely. Each piece of pottery is almost like a piece of sculpture—the artist builds up the clay and smoothens the outside of the object by hand so that he or she can apply the drawing to its surface. They’re very involved with the pieces they create.

RN: What they do is develop a relationship with the support.

FB: Yes.

WHK: Occasionally you’ve used special handmade paper. Do you choose that support because you specifically want to make a drawing on handmade paper, or do you do so just because you have handmade paper available?

FB: I don’t just use the paper that’s available. I choose whatever is the right material for my technique.

RN: Can you tell us about the different mediums you use in your drawings?

FB: When I choose a medium, it’s also in order to engage with the specific characteristics of that medium. For example, if I make a woodblock print or an etching, I am working with those techniques in order to achieve a particular visual result, which I cannot find in another medium.

RN: Are your drawings then celebrations of these various mediums?

FB: Absolutely. I always have an idea of what I want to do, and to come close to the idea, maybe I need a brush and paint, or I need a pencil, or I need to make an etching or an aquatint. So the result is what leads me to the medium.

RN: The drawings on view here are made with gouache and graphite. Can you tell us what it is about gouache and graphite that attracts you?

FB: Yes, of course. Gouache is wet, and graphite is dry. To apply gouache, I use the brush; for graphite, I use my pencil. So the mediums and tools are soft and hard. These are opposite principles, like yin and yang. I like this—hard and soft, wet and dry. It’s a wonderful way to work.

RN: Can you tell us what it’s like to make these drawings?

FB: Making a drawing is usually a very slow process. Very often I work on four or five drawings simultaneously, so if one drawing needs time to dry, I focus on another drawing. It’s almost like a family—you have to figure out which child needs a little bit more attention than the others.

I think the aura of a work on paper is different from a painting on canvas. For me, drawing is very intimate, and painting is something you can feel or measure with your body. A work on paper is really in your hand: you measure it with your hand, and you hold your tool in your hand. Painting is very physical and requires a lot of distance from the canvas. With a drawing, I have a piece of paper in front of me, and I’m completely by myself and absorbed by the work. I’m in a contemplative state for hours.

Sometimes when I finish something, I realize I’m hungry and look at my watch—only to see that four or five hours are completely gone. Sometimes I have to ask myself: “How did this happen? And who made this drawing?”

RN: As you’ve said, you sometimes feel surprised by what you see.

FB: Yes. It’s almost like an adventure tour. I have an idea, and I try to come close to it. But sometimes I open a new door, a new space, and I have the freedom to make something else instead.

Bios

Frank Badur

Wynn Kramarsky

Rachel Nackman