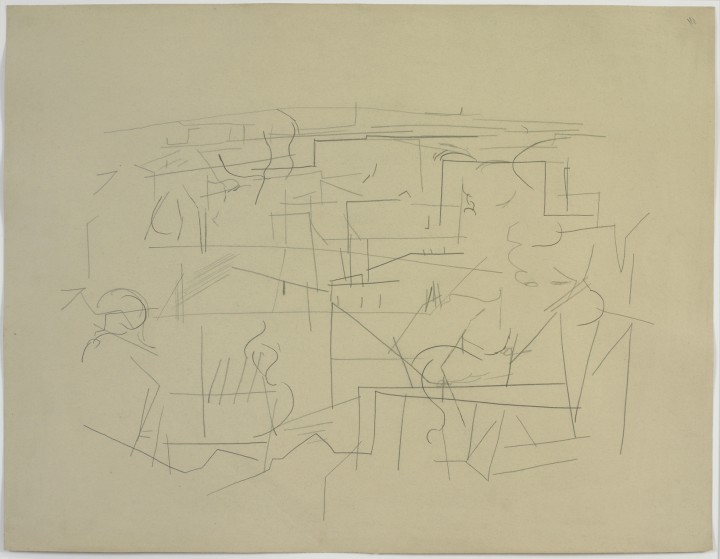

Figure 1. Ellsworth Kelly, Smoke from Chimneys, Automatic Drawing from Rue de Blainville, 1950

Graphite on paper, 19 3/4 x 25 5/8 inches (50.2 x 65.1 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, 2012

© Ellsworth Kelly

Ellsworth Kelly

by Matthew Bailey

In this loose, organic drawing of an abstracted scene of Paris, Ellsworth Kelly used the sparest of freehand notations to register the side or corner of a building, the slant and texture of a roof, and a curling wisp of smoke. Smoke from Chimneys, Automatic Drawing from Rue de Blainville (1950; fig. 1) is one of a series of drawings that Kelly executed while living in France from 1948 to 1954, in which the young artist experimented broadly with ways to “get the personality out of painting . . . to do paintings that were anonymous.”1 Employing a variety of chance procedures at this early stage in his career, Kelly embraced what the art historian Yve-Alain Bois has called a strategy of the “non-compositional.”2 Kelly’s turn toward the non-compositional was aimed at circumventing subjective expression and approaches to compositional organization that reflected the controlling will of the artist.

To create Smoke from Chimneys, Kelly enacted his own twist on the methods of Surrealist automatism, to which he had been exposed in 1949. In lieu of the Surrealist practice of relinquishing rational control in favor of unconscious processes, he instead drew scenes or objects from memory or worked “blind”—by drawing without looking at his support, with his eyes closed, or even while blindfolded.3 In this work it is likely that the artist transcribed an observed scene without looking at the paper and without monitoring his progress. This mode of working was a direct attack on conscious “motor control,” as Bois notes.4 Kelly’s method is revealed here in the way lines and forms haphazardly overlap and intersect, presenting a jumbled mass of curvilinear scribbles and irregular rectilinear contours that lose their representational function. At the same time, the drawing inevitably retains a sense of the impulse toward rational composition that the artist wished to purge from his work, a problem of which he was aware.

The composition is symmetrically centered on the paper, exhibiting overall a balanced organization of line and form. Moreover, the illusionistic nature of the imagery and the hint of spatial recession—suggested by the perspectival lines and overlapping shapes that recede into the background—also reveal a certain retention of control. As Bois has said of Kelly’s work in this series, “with this move a point of view is implied, and thus a subjective agency.”5 Plagued by the resurgence of rational control and subjective choice in automatic drawings such as this one, Kelly thereafter turned to more systematic strategies of chance, reduction, and serialization—including the creation of collages through random numerical drawings, the execution of monochromatic paintings, the use of grids, and the repetition of form—in an attempt to repress his own artistic agency.

Notes

1. Ellsworth Kelly, “Interview: Ellsworth Kelly Talks with Paul Cummings,” Drawing 8 (September–October 1991), quoted in Pamela Lee and Christine Mehring, Drawing Is Another Kind of Language: Recent American Drawings from a New York Private Collection (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 1997), 98.

2. Yve-Alain Bois, “Ellsworth Kelly in France: Anti-Composition in Its Many Guises,” in Ellsworth Kelly: The Years in France, 1948–1954, ed. Yve-Alain Bois, Jack Cowart, and Alfred Pacquement (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1992), 9–36.

3. Bois, “Ellsworth Kelly in France,” 24–25; Bois, “Kelly’s Trouvailles: Findings in France,” in Ellsworth Kelly: The Early Drawings, 1948–1955 (Cambridge: Harvard University Art Museums; Winterthur, Switzerland: Kunstmuseum Winterthur, 1999), 23.

4. Bois, “Kelly’s Trouvailles,” 23.

5. Ibid., 19.

Bios

Matthew Bailey

Ellsworth Kelly