Figure 1. Kristin Holder, Heavy Thinking (His View), 2007

Graphite on paper, 12 x 11 1/2 inches (30.5 x 29.2 cm)

© 2012 Kristin Holder

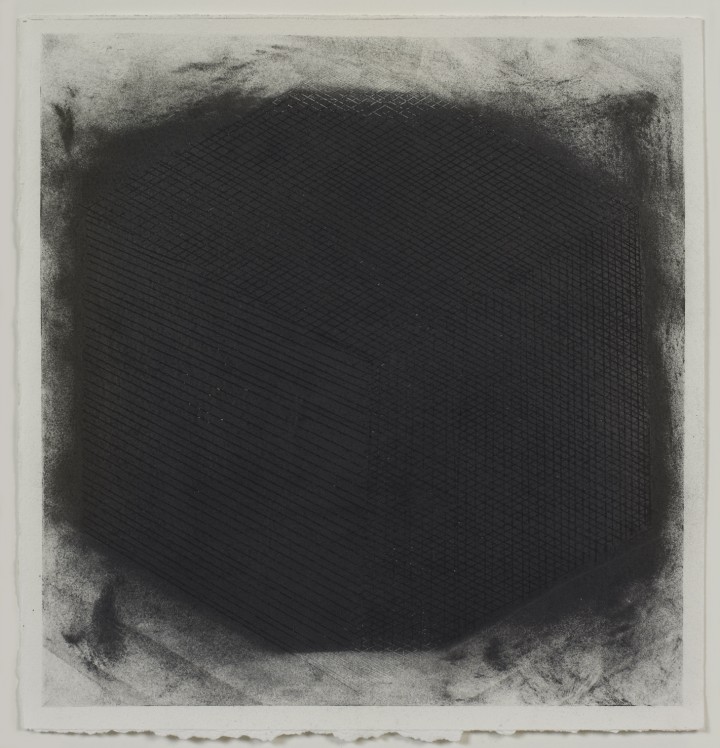

Figure 2. Kristin Holder, Heavy Thinking (Her View), 2007

Charcoal and graphite on paper, 12 x 11 1/2 inches (30.5 x 29.2 cm)

© 2012 Kristin Holder

Kristin Holder

In Conversation with Rachel Nackman

April 2012, New York

Rachel Nackman: Each of these drawings was made through very heavy surface application of graphite onto paper, incised with a series of lines that define a dimensional object. Can you tell us more about making these drawings and the materials you used?

Kristin Holder: First, I taped off the edges of the paper. I found the center of the sheet using a pencil. I constructed a cube within the taped edges. I incised lines into the paper using a burin, a tool for printmaking; those lines define the sides of the polyhedron. Then I rubbed on the powdered graphite with my hand. I used a good deal of powdered graphite in order to try to fill in all the troughs in the drawing. The graphite is just like baby powder; it goes everywhere. That’s why it extends beyond the edges of the incised lines.

RN: How did you construct this polyhedron shape?

KH: I used really simple geometry. I found the center of the sheet by drawing straight lines from opposing corners and making an X. Then I built out from that center point. For these drawings, I tried to eyeball it. I drew a circle using a compass, I made a hexagon within the circle, and then I drew a cube from the hexagon. Then I started slicing off corners in order to approach the shape that’s in Albrecht Dürer’s print Melencolia I (1514).

RN: The drawings are both titled Heavy Thinking. You made a wall drawing in 2007 with the same title. Can you tell us how, if at all, the wall drawing relates to the drawing?

KH: These drawings aren’t related to the wall drawing as preparatory drawings. They’re not related in terms of scale either. The only similarity is in the medium. Both works are made with graphite, and they’re both rubbed onto their support. The idea for both also comes from that print by Dürer, in which a polyhedron plays a significant role. The print is kind of a warning to artists not to let their practice fall too much on the side of the intellectual.

I decided to pull that polyhedron form from Dürer’s print and start working with it as a warning to myself. Don’t overthink. Don’t become too involved in the intellectual side of things. Try to make sure there is a balance between your appreciation of a drawing as you make it and the physical properties that come out of making, which are more in the realm of beauty and the spiritual.

I’ve drawn the shape from two different perspectives. His View (fig. 1) is the artist’s view of the shape as you look at it in Dürer’s print. Her View (fig. 2) shows the object rotated ninety degrees—from the muse’s point of view.

RN: Is there a reason why that polyhedron in particular catches your eye?

KH: Before I was working on these drawings, I was thinking about fractals a lot, and I was making some other wall drawings. One of those wall drawings was based on a fractal form—a kind of a branch shape. I had made a stencil out of the branch shape, and I used it to create a larger form that looked kind of like a feather or a tree—just by repeating this shape and following a very mathematical way of growing it.

Occasionally I get overly engrossed in the mental intricacies of an idea and go too far with it. After seeing the Dürer print, I kept thinking about that polyhedron. I couldn’t figure out what it was—or where it derived from in the first place. So I started drawing it to try to figure it out. I determined that it was a cube, and it took off from that earlier idea of studying the cubic fractal.

RN: Can you provide a basic overview of fractals?

KH: A fractal is a mathematical construct. It is a way of studying forms that look the same whether you’re viewing them from a 1x magnification or a 1000x magnification. Fractals are used to study clouds, trees, river tributaries, coastlines—things to which you wouldn’t think you could apply a mathematical formula. These drawings are in no way representations of a fractal, but that was a jumping-off point.

It’s hard for me to say that drawing a cube would be intuitive, but the cubes in His View and Her View are intuitively made. I eyeball a lot of it. I use a really simple way of finding the center of the drawing, using and making tools, and then rubbing. So there’s not a lot of math involved. There’s no form that can’t be intuitive. I think that’s a frame of mind.

RN: And these drawings are an exercise in that frame of mind?

KH: Yes. It was something I set out to change in myself. In these drawings, I think I needed the progression and the steps. I think that being physically involved in the making, letting it become more of an intuitive process, has been really healthy for me.

RN: In a statement that you wrote in 2007 about your wall drawing Heavy Thinking, you mentioned that you made the work in two phases: the first phase was concerned with line, and the second, with mass. Was there a similar distinction in making these drawings?

KH: Not so much. When I was making the wall drawing, the line was set up purely for me to fill in—in order to draw an object that is to scale. Making the wall drawing was extremely enjoyable because I was working freehand on a twenty-foot wall—so the line had a lot of give and play, and I reacted to myself trying to keep it straight. It shows in the final drawing that line and mass are really separate, because the graphite area is hard-edged, heavy, matte, and the line drawing is erratic—it has a whole different quality.

In the works on paper, line and mass are intertwined. I see the incised lines as part of the drawing. Each line becomes a cavity to hold the graphite, and there’s no separating them for me.

RN: We’ve talked about the Dürer print quite a bit, but you’ve also spent some time at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, installing Sol LeWitt wall drawings. Did that experience, or your experience with LeWitt in general, have any bearing on these drawings?

KH: I think the most direct correlation between these drawings and LeWitt’s wall drawings would be the sound of making these drawings. When I made a LeWitt wall drawing, it was a noisy, repetitive movement, done with lead pencils on a bumpy wall. You could hear the sounds of the pencil, and that made a lasting impression. When I am making my drawings, there is a similar kind of grating sound, especially when I am incising the lines, because my burin tears at the paper a little bit. I think the similarity of sound is the most pertinent relationship here.

But I don’t think there’s any way that I could really extract the legacy of Sol LeWitt from my work—split it into pieces or parts that are particularly relevant. I think his work is a visual language that’s part of me.

RN: You also spent some time working in conservation at the National Gallery, which must have given you an understanding of materials, beyond just how they’re used.

KH: Yes, it did. The benefit to me from working in conservation lay in seeing all the underdrawings beneath paintings. I was interested in unraveling the processes of other artists. Artists use their materials with a great deal of respect. They may have a lot of expectations for the materials, and they may not understand the chemistry behind them, but they make it work.

RN: From one angle, these drawings were an intellectual project, through which you were changing the way that you approach making work. But was this also a material project? Was this in part an effort to get to know something about graphite, something that you didn’t already know?

KH: I think a lot of great work is made when the artist is working with materials that he or she doesn’t know. As you work, you push your materials farther and farther, but you don’t ask them to do more than they can. I have some understanding of what graphite can do. What I want it to do is stick to the paper, and that’s about as complicated as the question gets. So I use a burin to try to make a place for the graphite to stick to the paper. Step by step. I wasn’t trying to find out something new about what graphite can do. I didn’t set out to do it, but along the way I did.

Bios

Kristin Holder

Rachel Nackman