Matthew Bailey on Donald Judd

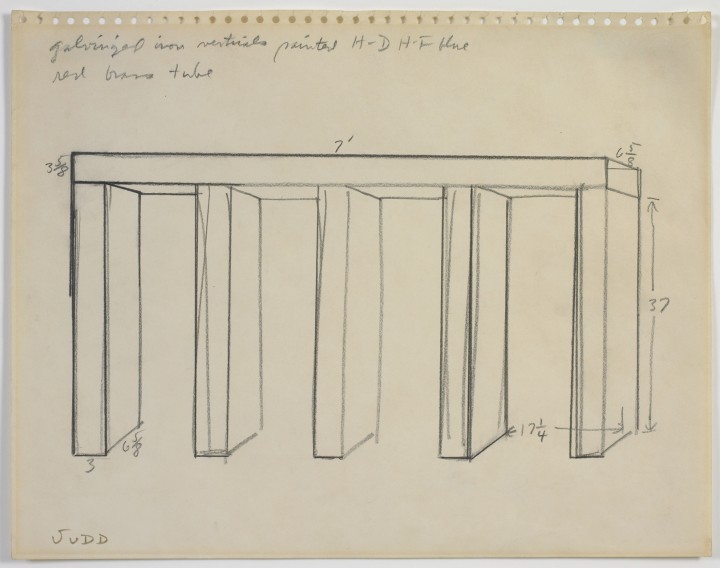

Figure 1. Donald Judd, Untitled, 1967

Graphite on paper, 10 3/4 x 13 1/4 (27.3 x 33.7 cm)

Art © Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Donald Judd

by Matthew Bailey

Donald Judd was one of the leaders of Minimal art, both as an artist and as a critic. His sculptural works, which he labeled “specific objects” in a seminal essay published in 1967, were characterized by streamlined large-scale geometric forms produced using industrial materials and processes of fabrication. Judd’s untitled sketch, also from 1967 (fig. 1), is a working drawing for one of a series of sculptures that he began producing in 1965. Each nearly identical object in the series consisted of a horizontal bar with five verticals, yet each displayed slight variations in materials and colors. The schematic work on paper includes handwritten notations for color and material, along with precise measurements for each plane of what Judd called “the brass with five verticals.” The drawing demonstrates the artist’s graphic distillation of “above all that shape.”1

By using aesthetic strategies such as symmetry and repetition, Judd strove to create an indivisible, unified three-dimensional form in which no particular element assumes visual or compositional focus. This was his way of avoiding what he called “the problem of illusionism” in traditional painting and sculpture: the use of compositional hierarchy emphasizing parts over the whole and the consequent allusion to some other symbolic world beyond the work of art itself. Instead, his literal objects were meant to assert their own holistic presence in “real space,” something “intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface,” as he wrote.2 Judd also deflected the associations carried by traditional art materials and circumvented the intrusions of subjective expression by having his objects manufactured by skilled laborers using industrial materials, thus distancing the artist’s hand from the act of making.

Judd’s Minimal forms were aimed at generating perceptual and phenomenological responses in viewers, enhancing their sensory awareness of physical space.3 Pictorial by nature and executed by the artist’s hand, this preparatory drawing seems antithetical to the cold, impersonal nature of his substantial objects. It also demonstrates the kind of perspectival illusionism that Judd wished to evade in his “specific objects.” It is no wonder that he diminished the importance of his graphic studies, claiming that they were “simple mechanical instructions for the production of standardized forms with industrial materials.”4 That he did not think of these as polished works for exhibition or presentation is demonstrated by the casual, schematic use of contour lines with no concern for shading, detail, or color.

Nonetheless, these diagrammatic sketches were a crucial component of Judd’s practice. As he once mentioned, they were a means of recording ideas for both past and future works.5 As such, these kinds of drawings served as an arena in which he experimented with and worked through abstract conceptions, demonstrating an incipient stage of his creative process in which he utilized the flexibility of the medium to sketch, notate, and diagram shapes, dimensions, colors, and materials. The cognitive immediacy reflected in his drawings is made tangible in the lightly drawn, cursory lines that he used to define the essential structure of the horizontal and vertical bars, over which he marked heavier and more decisive contours with the aid of a ruler to give his study a more detached, mechanical quality. For all Judd’s emphasis on the phenomenal experience of the three-dimensional objects themselves, without allusions to the artist’s hand or creative praxis, studies such as this reveal the degree to which he relied on drawing as a means of reconciling formal and theoretical abstractions—a practice he shared with many artists associated with Minimal, Conceptual, and Process art in the 1960s and 1970s.

Notes

1. Bruce Glaser, “Questions to Stella and Judd,” Art News 65 (September 1966): 58.

2. Donald Judd, “Specific Objects” (1965), in Complete Writings, 1959–1975 (New York: New York University Press, 1975), 184.

3. David Joselit, American Art since 1945 (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2003), 113.

4. Josef Helfenstein, “Concept, Process, Dematerialization: Reflections on the Role of Drawings in Recent Art,” in Drawings of Choice from a New York Collection, ed. Josef Helfenstein and Jonathan Fineberg (Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2002), 15.

5. Dieter Koepplin, introduction to Donald Judd: Zeichnungen / Drawings, 1956–1976 (Basel: Kunstmuseum; New York: New York University Press, 1976), 8.

Bios

Matthew Bailey

Donald Judd