Karen Schiff in Conversation

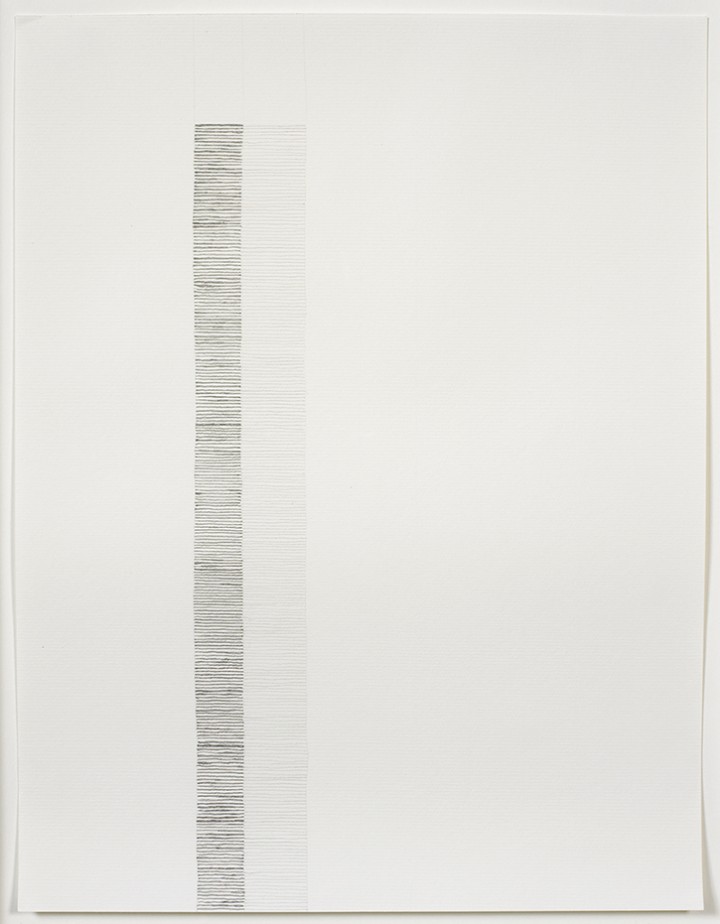

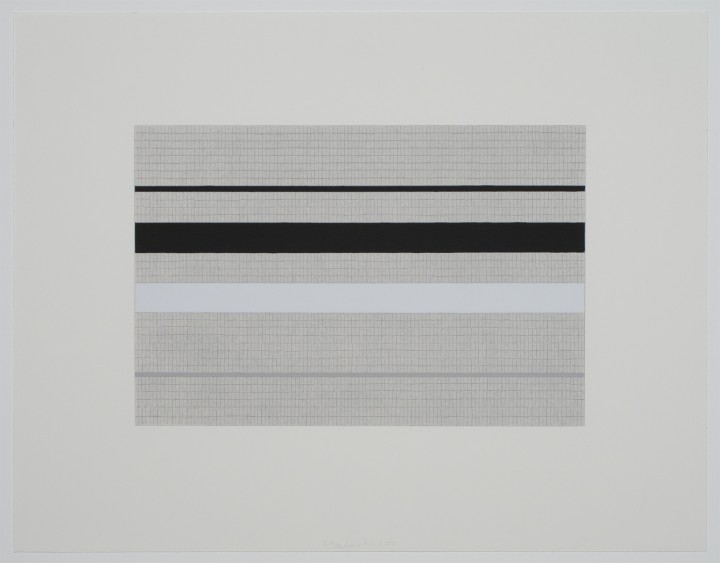

Karen Schiff, Untitled, 2006

Graphite on paper, 15 5/8 x 12 inches (39.7 x 30.5 cm)

© 2012 Karen Schiff

Karen Schiff

In Conversation with Wynn Kramarsky & Rachel Nackman

March 2012, New York

Rachel Nackman: How did the Laid Line drawings develop?

Karen Schiff: The Laid Line drawings came out of my concern about being able to relate directly to the physical world. Before I started this series, I was making rubbings of floors, getting a sense of a texture that isn’t immediately available to the eye. The Laid Line drawings were an attempt to get at the texture of paper, which one also can’t necessarily see. But I knew that I couldn’t just rub my pencil over the surface of a sheet of paper and make that texture visible. I had to articulate it more closely.

Both the rubbings and the Laid Line drawings perhaps grew out of my practice of meditation. A lot of people think that meditation is about going somewhere in your head—a nice beach or some fantasyland. But my experience of meditation is that it’s simply and literally a practice of being in touch with what’s actually happening and with the world that’s around us. And it’s “practice” for doing that all the time. The techniques that I use in my drawings are material ways of bringing that practice into my art making.

RN: So you’re trying to “get in touch” with the paper, to enhance your own understanding of its character?

KS: Yes, I want to “understand” the paper but through the senses. And I want to give that sensory experience to the viewer as well. Paper is the underlying substrate of so many drawings. In the Laid Line drawings, the physical object is highlighted. The drawings invite viewers to have a visceral experience of what is immediately in front of them.

RN: Does the drawing act as a scrim over this object: a screen through which you hope people will see the paper in a different way?

KS: It is a scrim—in the sense that I’m layering graphite over the paper. But I actually want that layer to act as more of a conduit. I want to lift a veil between the viewer and the object.

Wynn Kramarsky: Clarifying is probably a good word for that.

KS: Yes. I highlight or articulate the paper, clarifying our view of what we can’t so easily see.

WHK: For a fairly general audience, I think it might be good to distinguish between laid and wove paper.

KS: Sure. The laid paper I’m working with is made on a mold, with a mesh of very fine wire ribs. The resulting paper is embedded with a perpendicular grid that looks like books on bookshelves. That laid texture intrigues me—maybe because it reminds me of Agnes Martin’s grids but also because it’s a clearer texture than you can see in wove paper. Papermaking molds for wove paper have a very dense, interlocking wire structure, which results in a more uniform, allover texture.

RN: When you make other drawings, do you work primarily with laid or wove paper?

KS: Neither. I actually avoid making other types of drawings on textured papers because I find the texture so distracting. One of the sources for this idea was a Vincent van Gogh drawings exhibition that I saw at the Metropolitan Museum of Art [Vincent van Gogh: The Drawings, October 18–December 31, 2005]. I kept looking at the papers Van Gogh used because their textures and colors were so intriguing. I was thinking, “How can he be making all of these marks on the paper, when there are already so many marks in the paper?”

RN: When did you make your first Laid Line drawing?

KS: It was in 2006, when I was on a residency at Jentel in Sheridan, Wyoming. The drawing in this exhibition is from the pad of paper on which I first started tracing the Laid Lines. I had the idea maybe a year earlier, and as with lots of my ideas, it sprang fully formed into my head, but I let it simmer for a while. In this case it finally reemerged because I found this particular pad of paper—and I make Laid Line drawings only on paper that speaks to me in some way. If the paper is materially intriguing, then I want to work with it, to bring attention to whatever it is about it that I find qualitatively interesting.

RN: Why was this particular pad of laid paper intriguing to you?

KS: It had nice proportions—I liked the seventeen-by-fourteen-inch size. It had a good color, a good weight. For those reasons, I bought it, but when I got back to the studio and looked at it more closely, I realized that there were all kinds of anomalies in this paper that made it even more interesting. The columns in this main space of the paper—they’re called chain lines—are not always evenly spaced. Sometimes they’re bending or curving! That’s what intrigues me so much about this project. When I engage with real paper, it’s not ever what I expect. My goal is to bring out those anomalies.

I should say also that this is machine-made paper. I use only machined papers in the Laid Line drawings; I don’t use handmade papers. I have a sense that daily, seemingly boring materials are actually quite unusual the more you look at them. These machine-made papers, which try to be so regular in their manufacture, actually contain surprising details. The more we look at our daily surroundings, the more surprised we might be.

I want to show the human quality in machined material. That human quality comes out of the paper—not only in the bending chain lines, but whenever I clarify or articulate these details, my hand also makes mistakes. Variations come from me as well as from the machine.

RN: By applying graphite to the paper, you bring all these imperfections to the surface.

KS: Yes. I use only tools that will respond to my hand—graphite, ink—but applied with a brush or a dip pen so that there is variation in the mark.

RN: How do you decide where on the page you’re going to begin drawing?

KS: I hold the paper up to the light and examine it. What I’m looking for are the places where there are bends in the chain lines, where the widest and narrowest columns are. . . . This particular pad of paper had an anomalous horizontal seam that fell at a different place on each sheet—an extra bit of raised texture. In this drawing, I found where that horizontal seam fell within the field of the sheet, and I used that to determine the location of the top edges of these two columns.

RN: Is that sort of decision based in any additional way on the formal composition that you’d like to develop? Or are your choices based entirely on the conditions of the material?

KS: It’s some of both. In this drawing, the dark column is the narrowest column in the whole field, and the lighter column is the widest column in the whole field. I was really interested to see what it would look like to make a drawing of just those anomalous columns.

When I make drawings in which more standard columns are involved, I annotate those columns in a medium gray, in terms of the density of the graphite. I decided that if I were to squeeze the graphite—to fit into the narrower column—it would get denser and therefore darker. And if I stretched it out like taffy—to fill the wider column—it would get lighter. That was my color-coding key for this series.

RN: Do you feel that it’s important for a viewer to understand what you are doing on each page, why your marks are arrayed in a certain way?

KS: I think that each drawing—if it’s working—has its own life. I don’t need to say anything about it. Ideally, if somebody looks at it long enough or hard enough, the source for the marks will reveal itself.

WHK: That assumes that people know enough about paper to begin with.

KS: In a way, I don’t assume that people know anything about paper.

WHK: Do you hope that your drawings will teach them something?

KS: Yes, or bring them to appreciate the paper visually, even if they don’t know how those creases are made.

WHK: It’s a leap of faith.

KS: It’s a hope. I’m really interested in bringing out the art in the everyday or the artisanship in the machine. That’s partly because I’m distressed at the way that culture seems to be veering so far away from valuing craftsmanship. Through these drawings, I’m saying, “There is actually craftsmanship here—even in the stuff we think doesn’t have it.”

RN: What do you think about while doing the repetitive work involved in a Laid Line drawing?

KS: I’m thinking both of keeping track of where I am and of anything else that happens to be in my head. I hope that the process reveals not only the actuality of the paper but also the moment-by-moment engagement of my hand.

Paul Klee used to say that drawing is taking a line for a walk, but when I make these lines, I feel like I’m walking hand in hand with the line. When you’re walking with somebody, holding hands, you are aware of holding hands with that person, but your mind can be anywhere. If I’m too fixated on these lines, the whole process feels so tight that I get exhausted, and I think that the drawing suffers as a result. If I’m too loose with my attention, I’ll go beyond the margin, or I’ll otherwise lose track of where I am on the paper. I need to have my mind somewhere in between paying attention to the physical act and not paying too close attention. It’s like a light touch—an awareness with an aerated quality.

RN: Is this a frame of mind that you enjoy?

KS: Yes. It’s relaxing, both because I enjoy working with the paper and because it’s a frame of mind that feels generous toward my own thoughts, which could involve anything.

RN: These drawings do so much to clarify and annotate your materials, but are they ever about you?

KS: I was just thinking about the word clarifying and how it relates to butter. When you clarify butter, you separate out the parts, but also it becomes much more rich, and it tastes good. That’s something about me that I hope comes through in these drawings: an expression of my appreciation for these materials. Even though the genesis of these drawings is conceptual, they also come from a deep love of material that I hope people will pick up.

WHK: I think any good drawing is a self-portrait. Maybe it’s totally abstract, but it is an expression of whatever that artist is trying to communicate. It is very important that you’re a part of this, intrinsically, because without that involvement, the drawing would not exist.

KS: I’m showing you my priorities here—and my priorities are, to some degree, getting beyond myself. My contribution is to say: “Look at this paper! Isn’t it cool? There’s so much to it.”

WHK: It’s interesting that, even with that kind of concern for the material, you decided to use machine-made paper rather than handmade paper. For many people, the idea of paper being handmade is very important, and they want to communicate that. Your approach is more twenty-first-century.

KS: Yes. Well, I’m not just concerned with this piece of paper. I’m concerned with the world to which it belongs. If it’s handmade, then the world that it belongs to feels almost hermetically sealed—enclosed in craft. This paper does belong more to the twenty-first century.

RN: While you were beginning this series, you were also conducting research on contemporary music. I imagine that as you make each drawing you develop a rhythm of making that drawing.

KS: Yes. That’s so true. The tool changes the rhythm, and it develops into a way of spending time or thinking about time.

RN: Or marking time.

KS: Yes, literally. That’s another way I think about these drawings: each of these lines is a separate moment. Each is like a character in a language that we don’t yet understand. Each character is unique, even though it’s the same type of mark.

RN: You’ve said that perhaps what attracted you to laid paper was its reference, in your mind, to Agnes Martin’s work. Agnes Martin has been very important to you throughout your practice.

KS: For me, Agnes Martin is a model of rigor and of honoring a certain aesthetic standard and work habit. Her works exhibit a mixture of a human touch and a regular, quasi-mathematical sense of proportion.

My Laid Line drawings are gridded, as much of her work is gridded, but the sources for our grids are completely different. She would have a feeling, an “inspiration,” and she would wait until she could envision whatever geometry was going to make manifest that particular feeling. This was a romantic activity, and in a way I’m a romantic too. But my romance is with something very real-world. I look to material reality for my inspiration. It’s my contact with reality that inspires the work.

Play to hear Karen Schiff discussing awareness and intention in her work.

Bios

Wynn Kramarsky

Rachel Nackman

Karen Schiff

Sharon Louden in Conversation

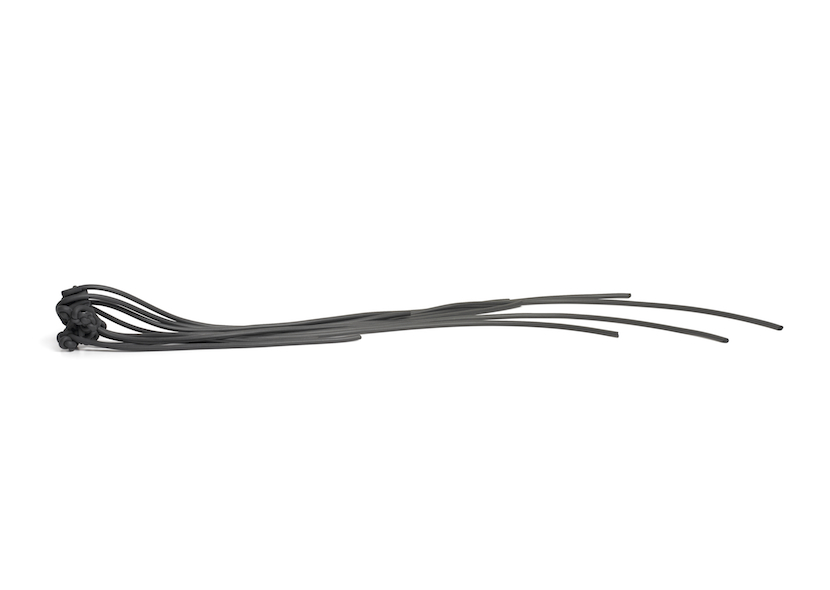

Figure 1. Sharon Louden, Agent, 2010

Foam rubber and glue, 36 x 7 x 3 1/2 inches (91.4 x 17.8 x 8.9 cm)

© 2012 Sharon Louden

Sharon Louden

In Conversation with Wynn Kramarsky & Rachel Nackman

March 2012, New York

Rachel Nackman: When you’re working on a particular series, is there a progression from works on paper to sculpture? Or do you work on a plurality of media at the same time on a similar theme?

Sharon Louden: I work on everything at the same time. I don’t really see a difference between drawing on Mylar and drawing with rubber. I see it as very similar.

Wynn Kramarsky: For you, shaping these objects feels similar to drawing?

SL: I decided to start making sculpture because I wanted to be able to embrace forms; I wanted to feel them. I asked a sculptor, “How do I get into this?” And he said, “Just pick materials that feel like the marks that you make.” So I picked rubber initially because I can mold it in the same way and use a similar stroke—it’s a familiar way of using my hands to make the form. Yes, I can hold rubber, and I can’t hold paint in the same way, but for me it’s the same process. It feels different because the materials are different, but the thought process is the same.

RN: The muscle memory and the mechanics of it feel very similar?

SL: Yes. I make one mark, then another mark, next to another, next to another—pulling it out, putting back in. . . . The Agents were the first body of sculptural work that I made.

RN: You began sculpture working with this rubber tubing?

SL: That’s correct. I initially used pins because I wasn’t sure—I was tentative. Then I started using Krazy Glue and epoxy, and once it held for me very quickly, I thought, “I’ve got something here.” That’s how it started to form.

RN: So for you the immediacy of the glue drying and holding those forms together felt like adding paint stroke after paint stroke?

SL: Absolutely. One stroke, secure. Another stroke, secure. It’s exactly the same, at least in my mind. Drawing on Mylar—with the resistance that the Mylar has to paint and the way it lies on the surface and creates an elastic feeling—is about building up rather than working with something there that’s already built. But the process and where the marks go are the same.

RN: When you’re working on a drawing and working on sculptures, do those two different mediums relate to each other? How does pausing and working in one medium then affect the other?

SL: It’s about relief. If I can’t see in the sculpture so much, then I go to the drawing, and I go back and forth. Even though it’s a similar process, they’re two different things.

RN: And do they complement each other, or are they very separate?

SL: I think they totally complement each other. The nature of my work is such that all the mediums I use assist a visual vocabulary, and that visual vocabulary transcends through these different mediums to be able to speak of one thing.

RN: In this series the works are all called Agents, and you’ve said that you think of your gestures as characters. Can you tell us a little bit about the Agents and what kind of characters they are?

SL: When I think of an agent, it’s an agent for something. If you think of Bond 007, you think of an agent as somebody who’s a quiet person that is doing something for somebody else. So it immediately has a character. . . . I think that these things—since for me they imply movement and they have mystery to them—are agents for someone or something.

RN: How do the Agents differ from your other characters?

SL: [Laughter.] I think they’re funny. I think they are complex. A museum curator for whom I have a great deal of respect once said to me, “Your work is either very straight and minimal, or it’s very knotted up and complex and clustered.” And I think that’s true. I think she made a very good observation. I seek that relief, and then I find that complexity that I want too. The Agents are about the richness of energy being stored in one place—and they’re also meant to be very funny. They’re very minimal little gestures, and when they’re put together, they create a whole character. That’s very similar to the rest of my work.

For example, in the piece in Minneapolis in which I used 250,000 strips of aluminum [Merge (2011) at the Weisman Art Museum]: each piece of aluminum is hand formed. They’re all individual forms. Singularly, each one has an identity, but when they’re put together, they create a whole environment. It’s very much like the body; you have one cell that may have one function, but together with other cells, it makes the entire machine run. That’s what I’m thinking about in the work.

The Agents are very special to me because they’re the first characters that led me into three-dimensionality. They’re very funny. I now have a great relationship with rubber; it’s like one of my best friends.

RN: How did you get acquainted with the rubber tubing that you use?

SL: A few sculptors mentioned it to me when they were giving me advice. I think getting information from other artists is extremely important. Having that exchange has fed the growth of a lot of my work. So they mentioned rubber . . .

Also, of course I love Eva Hesse. When I was at Yale for graduate school—and afterward when I was finished with school—I leaned on Hesse a lot in my drawings. And I loved her sculptures; she helped me with this body of work as well. Then I had to work through her in order to become more independent from her. I love her work quite a bit, but I have to stay away from it because there’s a certain amount of vulnerability there that’s too close for me.

RN: You tried to move beyond your original attraction to Hesse, toward working with the materials and the forms that you see in her work?

SL: I think that she gave me the confidence, along with other artists who are living and breathing in this world, to work with that material. I eventually moved past her and others who influenced me.

RN: Is the rubber tubing an art-making material? Or is it an industrial material? And if so, what is it used for?

SL: This foam rubber is used for storage and shipping of cosmetics actually. It’s also used for plumbing and has other industrial uses that I’m not familiar with.

RN: Do you buy it in a long roll? Or does it come in sticks? How do you detach the gestures that you make from the original mass of the material?

SL: I have had a great relationship with Canal Rubber in Lower Manhattan since the mid-1990s. There’s a guy whom I work with there, and at first he didn’t understand why I was buying coils and coils and coils—mounds—of this rubber. They love me for that, but they’re still puzzled about why I need that much. The rubber comes in huge rolls, and I usually buy in bulk.

RN: And you’re working with glue?

SL: Just glue and epoxy, and that’s it. It’s simple.

RN: How did you decide to start working with the black rubber tubing? Is that just something that arrived at Canal and you picked it up?

SL: Yes, I saw it and it was just like the marks I was making in the drawings. Anything that looked like the marks I was making, I was going to try.

Figure 2. Sharon Louden, Drawing for ‘Agents’, 1996

Paint on mylar, 11 x 17 inches (27.9 x 43.2 cm)

© 2012 Sharon Louden

RN: When you started working with black rubber tubing, did you then start working with black acrylic, as in this drawing [Drawing for ‘Agents’, 1996; fig. 2]?

SL: No, I was already working with black acrylic. This is ink and acrylic with gel medium. I generally go with whatever I’m using at the moment. I don’t question it too much. I’m in this work, so it’s sort of automatic.

RN: It’s all about the gesture.

SL: Yes.

RN: Can you tell us about the materials in this drawing and the application of the medium to the support?

SL: A lot of people think I work with just my fingers. That’s been a recurring comment, especially in the last ten years. But this drawing was made with a brush. The way I got that circle was by going over and over and over it again, so that the paint started to recede and move to the outside edges of the stroke.

To make these drawings, I would take a stack of paper—in this case Mylar—and then I would edit the group by throwing out drawings that didn’t work. So these are quite spontaneous, of the moment, and very special.

RN: You chose to have some of the rubber Agents cast in bronze. Can you tell us about that decision?

SL: I wanted them to go outside. [Laughter.] That’s the only reason. I just wanted them to walk outside—that was it. I felt bad for them. At Rhona Hoffman Gallery in 2000, I had them cast very small in bronze, and they were put on the floor. People would walk into the show, and they would have to crouch down to look at them. I loved the power of that size—the Agents had a lot of power themselves. They were like, “We’re here too!” I loved it.

RN: Can you tell us a little bit about installing them, how they related to one another and to the space around them?

SL: It’s all about drawing. I think of using sculpture much like I do a drawing. Space is like a blank sheet of paper. The tension between those forms is determined by the way they are carved out and placed within that space.

RN: The sculpture that’s on view is a lot larger than these earlier, smaller Agents—and it has a very lengthy tail gesture.

SL: That’s right. Oh, I love it! I think that Agent is, in a way, an ugly little thing. It’s not very glamorous. But lately I have embraced more and more a sense of glee or flamboyance in the work. I wanted to extend the gesture further into space and reactivate that space with it—to create that sort of flamboyance, with a peculiar form that has this odd head. It isn’t as beautiful per se (or funny or cute), as those other Agents were. It’s just where I am in my head right now. The fact that I still love these forms and still have a relationship with them—that they’re with me as I keep growing—is important to me.

RN: Is there anything that you consider crucial to the installation of this Agent that you wouldn’t want someone to change?

SL: If that little Agent was flat on its back (the poor thing), that would be pretty upsetting. But I think that if the orientation is correct, we’re in good shape. I like things not to be centered. Once you move something off to the left or off to the right, it indicates a question: Is it entering the space? Is it leaving? Where did it come from? There’s a history then—and it also implies momentum, implies movement.

RN: It implies volition too, like the Agent itself is making some decisions that you can then question.

SL: That’s right; that’s good.

RN: Your really early history was in figuration.

SL: I still find the Agents to be very figurative—I really don’t find this work to be that different for me. I’m in dialogue with these forms, and I feel like they have a heartbeat. They’re anthropomorphic. They’re little beings. I don’t quite know what they mean sometimes, but they are important to me.

My dialogue with my work has been linear. It really developed after I left Yale, and my mentors there—Mel Bochner and William Bailey, among other people—helped me to see both the conceptual and the formal, and how they relate to each other. To this day, I will always say that I feel like I’m a formalist. I’m very traditional in a lot of ways.

In my studio now, I don’t think about drawings and paintings and sculpture. I don’t think about it that way anymore. It’s across the board what it is. Some people call me a sculptor, but I don’t look at myself that way. I think all my work is part of a visual vocabulary—my truest expression.

Drawing is an act. It’s an extension of my hand. In whatever manner I use that hand, with whatever medium—my hand is still there. Some people call it painting; some people call it drawing. I love the fact that this debate is there. Because it is what it is. [Laughter.] It’s a piece of work!

Play to hear Sharon Louden discussing sculpting with rubber.

Bios

Wynn Kramarsky

Sharon Louden

Rachel Nackman

Nicole Phungrasamee Fein in Conversation

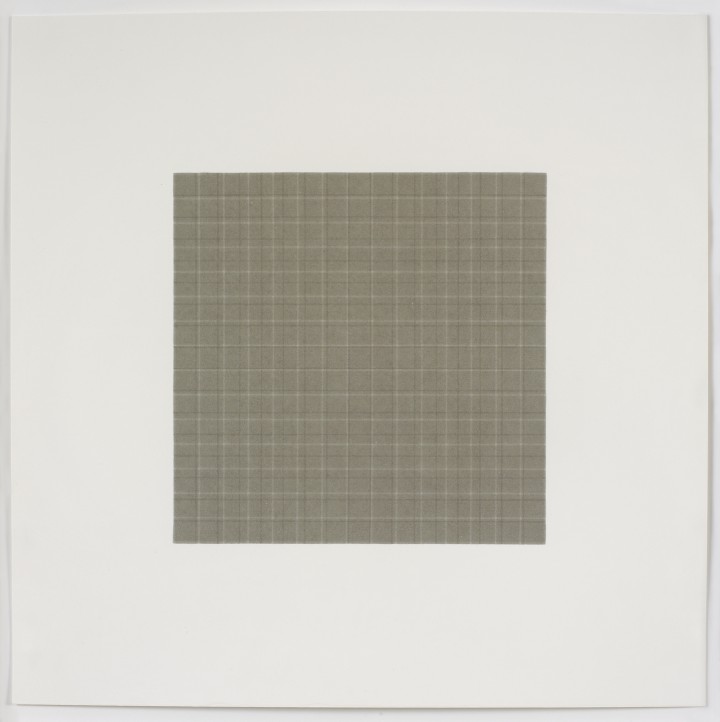

Figure 1. Nicole Phungrasamee Fein, #1042809, 2009

Watercolor on paper, 15 x 15 inches (38.1 x 38.1 cm)

© 2012 Nicole Phungrasamee Fein

Nicole Fein

In Conversation with Wynn Kramarsky & Rachel Nackman

March 2012, New York

Rachel Nackman: Can you tell us about the rhythm of making one of your drawings?

Nicole Fein: Slowing down is fundamental to what I do. I use processes that are technical, but the essence of the work is not the technique—it’s the process of slowing down and building something in a step-by-step, iterative manner. That is my approach to every day.

The slowing down comes from the very simple rituals of cutting the paper, setting it up, and doing tests on the test sheets. All those rituals bring me to a place from which I can make that first line.

Wynn Kramarsky: In making the initial decision to make a drawing, a particular drawing, do you think, “It’s nine o’clock on a Tuesday, and I have to make a drawing”? Or do you think, “I have to make a drawing, even though it’s nine o’clock on a Tuesday.” How disciplined are you? And how much of your work occurs because you suddenly feel that you must produce something?

NF: There’s a pressure that comes and goes—but it is like going to work. When it’s time to work, I am disciplined about bringing myself to that place.

WHK: Discipline of course can imply internal resistance. But you’re saying that your sense of discipline also makes you feel, “I must do this.”

NF: Yes, it’s both a discipline and a calling. Sometimes I can’t resist, like the times when I go downstairs to the studio—just to close up for the night—and something catches my eye, and before I know it, hours have passed and it is three in the morning.

RN: How long does it take you to make one of these drawings?

NF: The finished piece is ideally made in one sitting, but I make so many failed attempts that I don’t know whether to count those in the process of making one work—especially when I’ll complete one and it’s still not right.

RN: It could take anywhere from one sitting to several weeks of work to complete one drawing?

NF: Yes. And a sitting can last anywhere from a few hours to all day. The longest was fourteen hours straight.

RN: Can you tell us about the physical process of making each drawing?

NF: I can describe, first of all, the setup. My good friend Ed Green made me a beautiful large worktable. On the worktable is an adjustable easel. I used to draw bent over at a flat table, and it was really hard on my back and shoulders. I wanted to be upright. The easel that Ed designed allows me to turn the paper upside down to draw from both directions while also keeping the line I’m making at eye level. I start at the upper left-hand corner and move the brush from left to right, turn the board and the drawing upside down, and then go back over that line again, moving across the paper. A Velcro system allows me to adjust the height of the paper after every stroke. Through repetition, I get into a rhythm of drawing. But still, after many hours, standing or even sitting upright…I get tense and tired.

RN: Do you take breaks?

NF: I try not to take breaks. It’s best for the work that way. On a very intensive day, I won’t talk to anyone. I won’t eat very much. I try to avoid having to take a bathroom break. It’s rigorous.

RN: Do you have to prepare yourself in advance for that sort of endurance test?

NF: I don’t do anything specifically to prepare. I think it is different now than it was in the beginning, when I didn’t realize what would be required, and I would just get involved in a piece. Now that I know what it will take, it can be daunting, in the morning, to set out to do it, but…

RN: That’s when you approach the discipline that Wynn was talking about.

NF: Yes. Mentally it does require focus and patience, and I’ve often been asked whether it feels like a meditative process. I’ve never done strict meditation, but doing this kind of work requires absolute presence of mind, attention, and focus on the line at that moment. It does not leave me feeling refreshed at the end of the day. I feel completely depleted and exhausted. It’s not rejuvenating, as maybe meditation is.

One important thing to me, however, is that I do not want the drawings to feel labored over even though they are labored over. I want them to have a real sense of peace and calm, and I want them to simply appear on the paper.

WHK: When you finish a drawing and you decide, “Yes, this is a good one,” does that give you the kind of serenity that most of us experience when looking at your work?

NF: Sometimes it does, but sometimes it’s the opposite. I’ve completed a drawing and felt awful, like it’s just a disaster. This has happened a number of times, and I’ve come to bed in tears. And I wake up [my husband,] Mark, really upset, and he’ll have been rooting for me all day—hoping it goes well. I’ll tell him that the drawing is a failure. He’ll say, “Wait till tomorrow, wait till tomorrow, look at it again tomorrow.”

The next day it does look better, and the day after that it looks even better, and a week later maybe I can start to feel that sense of calm from it…. I’m learning to trust the process, to keep going even if it doesn’t seem like it’s going well. At its best, the practice brings calm.

RN: When you’re making a drawing, are you conscious of certain things that you need to do in order for it to turn out well?

NF: Absolutely. One of my long-running conflicts with myself is about trying to make a perfectly straight line. There’s some comfort in trying to maintain a straight line, but when I look at work that I’ve done, it’s the ones that aren’t so perfectly straight that I like most. Even though at the time, it seems like, “Oh no, I’m messing up!” Those pieces have a life…a feel that makes them more interesting for me, even though in the making it’s a challenge to allow myself to let go.

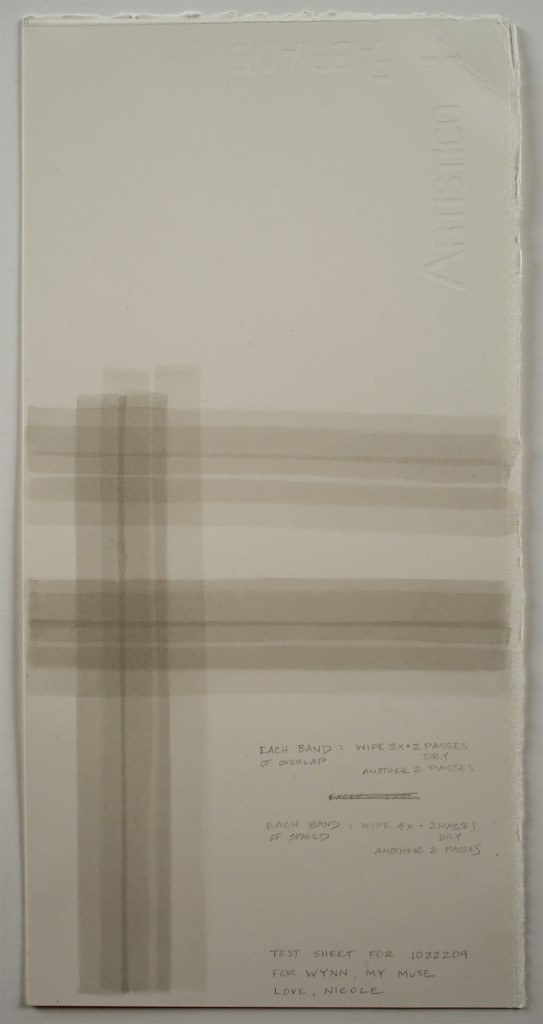

Figure 2. Nicole Phungrasamee Fein, Untitled (Test Sheet), 2009

Watercolor and graphite on paper, 14 3/4 x 14 3/4 inches (37.5 x 37.5 cm)

© 2012 Nicole Phungrasamee Fein

The untitled test sheet from 2009 (fig. 2) is very special because it captures one of those magical moments in the studio of discovering something unexpected. On a test sheet, I’m testing color, but I’m also testing line, figuring out how many passes I need to make in order to achieve the effect I want. Here I wasn’t paying close attention to how I laid down the lines; they overlapped, and I suddenly saw two different patterns coming together. Before that moment, it had never occurred to me to put one pattern on top of another. That idea opened up a whole new world of possibilities. The results were always surprising—more interesting than anything I could have deliberately planned. For the first time in my work, there was movement and rhythm. Before, everything had been very still.

I used the same idea to make 1042809, also from 2009 (fig. 1). In this drawing, the overlapping patterns ended up creating a central square, which was very exciting. I didn’t know that would happen when I was making the test sheet; as I was drawing, I could see it emerging.

RN: How many studies do you make before you begin working on a finished drawing?

NF: It’s usually one or two.

RN: Do you sit down to make a study with the idea that you’re going to make a specific drawing based on that study?

NF: Yes. But again they’re very sketchy. I don’t know what the drawing is really going to be like, even though I’ve figured out the spacing and the overlapping on the test sheet. I still don’t know what the final outcome will be.

RN: Once you’ve made a study, do you keep it by you while you’re making the drawing?

Figure 3. Nicole Phungrasamee Fein, Untitled (Test Sheet), 2009

Watercolor on paper, 15 x 7 3/8 inches (38.1 x 18.7 cm)

© 2012 Nicole Phungrasamee Fein

NF: I make a test sheet to understand the patterns I want to use, and then I use those studies to apply guiding marks to the larger drawing paper. Those marks are removed once the work is complete. But I don’t refer directly to the study once I’ve started working. At that point, my total focus is on the line of the moment.

RN: Is the pattern that you devise before making each drawing a way of being decisive in advance, so that then you can be focused without having to make decisions?

NF: Yes.

RN: What do you find challenging about making these drawings?

NF: There’s really no room for error in my process, so a good drawing is rare. I have to try not to get discouraged, because so many of them don’t come out right. I just have to start over.

RN: It’s an apt metaphor for daily life.

NF: Yes, that’s true.

RN: Can you tell us about how you came up with the idea for Coriolis (2010; fig. 4)?

NF: Yes, I would love to tell you. Because there were so many woven patterns in the watercolors I was making around that time, I started thinking about textiles and decided to learn how to sew. One day I went to the fabric store with a tunic that I wanted to copy. The woman there gave me what she said was patternmaking material, and I spent that weekend on my hands and knees in the studio, trying to draw a pattern. The patternmaking material was covered in red dots—a dot matrix. I was surrounded by dots, and the material was semitransparent, so the dots were coming in and out and all around me…. I quickly lost interest in the idea of trying to make something to wear. I thought: “This is great material. I should do something with this.” I started to play with layering it. I thought: “This is preprinted material! It’ll save so much time.” Well, I quickly realized that it’s mass-produced, so the dots aren’t printed perfectly.

WHK: The register is bad.

NF: The register is bad, and in order to align them on top of each other…it just wasn’t going to work. I realized I would have to draw all my own dots. [Sigh.] Which is of course so much more true to my nature and way of doing things. I started searching for the right material to use, and as has happened countless times over the years, Ed Green arrived at my studio with a roll of Holotex, which is a polyester material. Ed also made me some wooden drawing tools, which I used to stamp the ink onto the Holotex. I would apply color to the tool and then stamp it down to make each dot.

I started to play with the arrangement of the Holotex sheets, and I kept thinking, “How am I going to hold these sheets together?” I wanted to stick them together, but I didn’t want the adhesive to show. I realized that I had only the space of the dots under which to hide adhesive, so I made a double-sided tape dot for every single drawn dot, using a Japanese screw punch.

Play to hear Nicole Phungrasamee Fein speaking about the discovery of her work Coriolis.

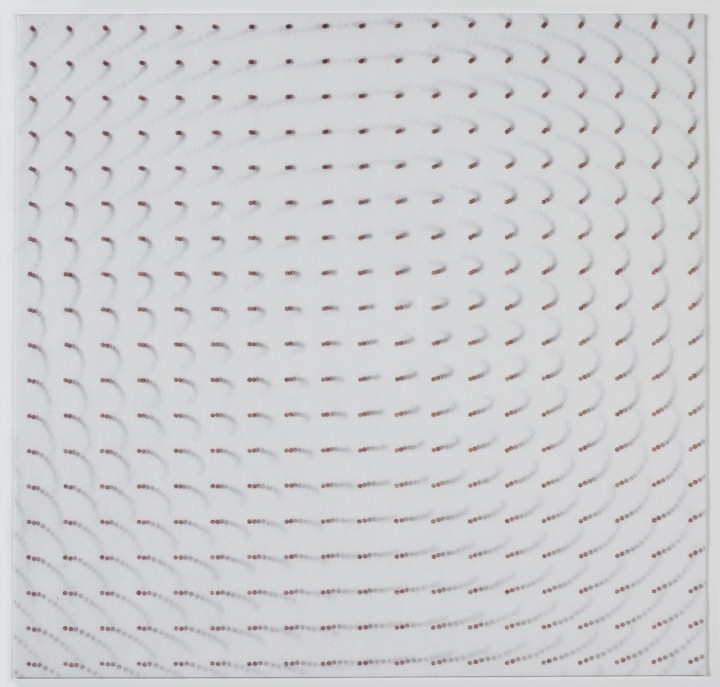

Figure 4. Nicole Phungrasamee Fein, Coriolis, 2010

Ink and tape on polyester, 18 3/4 x 18 3/4 inches (47.6 x 47.6 cm) © 2012 Nicole Phungrasamee Fein

The original idea for Coriolis was that the dots would rotate around the center. That was what I wanted to see happen. I had arrayed all of my sheets after months of preparation, with the dots and all the tape on them. One day, when I thought I was ready to remove the release paper from the double-stick tape and actually adhere all of it, I started to move the stack, and the sheets slipped from my fingers. They arrayed themselves into Coriolis by chance. I was stunned—in awe and just silent. I couldn’t move. I stood there looking at this pattern; I didn’t know what it was, and I didn’t understand it.

I quietly tiptoed upstairs and whispered to Mark and [my son,] Felix: “Something just happened in the studio. You have to come and see.” We looked at it together, and we didn’t understand what it was, but it was far more interesting than what I had been planning to do. For days, I stood and looked at it. I studied it and tried to figure it out, tried to understand it enough to intentionally do it. Yet I only had those sheets prepared to work with, so one by one, I started removing them to remake Coriolis.

WHK: That’s amazing, because you probably had a fairly square original pattern for it.

NF: Yes, my plan was perfectly symmetrical and very predictable. In Coriolis, there’s no center of gravity. There’s no single point around which the dots rotate. Some recede and some come forward.

RN: They array themselves within a very three-dimensional space.

NF: Yes.

RN: There’s a meditative and infinite feeling to looking down into Coriolis that references, in a lot of ways, your watercolors—but in a more dimensional way.

NF: Yes, within a deeper space…

RN: Is your work a sort of diaristic exercise?

NF: Yes, it is. The title of each work is the date of its completion—just a way of marking for myself at what point in my life I made each one.

While the test sheets are notations for formal drawings, all the works are notations for my life. The finished works show something about my state of being on a particular day; the individual lines record the moments.

RN: Do you find that there’s a correlation between the drawings that you consider failed and a certain way that you feel?

NF: Yes, I think so. It depends on why a drawing has failed, but oftentimes it’s because I wasn’t feeling steady or able to focus enough—or to slow down enough.

RN: Are you trying to slow your life down enough to make each drawing, or do you make each drawing because you want to slow down?

NF: I draw in order to slow myself down. The practice of drawing keeps me centered. We have gotten very busy, and I hope that I can bring a sense of slowing down to other areas of my life. I feel like the world we live in right now moves so quickly, and there are so many different directions to go in every day. I am truly blessed that my life is filled with a loving family, dear friends, and lots of fun, but I do treasure my studio time. My goal is to be present and attuned to whomever I am with and whatever I am doing.

RN: Is there something about drawing daily that helps you?

NF: Drawing is always better when it’s a daily practice. I take any window of time that I can. That time becomes sacred. The rituals of the practice help to quiet my mind.

I’ve found that when drawing is a daily practice I have a good rhythm that creates a momentum. The work develops and evolves much more readily than it does if I’ve taken a break. But when I do take time off, I return with a greater appreciation for the practice. I see the work with fresh eyes. This new perspective brings a welcome shift.

RN: Do you have a sense of how the patterns you make have evolved from earlier pieces to the present?

NF: The very first patterns were the simplest, the most basic: one line touched the next line, and a field was made out of these lines touching. One day, I turned the paper ninety degrees and crossed over those lines, and a grid appeared. Every drawing since then has been another iteration, a variation on that idea: changing the spacing of the overlapping, changing the width of the line…. Each one comes after the next. I’ll see something happen in one drawing, and it’ll spark something I use in the next.

RN: The patterns you develop are based on things you observe while making your drawings?

NF: Yes, and while working things out on the test sheets. One drawing leads to the next as a natural progression.

RN: Where do you see these patterns going, or do you feel that they have fully arrived?

NF: Every time I feel that I’ve arrived, they evolve. Something shifts that takes me in a new direction. But at the same time, I feel like I’m doing the exact same thing I’ve always done—and that is one line after another.

I do keep coming back to the simplest drawings, in which each line touches the edge of the previous line. Those drawings keep me grounded. They are the essence of my practice. So perhaps the very first one had fully arrived.

Play to hear Nicole Phungrasamee Fein speaking about the “slowness” of her process in conversation with Wynn Kramarsky.

Notes

Nicole Phungrasamee Fein

Wynn Kramarsky

Rachel Nackman

Frank Badur in Conversation

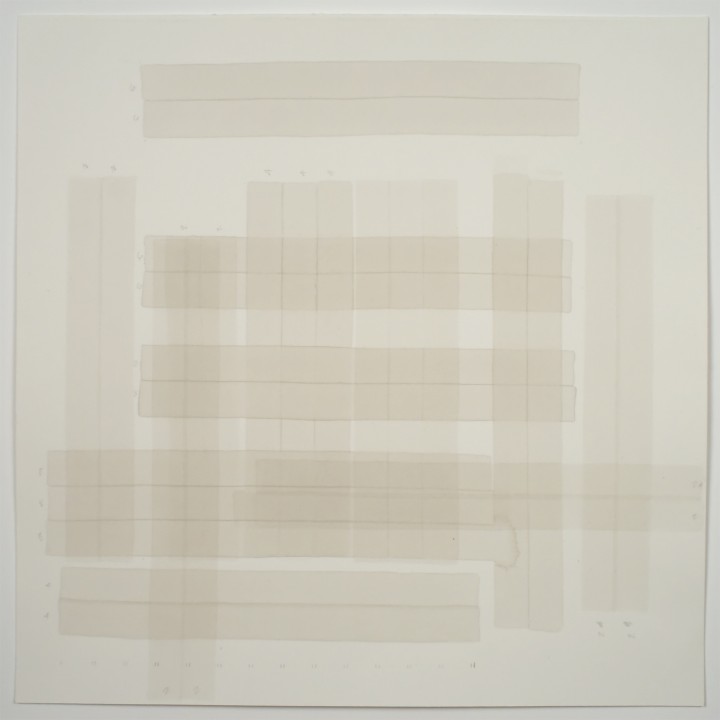

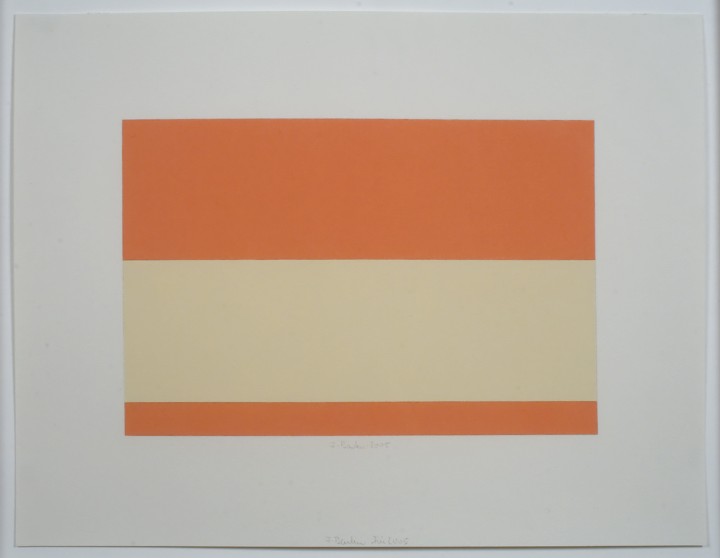

Figure 1. Frank Badur, Untitled (Fin), 2010

Gouache and graphite on paper, 14 1/4 x 18 inches (36.2 x 45.7 cm)

© 2012 Frank Badur

Frank Badur

In Conversation with Wynn Kramarsky & Rachel Nackman

August 2012

Frank Badur: The process of making a drawing begins with an impulse. Very often my drawings stem from my interest in architecture or in nature. I may also be thinking about music, Asian philosophy, or Asian poetry. But—and this is important—my work is never narrative; those sources provide only the impulse to start my drawings.

I don’t follow any system. The process of making a drawing, for me, is not systematic. If I’m in my studio and I’m absorbed in making a drawing, then the drawing tells me what my hand has to do next. The only things that are predetermined about each drawing are the measurements of the support and its orientation. Often the drawing starts with a very simple grid, and then I start to form my idea. The process develops more or less intuitively.

Like the Taoist yin and yang, my freehand irregular graphite grids provide a complementary contrast to the very precise work I do with gouache and a ruler. I like this contrast. I see the irregular grids as diagrams of my awareness as I go through the process of drawing. It’s very interesting for me to look at a drawing and to see how engaged I was, or how anxious, or how quiet my environment was.

Rachel Nackman: The freehand irregular grids can be read as a record of your mental state while making the drawing?

FB: Absolutely. Color is also an extremely emotional medium, and for me it too creates a very specific atmosphere. If you look at my drawings, I think you can observe all kinds of different color atmospheres. I have a huge color memory from my travels—you could call it a virtual color library. This is what I use in my studio.

For example, when I was in Kyoto, I was absolutely overwhelmed by the Katsura Imperial Village—by the balance of symmetry and asymmetry in the architecture, by the use of very pale colors. Years later I remembered what I had seen there, and it influenced a whole group of drawings. However, the reference is never direct; color is just something that comes back to me, and then I use it.

Wynn Kramarsky: You’re saying that your drawings are not reproductions of things you’ve seen in your travels, but they’re records of your emotional responses.

FB: Right. That’s also how I came to understand Agnes Martin’s paintings. I was in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and I thought: “Wow! These horizontal layers of light, of desert, of color—that’s what I see in the paintings of Agnes Martin.” Her work is not narrative or directly referential, but I think that she was attuned to color impulse.

RN: The impulse or the emotional response that you have to your environment then allows you to make color choices in your drawings, as well as choices about the type of line you’ll apply or about the type of grid you’ll apply?

FB: Yes. Each drawing starts out very simple, and then it becomes more and more complex. Very often I’m surprised when the drawing is finished. Sometimes I’m happy, and I can agree with my drawing. But sometimes I have to go back into it.

RN: When you have a final result that doesn’t please you or that doesn’t fit with what you were interested in achieving, you go back and rework things?

FB: Absolutely. Or I throw it into the garbage. [Laughter.] Sometimes when I make one drawing, I get the idea for the next drawing. If I’m very satisfied, then I may have the impulse to do another drawing—a third or a fourth drawing. The whole complex of my drawings grows when I’m working in my studio.

Figure 2. Frank Badur, Untitled (Fin), 2005

Gouache and graphite on paper, 13 3/8 x 17 3/16 inches (34 x 43.7 cm)

© 2012 Frank Badur

RN: Can you then look back at a body of work from a certain period and read a certain linear progression in the drawings that you made during that time?

FB: Yes. I can see my passing interests or my notions about other artists’ works. I can read all of this.

WHK: You first came to the United States in the early 1980s, and you’ve said that your exposure to contemporary American art at that time was eye-opening. Were you also exposed to Native American artwork while visiting the States?

FB: Yes. After my first trip to the United States in 1982, I returned many times to visit the Southwest. I went hiking with the Navajo Indians, and I learned about Navajo, Hopi, and Pueblo culture. Many of the Pueblo were potters, and I was utterly fascinated by the patterned drawings they made on their pottery. They are highly abstract, and they also have no system—it comes from the inside out. When I asked one of the oldest Pueblo potters how she made these drawings, she told me: “I don’t know. I think I get it from my ancestors, and I can do this only if I find a balance in my family and balance in nature. Only then am I able to do it.” I understood this so easily and so deeply.

RN: You found in studying Pueblo pottery that abstract pattern itself was evocative and that the artist was acting almost as a medium to deliver that pattern?

FB: Yes, absolutely. Each piece of pottery is almost like a piece of sculpture—the artist builds up the clay and smoothens the outside of the object by hand so that he or she can apply the drawing to its surface. They’re very involved with the pieces they create.

RN: What they do is develop a relationship with the support.

FB: Yes.

WHK: Occasionally you’ve used special handmade paper. Do you choose that support because you specifically want to make a drawing on handmade paper, or do you do so just because you have handmade paper available?

FB: I don’t just use the paper that’s available. I choose whatever is the right material for my technique.

RN: Can you tell us about the different mediums you use in your drawings?

FB: When I choose a medium, it’s also in order to engage with the specific characteristics of that medium. For example, if I make a woodblock print or an etching, I am working with those techniques in order to achieve a particular visual result, which I cannot find in another medium.

RN: Are your drawings then celebrations of these various mediums?

FB: Absolutely. I always have an idea of what I want to do, and to come close to the idea, maybe I need a brush and paint, or I need a pencil, or I need to make an etching or an aquatint. So the result is what leads me to the medium.

RN: The drawings on view here are made with gouache and graphite. Can you tell us what it is about gouache and graphite that attracts you?

FB: Yes, of course. Gouache is wet, and graphite is dry. To apply gouache, I use the brush; for graphite, I use my pencil. So the mediums and tools are soft and hard. These are opposite principles, like yin and yang. I like this—hard and soft, wet and dry. It’s a wonderful way to work.

RN: Can you tell us what it’s like to make these drawings?

FB: Making a drawing is usually a very slow process. Very often I work on four or five drawings simultaneously, so if one drawing needs time to dry, I focus on another drawing. It’s almost like a family—you have to figure out which child needs a little bit more attention than the others.

I think the aura of a work on paper is different from a painting on canvas. For me, drawing is very intimate, and painting is something you can feel or measure with your body. A work on paper is really in your hand: you measure it with your hand, and you hold your tool in your hand. Painting is very physical and requires a lot of distance from the canvas. With a drawing, I have a piece of paper in front of me, and I’m completely by myself and absorbed by the work. I’m in a contemplative state for hours.

Sometimes when I finish something, I realize I’m hungry and look at my watch—only to see that four or five hours are completely gone. Sometimes I have to ask myself: “How did this happen? And who made this drawing?”

RN: As you’ve said, you sometimes feel surprised by what you see.

FB: Yes. It’s almost like an adventure tour. I have an idea, and I try to come close to it. But sometimes I open a new door, a new space, and I have the freedom to make something else instead.

Bios

Frank Badur

Wynn Kramarsky

Rachel Nackman