Amanda Beresford on Sol LeWitt

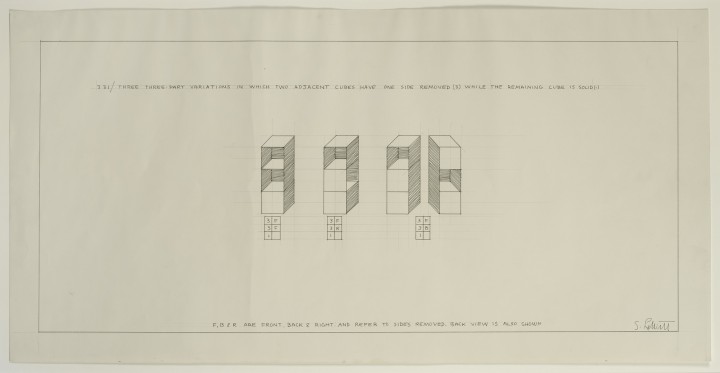

Figure 1. Sol LeWitt, Three-Part Variations on Three Different Kinds of Cubes 331, 1967

Ink and graphite on paper, 11 3/4 x 23 3/4 inches (29.8 x 60.3 cm)

© 2012 The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Sol LeWitt

by Amanda Beresford

In his 1967 essay “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” Sol LeWitt insisted on the primacy of the idea in the mind of the artist over the final artwork to which it led. The concept, he wrote, is the most important thing about the work; it is “the machine that makes the art.”1 Following LeWitt’s logic, any drawing or diagram produced by the artist is to be regarded as part of his thought process and thus occupies a privileged position in his oeuvre as a record of the artist’s ideas.

Three-Part Variations on Three Different Kinds of Cubes 331 (1967; fig. 1) is one of a series of drawings consisting of variations on three stacks of three cubes. Each drawing contains two lines of explanatory text and three box diagrams, which explain the system employed for each cube stack according to a coded alphanumeric key.2 This drawing is headed with a handwritten notation describing the system employed: “3 3 1 / THREE THREE-PART VARIATIONS IN WHICH TWO ADJACENT CUBES HAVE ONE SIDE REMOVED (3) WHILE THE REMAINING CUBE IS SOLID (1).” The structures are drawn in a precise, impersonal style, entirely uninflected by expressive intent. The strict perspectival rendering makes clear that these are three-dimensional objects translated onto a flat surface; a pale grid of ruled lines defines their edges and corners, articulates their uniform dimensions, and emphasizes the two-dimensionality of the paper, generating a geometric tension between actual flatness and implied depth. The text at the lower edge of the sheet explains the symbols in the key boxes below the cube stacks. LeWitt’s drawing and its rubric are clear and direct, claiming to be exactly what we see and no more. The artist lays bare the parameters of his system, and it is up to us to make what we will of it. The drawing functions, as LeWitt wrote, as “a conductor from the artist’s mind to the viewer’s”; its meaning as a study for sculpture is perhaps subsidiary to its role as an intellectual exercise for the artist.3

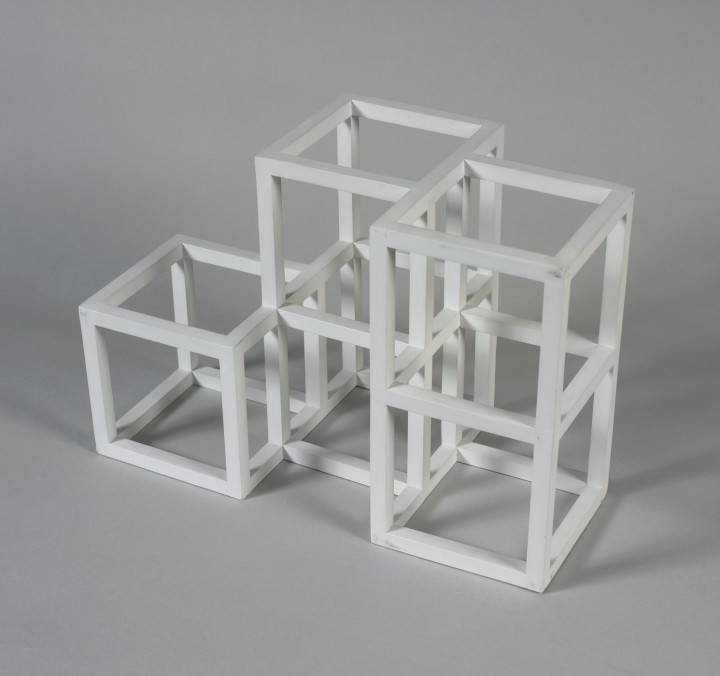

Figure 2. Sol LeWitt, Maquette for 1 x 2 x 2 Half Off, 1990

Paint on wood, 10 x 14 3/4 x 7 3/4 inches (25.4 x 37.5 x 19.7 cm)

© 2012 The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

LeWitt made a great many drawings as plans for three-dimensional structures based on incomplete open cubes; beginning in the late 1960s, he also made maquettes, such as Maquette for 1-2-2 Half Off (1990; fig. 2). This small-scale painted wood construction of five asymmetrically conjoined skeletal cubic modules, from which LeWitt “removed the skin,” reveals another variation on the realization of his system, emphasizing the artist’s foundational idea that the work of art can be realized in several ways—as drawing, as sculpture, or solely as concept, remaining in the mind of the artist.4 The stark simplicity of LeWitt’s sculptures and drawings was vital, he felt, since complex forms “would be too interesting” and might “obstruct the meaning of the whole.”5 He chose the cube as his base unit owing to its neutrality as well as to its simplicity. It is, he claimed, “relatively uninteresting,” lacking any emotive force, and has the advantage of being “immediately understood” as “uncontestably itself.”6 The cube functioned as a tabula rasa for the elaboration of the artist’s thought process, which in turn became the subject matter of his work. Like other Conceptual artists, LeWitt used language as a metaphor for this process: he spoke of the cube as both the “grammar” and the “syntax” of the total work—literally the elemental building block from which limitless variants could be constructed.7

Paradoxically, LeWitt stressed that his serial approach should not be regarded as rational, despite the formal logic of its visible expression: “Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists. . . . Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically.”8 Both the incompleteness of his cubes and their apparently endless permutations have been read as signs of the deliberate—even parodic—irrationality of his systems, notably by Rosalind Krauss, who believed, as Nicholas Baume has remarked, that LeWitt demonstrated a worldview that was “skeptical of any claims to universal truths.”9 Readings such as this—alongside John J. Curley’s claim that the cubes’ incompletion signals, among other things, “the inability of scientific thought to restore wholeness to society”—imply that LeWitt may have knowingly played with the relationship between the rational and the irrational as a form of social commentary.10 His drawings and sculptures suggest a process of endless serial production that remains incomplete, even futile, for all that LeWitt continued to make them.

Notes

1. Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” in Sol LeWitt: Critical Texts, ed. Adachiara Zevi (Rome: Libri de AEIUO, 1995), 78.

2. The drawing relates to an artist’s book by LeWitt: 49 three-part variations using three different kinds of cubes / 1967–68 (Zurich: Bruno Bischofberger, 1969). The book contains the prints 3-3-1 and 3-1-3, which are identical to two drawings in the Kramarsky collection: Three-Part Variations on Three Different Kinds of Cubes 331 (1967) and Three-Part Variations on Three Different Kinds of Cubes 313 (1968).

3. Sol LeWitt, “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” in Zevi, Sol LeWitt, 89.

4. Josef Helfenstein, “Concept, Process, Dematerialization,” in Drawings of Choice from a New York Collection, ed. Josef Helfenstein and Jonathan Fineberg (Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2002), 14.

5. Sol LeWitt, “Serial Project No. 1 (ABCD),” in Zevi, Sol LeWitt, 76.

6. Sol LeWitt, “The Cube,” ibid., 72.

7. LeWitt, “Serial Project No. 1,” 76, 75.

8. LeWitt, “Sentences,” 88.

9. Nicholas Baume, “The Music of Forgetting,” in Sol LeWitt: Incomplete Open Cubes, ed. Nicholas Baume (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 21.

10. John J. Curley, “Pure Art, Pure Science: The Politics of Serial Drawings in the 1960s,” in Infinite Possibilities: Serial Imagery in Twentieth-Century Drawings (Wellesley, MA: Davis Museum and Cultural Center, 2004), 33. Sarah Louise Eckhardt observes that the cubes’ potential for variation reveals the subjective arbitrariness of LeWitt’s decisions, subverting his systems’ apparent order. Sarah Louise Eckhardt, “Sol LeWitt,” in Helfenstein and Fineberg, Drawings of Choice, 82.

Bios

Amanda Beresford

Sol LeWitt