Elissa Weichbrodt on Robert Grosvenor

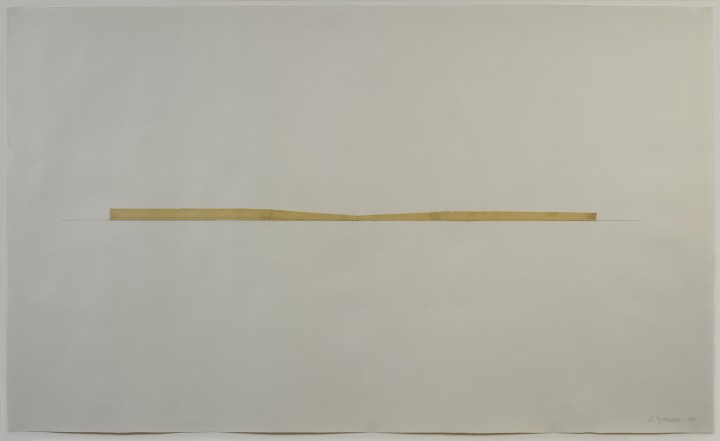

Figure 1. Robert Grosvenor, Untitled, 1974

Masking tape and graphite on paper, 29 1/2 x 49 1/4 inches (74.9 x 125.1 cm)

© 2012 Robert Grosvenor.

Robert Grosvenor

by Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt

A crisp horizontal line, drawn in pencil, floats precisely in the middle of an expanse of creamy paper. Laid parallel to and just barely touching the graphite line is a long length of yellowed masking tape that dips slightly in the middle. Spare but not clinical, the drawing evinces a sense of fragile balance. Although the tape appears to be a single strip, it actually consists of four smaller pieces; the translucence of the tape allows us to see the delicate tears where the bits overlap, creating a kind of rhythm. The subtle excavation of the central section of tape offers a moment of visual pause, which is in turn counterweighted by the darkening of the pencil line toward the ends of the tape.

This untitled drawing by Robert Grosvenor (fig. 1) is related to a series of projected sculptures consisting of timber beams placed on gallery floors or set into the earth.1 The artist often used drawing as a means of working out the structural principles of his proposed outdoor sculptures. Grosvenor described his creation of such large-scale projects as a calculated process: he would first make a central cut in a large wooden pole, excavate dirt from below the cut, and then carefully apply pressure to the center of the beam using heavy construction equipment, causing its middle section to break and sink slightly into the ground, out of view.2 In the drawing, the pencil mark designates the earth, and the sloping masking tape represents the broken beam being pushed below the ground line.

Figure 2. Robert Grosvenor, Untitled, 1973

Wood, 20 3/4 x 5/8 inches (52.7 x 1.6 cm)

© 2012 Robert Grosvenor.

This kind of large-scale sculpture was typical of Grosvenor’s practice in the early 1970s, when he abandoned monumental, gravity-defying geometric forms for timbers and wooden poles that emphasize gravitational effects. Another piece by Grosvenor in this exhibition demonstrates a scaled-down version of this approach. The untitled sculptural work (fig. 2) consists of a wooden dowel just over twenty inches long and about half an inch in diameter. A web of fine cracks encircles the middle portion of the dowel, fracturing but never quite rupturing it altogether. Though they destroy the wood’s integrity, the delicate fissures also delineate its fundamental cellular structure. Grosvenor called the resulting breaks “drawings.”3 Such a designation emphasizes the linear, surface quality of the cracks across and around the wooden beams.

Together, the splintered dowel and the masking-tape drawing offer valuable insight into Grosvenor’s process. While we might be tempted to equate the breakage of the wooden poles or timbers with a kind of impulsive, expressive violence, these preliminary studies suggest instead a degree of purposeful calculation and nuance. The delicate mesh of splinters that holds together the slender wooden stick was produced through the restrained application of pressure rather than the forceful swing of a hammer. And the plotted rupture and points of compression in the drawing, expressed by the darkened pencil line and carefully torn pieces of tape, similarly reflect the thoughtfulness of Grosvenor’s approach. The artist’s preparatory drawing and sculptural maquette attest to the fact that the larger sculptures to which they relate were created through the application not of aggressive force but of continuous, unyielding pressure, with the accumulation of stress inevitably resulting in a dispersal of energy.

Notes

1. Christine Mehring, “Robert Grosvenor,” in Drawing Is Another Kind of Language: Recent American Drawings from a New York Private Collection, by Pamela M. Lee and Christine Mehring (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 1997), 58.

2. Jordana E. Moore, “Robert Grosvenor,” in Drawings of Choice from a New York Collection, ed. Josef Helfenstein and Jonathan Fineberg (Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2002), 56.

3. Robert Grosvenor, quoted in Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe, “Robert Grosvenor: Specific Clarity,” Art in America 64 (March–April 1976): 84.

Bios

Robert Grosvenor

Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt