Teo González in Conversation

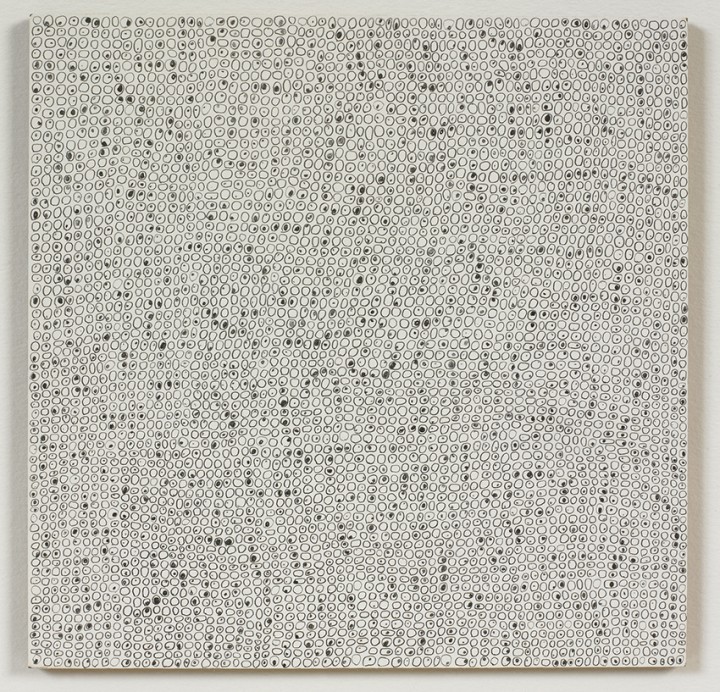

Figure 1. Teo González, Drawing 230, 2008

Graphite on clay board, 5 x 5 inches (12.7 x 12.7 cm)

© 2012 Teo González

Teo González

In Conversation with Rachel Nackman

March 2012, New York

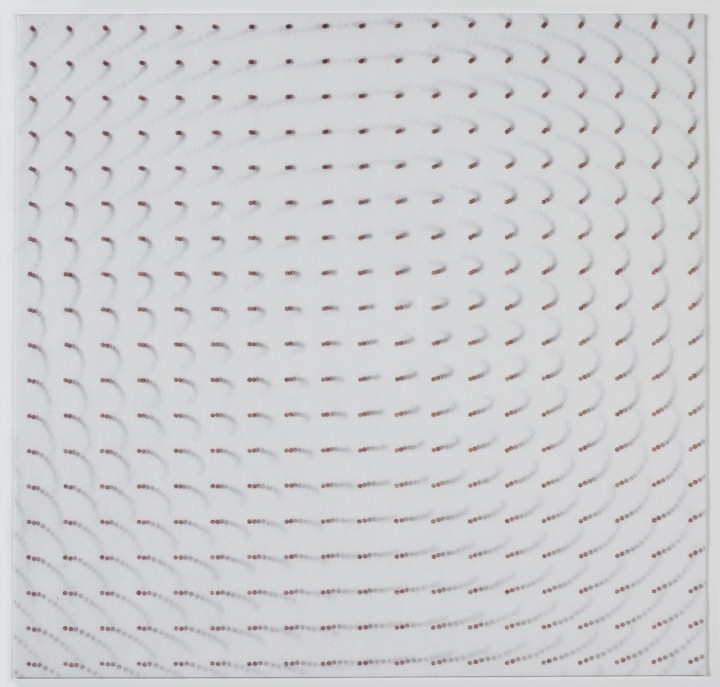

Rachel Nackman: Can you tell us a little bit about the process of making Drawing 230 (2008; fig. 1)?

Teo González: First, I thought about I wanted to do and gathered the materials I would need. I made a grid of circles, using some of them as markers to divide the square of the piece into smaller squares. Then I repeated that process across the entire surface, until the piece looked like a chessboard, with rows of alternating circles and empty spaces. I filled those empty spaces with more circles, and then I filled all the circles with dots.

I’ve used clay board for years now, and I’ve used pencils for as long as I can remember. I selected those materials to make this piece for their simplicity. I knew that this piece was going to be an oddity when I made it, because rather than composing an image by arranging thousands of drops and letting them dry out, as I usually did, I decided that I was going to draw them. It felt natural to choose something as basic as pencil and paper because I was starting something new.

RN: Was this one of the first drawings that you made by drawing the circles?

TG: It was only the second one that I made as an attempt to do a final piece. But I had also made some tests, just to see how it would work out.

RN: Can you tell us a little bit about the way you made work before trying this new technique?

TG: I would start by preparing the surface of the painting. Working with the support flat on a table, I would dissolve a little bit of acrylic enamel in water, and I would make a wash. Then I would apply drops of the wash to the surface with a paintbrush, and I would let each drop start to dry out. Before they were completely dry, I would put a smaller drop of undiluted acrylic enamel into the center of each drop, where a little bit of water remained. Then I would let the work dry completely. I wouldn’t stop until I filled the last spaces with these dots—then I was done.

RN: Were you mindful of the time it was going to take to finish each work?

TG: Well, there was no way to know how much time each work was going to take. I was always surprised by how much the end result would change depending on the weather. If the room in which I was working was very dry, the drops would dry faster—and vice versa. The funny thing is that once the drops started drying, all of them would dry at once. So the beginning of the process was slow, but as the drops started drying, there would come a moment when I lost control over what I was doing. I actually wouldn’t have time to think about what I was doing—I would be trying to tackle the piece at that point.

RN: Like a physical challenge.

TG: It was like a physical challenge, yes. That’s part of the process that I really haven’t missed since switching to drawing the drops. With the liquid medium, I felt like the outcome didn’t depend on me. I was just mediating—making sure that the thing got finished. I didn’t have all that much control. It was frustrating.

RN: Was that dependence upon external factors—the environment and time—one of the reasons why you started thinking about drawing the dots?

TG: Yes, definitely. Another important factor was that the original process limited the maximum size of the drops, which in turn meant that the size of the overall painting was also limited. If I draw the drops, I can draw them whatever size I want. I guess the decision was partially about environmental factors and partially about wanting to be able to play with scale.

RN: In both senses, what you were really trying to do was maintain control.

TG: Yes. I don’t think that there is too much intuition in my work. At the beginning there was, because I was exploring. In the final work, though, I want it to look good. Having completed the process as many times as I have, I’ve learned what can happen.

RN: So you feel very comfortable with your process now?

TG: I feel almost overconfident now. I started making the drops with paint in 1991. At the first exhibition I had of these works, someone asked me, “What are you going to do after this?” I said, “ . . . More of this?” Obviously. I kept on going, but I never knew where I was headed. I was amazed when years started passing and I still wasn’t at the end of this exploration. There was something that was keeping me going.

The first time I drew the drops was in 2007, and this drawing is from 2008. So sixteen years after I’d started working with drops, I suddenly found myself at the beginning again.

RN: Did you see the transition from making drops with enamel to drawing the dots by hand as the culmination of those sixteen years of working with paint?

TG: It was definitely a transition. I’m not renouncing the painted drops; I see them as included in what I’m doing now. Except instead of allowing the process to be the protagonist, now I’m stepping on the stage to some extent. I still draw the drops in much the same way that I painted them.

RN: To your hand it feels very similar.

TG: Yes, it’s almost exactly the same thing.

RN: How did you begin making the drops?

TG: I started making this work as a reaction to what I was doing at the time. When I started painting, I tried to practice Abstract Expressionism. I loved it—I still do. But it was emotionally taxing work, and I kept falling into creative crises. I would lose track of what I was doing, whether or not I liked it anymore. I decided that if I wanted to keep on being an artist, I had to find a way to put some distance between the work and myself. Not literal distance but emotional distance.

I thought that by using a ruler and a pencil to make straight lines I could make my work become a little more impersonal. A straight line will be straight no matter who pushes the pencil. Then I thought about how naturally occurring processes—like what happens when I drop one fluid inside another—also behave independently of the artist. They’re also very impersonal.

The next step was putting it all together. That’s when I started doing the drops. I began by making freehand drawings of grids of dots—they were very loose. After that I tried drawing a pencil grid on the paper with a ruler. Then I became really purist and decided that if the grid was going to be there, I might as well make it with ink. I’m not trying to hide anything over here. At the beginning I was only working with ink on paper. Next, I discovered how to work with acrylic on canvas. For some reason, it felt very strange to put pencil or pen to a painted surface in order to draw the grid, so I designed a series of contraptions that would float a gridded net of fishing line an inch above the canvas. Then I would use a paintbrush to put the drops into each of the open spaces of the net.

A few years after that, I finally felt confident enough to make pencil lines directly on the canvas. I actually liked doing this, but by then I had decided to start making the drops very small, and the little net no longer worked with a paintbrush. I decided I was going to draw a net directly on the surface of the canvas with a pencil instead. I drew it and liked it, so I kept on drawing the net. A little while after that, I started feeling that the grid for the drops was almost too tight. So I gradually widened the gauge of the net so that each opening in the grid could accommodate more and more drops.

The entire process was about the question, “What if?” What if I do this? Sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn’t. If it works, you’ve hit the jackpot.

RN: So reaching this point was a graduated process of learning?

TG: Very much so.

RN: Did it become a question of challenging yourself?

TG: Yes. What happens very often is that once you learn how to do something, your passion for making it lessens. So you try to change it little by little, because you want to enjoy the whole ride.

I think it took me from 1991 to 2002 to go through the development I described with the drops. I could have done it faster if I’d known exactly where I wanted to go, but I never decided ahead of time what I was going to do next. I always thought my plate was full with thinking about how I was going to get out of this mess now. That process of discovery was and is very appealing to me.

RN: What parameters do you set for a drawing before you begin making it?

TG: The parameters I set change from series to series, but there are two constants that I always choose between for each piece: there will be lots of drops—or in this case drawn circles—or they will be tiny. I decide what color and what materials I will use, and I decide upon the size of the drops. It’s very basic planning because my pieces are very simple. There is some planning to do, but not that much.

RN: Does that basic planning then free you to make decisions about other elements in the moment?

TG: Yes. For example, I decide where to put the inner dots once the surface of my drawing is covered with little open circles. Some people might think that it’s an intuitive kind of decision making, but I wouldn’t say it’s very intuitive, because I’ve already done this several hundred times. I know what works and what doesn’t.

RN: When you’re making decisions about where to place dots inside circles, what are you trying to achieve?

TG: I’m trying to make an image that doesn’t attract your attention to any particular part of it. In that sense, I’m in a color field mode (so to speak), even if there is no color. I try to create an image that is more or less consistent.

RN: In this particular drawing, your mark making extends to the edges of the sheet, but in some other works small images are centered on larger sheets. How do you make decisions about that?

TG: I make two types of compositions: overall pieces and Seagram pieces. This is an overall piece, in which the drops extend to the edge of the sheet—the focus is on the image that I’ve made.

I named the Seagram pieces after Mies van der Rohe’s building in New York City, because of the open square that he left in front of the tower. I think that square changes the way we see the building, and I thought it was a very bold move for Mies to leave so much of the space he’d been given undeveloped—and that on Park Avenue.

I felt that leaving empty space around the drawn grid changes the piece into a quasi-object. That space makes the drawing behave in a completely different way from the overall pieces. Overall pieces are very direct, whereas the Seagram pieces provide several possibilities for how one can start looking at the piece. I try to give the viewer a choice.

RN: What is it like for you to make a piece like this? How much time and focus does it require?

TG: People always ask how long it takes. I used to answer that I make these drawings in my spare time, but I’m unemployed, so I have plenty of it. [Laughter.] I actually don’t know how long one drawing takes. I’ve never worried about how long it takes, because I don’t think that’s the idea that interests me. If I stopped to think about how long it’s going to take, many times I probably wouldn’t do it. I’m not a patient kind of person, but I’m very curious. For me, curiosity is the driving force. Once I have an idea, I must see it done; that’s what keeps me going.

RN: You’ve said that you enjoy the process of making these drawings.

TG: Well, yes. When you have an idea that you want to see completed, it’s enjoyable to see it coming out well, of course.

RN: Do you ever consider something a failure?

TG: Yes. It’s a failure when the end result strays from my original idea. And then I put it in the trashcan. There’s no point in keeping it.

RN: You’ve said before that you choose to make work that speaks to the widest audience, without the burden of language or culture. What is it about the serial nature of your process that you think is universal?

TG: Well, to me it’s more of a process of elimination. I might not defend the idea that the type of work I do is universal (although I sort of do think so), but I do think that other kinds of work are not universal—either the viewers know the language or they’re left out. In that sense, my work is very basic. I don’t intend to make something that everybody can understand, but rather to reach as many people as I can. To some extent the type of work that I do can end up speaking for and about itself.

Bios

Teo González

Rachel Nackman

Nicole Phungrasamee Fein in Conversation

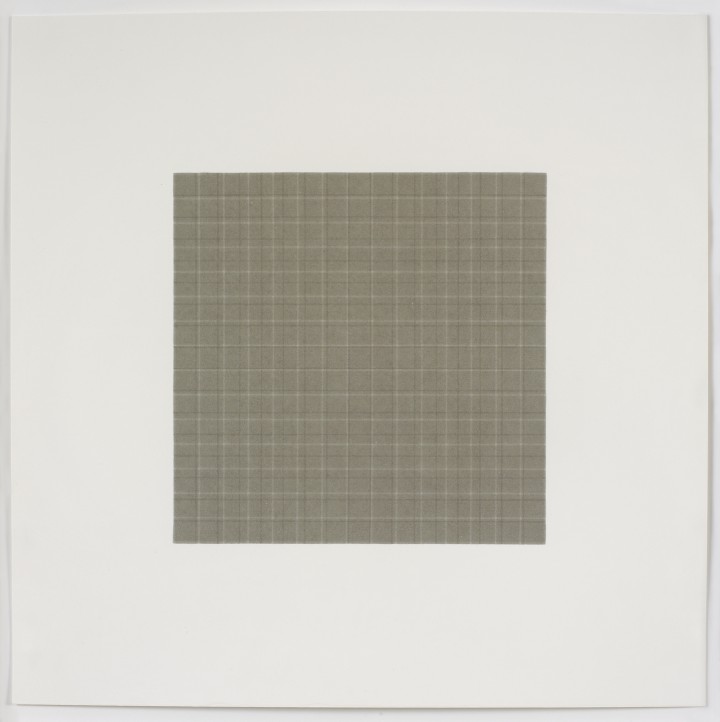

Figure 1. Nicole Phungrasamee Fein, #1042809, 2009

Watercolor on paper, 15 x 15 inches (38.1 x 38.1 cm)

© 2012 Nicole Phungrasamee Fein

Nicole Fein

In Conversation with Wynn Kramarsky & Rachel Nackman

March 2012, New York

Rachel Nackman: Can you tell us about the rhythm of making one of your drawings?

Nicole Fein: Slowing down is fundamental to what I do. I use processes that are technical, but the essence of the work is not the technique—it’s the process of slowing down and building something in a step-by-step, iterative manner. That is my approach to every day.

The slowing down comes from the very simple rituals of cutting the paper, setting it up, and doing tests on the test sheets. All those rituals bring me to a place from which I can make that first line.

Wynn Kramarsky: In making the initial decision to make a drawing, a particular drawing, do you think, “It’s nine o’clock on a Tuesday, and I have to make a drawing”? Or do you think, “I have to make a drawing, even though it’s nine o’clock on a Tuesday.” How disciplined are you? And how much of your work occurs because you suddenly feel that you must produce something?

NF: There’s a pressure that comes and goes—but it is like going to work. When it’s time to work, I am disciplined about bringing myself to that place.

WHK: Discipline of course can imply internal resistance. But you’re saying that your sense of discipline also makes you feel, “I must do this.”

NF: Yes, it’s both a discipline and a calling. Sometimes I can’t resist, like the times when I go downstairs to the studio—just to close up for the night—and something catches my eye, and before I know it, hours have passed and it is three in the morning.

RN: How long does it take you to make one of these drawings?

NF: The finished piece is ideally made in one sitting, but I make so many failed attempts that I don’t know whether to count those in the process of making one work—especially when I’ll complete one and it’s still not right.

RN: It could take anywhere from one sitting to several weeks of work to complete one drawing?

NF: Yes. And a sitting can last anywhere from a few hours to all day. The longest was fourteen hours straight.

RN: Can you tell us about the physical process of making each drawing?

NF: I can describe, first of all, the setup. My good friend Ed Green made me a beautiful large worktable. On the worktable is an adjustable easel. I used to draw bent over at a flat table, and it was really hard on my back and shoulders. I wanted to be upright. The easel that Ed designed allows me to turn the paper upside down to draw from both directions while also keeping the line I’m making at eye level. I start at the upper left-hand corner and move the brush from left to right, turn the board and the drawing upside down, and then go back over that line again, moving across the paper. A Velcro system allows me to adjust the height of the paper after every stroke. Through repetition, I get into a rhythm of drawing. But still, after many hours, standing or even sitting upright…I get tense and tired.

RN: Do you take breaks?

NF: I try not to take breaks. It’s best for the work that way. On a very intensive day, I won’t talk to anyone. I won’t eat very much. I try to avoid having to take a bathroom break. It’s rigorous.

RN: Do you have to prepare yourself in advance for that sort of endurance test?

NF: I don’t do anything specifically to prepare. I think it is different now than it was in the beginning, when I didn’t realize what would be required, and I would just get involved in a piece. Now that I know what it will take, it can be daunting, in the morning, to set out to do it, but…

RN: That’s when you approach the discipline that Wynn was talking about.

NF: Yes. Mentally it does require focus and patience, and I’ve often been asked whether it feels like a meditative process. I’ve never done strict meditation, but doing this kind of work requires absolute presence of mind, attention, and focus on the line at that moment. It does not leave me feeling refreshed at the end of the day. I feel completely depleted and exhausted. It’s not rejuvenating, as maybe meditation is.

One important thing to me, however, is that I do not want the drawings to feel labored over even though they are labored over. I want them to have a real sense of peace and calm, and I want them to simply appear on the paper.

WHK: When you finish a drawing and you decide, “Yes, this is a good one,” does that give you the kind of serenity that most of us experience when looking at your work?

NF: Sometimes it does, but sometimes it’s the opposite. I’ve completed a drawing and felt awful, like it’s just a disaster. This has happened a number of times, and I’ve come to bed in tears. And I wake up [my husband,] Mark, really upset, and he’ll have been rooting for me all day—hoping it goes well. I’ll tell him that the drawing is a failure. He’ll say, “Wait till tomorrow, wait till tomorrow, look at it again tomorrow.”

The next day it does look better, and the day after that it looks even better, and a week later maybe I can start to feel that sense of calm from it…. I’m learning to trust the process, to keep going even if it doesn’t seem like it’s going well. At its best, the practice brings calm.

RN: When you’re making a drawing, are you conscious of certain things that you need to do in order for it to turn out well?

NF: Absolutely. One of my long-running conflicts with myself is about trying to make a perfectly straight line. There’s some comfort in trying to maintain a straight line, but when I look at work that I’ve done, it’s the ones that aren’t so perfectly straight that I like most. Even though at the time, it seems like, “Oh no, I’m messing up!” Those pieces have a life…a feel that makes them more interesting for me, even though in the making it’s a challenge to allow myself to let go.

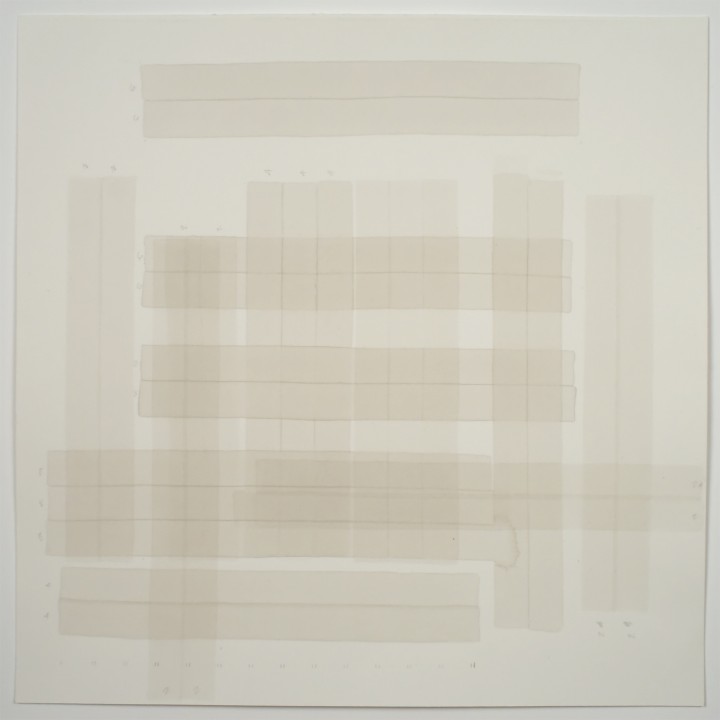

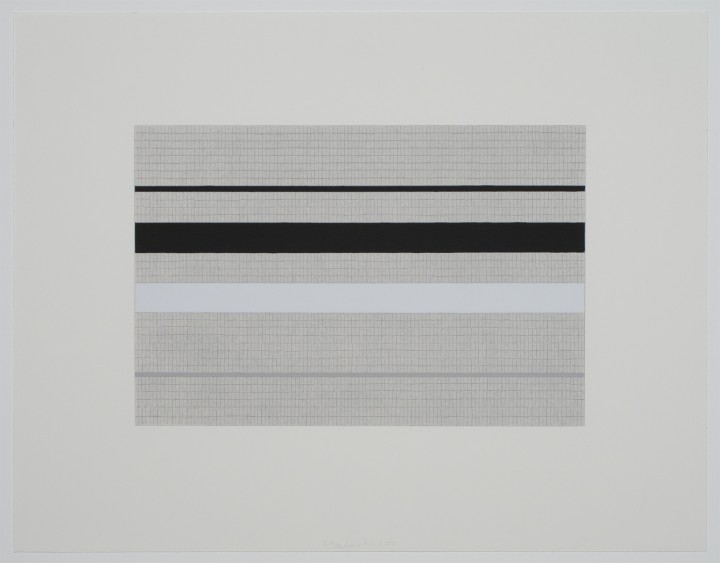

Figure 2. Nicole Phungrasamee Fein, Untitled (Test Sheet), 2009

Watercolor and graphite on paper, 14 3/4 x 14 3/4 inches (37.5 x 37.5 cm)

© 2012 Nicole Phungrasamee Fein

The untitled test sheet from 2009 (fig. 2) is very special because it captures one of those magical moments in the studio of discovering something unexpected. On a test sheet, I’m testing color, but I’m also testing line, figuring out how many passes I need to make in order to achieve the effect I want. Here I wasn’t paying close attention to how I laid down the lines; they overlapped, and I suddenly saw two different patterns coming together. Before that moment, it had never occurred to me to put one pattern on top of another. That idea opened up a whole new world of possibilities. The results were always surprising—more interesting than anything I could have deliberately planned. For the first time in my work, there was movement and rhythm. Before, everything had been very still.

I used the same idea to make 1042809, also from 2009 (fig. 1). In this drawing, the overlapping patterns ended up creating a central square, which was very exciting. I didn’t know that would happen when I was making the test sheet; as I was drawing, I could see it emerging.

RN: How many studies do you make before you begin working on a finished drawing?

NF: It’s usually one or two.

RN: Do you sit down to make a study with the idea that you’re going to make a specific drawing based on that study?

NF: Yes. But again they’re very sketchy. I don’t know what the drawing is really going to be like, even though I’ve figured out the spacing and the overlapping on the test sheet. I still don’t know what the final outcome will be.

RN: Once you’ve made a study, do you keep it by you while you’re making the drawing?

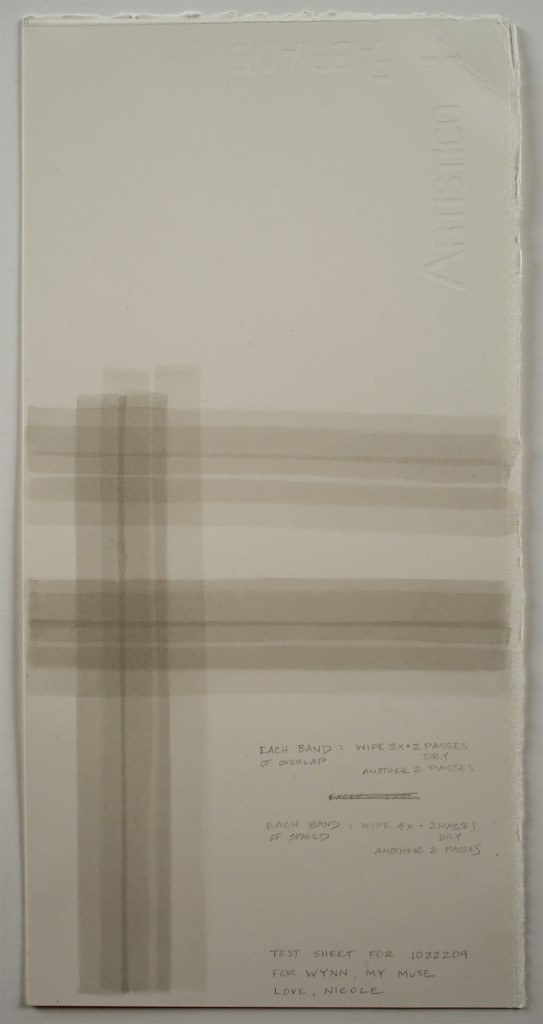

Figure 3. Nicole Phungrasamee Fein, Untitled (Test Sheet), 2009

Watercolor on paper, 15 x 7 3/8 inches (38.1 x 18.7 cm)

© 2012 Nicole Phungrasamee Fein

NF: I make a test sheet to understand the patterns I want to use, and then I use those studies to apply guiding marks to the larger drawing paper. Those marks are removed once the work is complete. But I don’t refer directly to the study once I’ve started working. At that point, my total focus is on the line of the moment.

RN: Is the pattern that you devise before making each drawing a way of being decisive in advance, so that then you can be focused without having to make decisions?

NF: Yes.

RN: What do you find challenging about making these drawings?

NF: There’s really no room for error in my process, so a good drawing is rare. I have to try not to get discouraged, because so many of them don’t come out right. I just have to start over.

RN: It’s an apt metaphor for daily life.

NF: Yes, that’s true.

RN: Can you tell us about how you came up with the idea for Coriolis (2010; fig. 4)?

NF: Yes, I would love to tell you. Because there were so many woven patterns in the watercolors I was making around that time, I started thinking about textiles and decided to learn how to sew. One day I went to the fabric store with a tunic that I wanted to copy. The woman there gave me what she said was patternmaking material, and I spent that weekend on my hands and knees in the studio, trying to draw a pattern. The patternmaking material was covered in red dots—a dot matrix. I was surrounded by dots, and the material was semitransparent, so the dots were coming in and out and all around me…. I quickly lost interest in the idea of trying to make something to wear. I thought: “This is great material. I should do something with this.” I started to play with layering it. I thought: “This is preprinted material! It’ll save so much time.” Well, I quickly realized that it’s mass-produced, so the dots aren’t printed perfectly.

WHK: The register is bad.

NF: The register is bad, and in order to align them on top of each other…it just wasn’t going to work. I realized I would have to draw all my own dots. [Sigh.] Which is of course so much more true to my nature and way of doing things. I started searching for the right material to use, and as has happened countless times over the years, Ed Green arrived at my studio with a roll of Holotex, which is a polyester material. Ed also made me some wooden drawing tools, which I used to stamp the ink onto the Holotex. I would apply color to the tool and then stamp it down to make each dot.

I started to play with the arrangement of the Holotex sheets, and I kept thinking, “How am I going to hold these sheets together?” I wanted to stick them together, but I didn’t want the adhesive to show. I realized that I had only the space of the dots under which to hide adhesive, so I made a double-sided tape dot for every single drawn dot, using a Japanese screw punch.

Play to hear Nicole Phungrasamee Fein speaking about the discovery of her work Coriolis.

Figure 4. Nicole Phungrasamee Fein, Coriolis, 2010

Ink and tape on polyester, 18 3/4 x 18 3/4 inches (47.6 x 47.6 cm) © 2012 Nicole Phungrasamee Fein

The original idea for Coriolis was that the dots would rotate around the center. That was what I wanted to see happen. I had arrayed all of my sheets after months of preparation, with the dots and all the tape on them. One day, when I thought I was ready to remove the release paper from the double-stick tape and actually adhere all of it, I started to move the stack, and the sheets slipped from my fingers. They arrayed themselves into Coriolis by chance. I was stunned—in awe and just silent. I couldn’t move. I stood there looking at this pattern; I didn’t know what it was, and I didn’t understand it.

I quietly tiptoed upstairs and whispered to Mark and [my son,] Felix: “Something just happened in the studio. You have to come and see.” We looked at it together, and we didn’t understand what it was, but it was far more interesting than what I had been planning to do. For days, I stood and looked at it. I studied it and tried to figure it out, tried to understand it enough to intentionally do it. Yet I only had those sheets prepared to work with, so one by one, I started removing them to remake Coriolis.

WHK: That’s amazing, because you probably had a fairly square original pattern for it.

NF: Yes, my plan was perfectly symmetrical and very predictable. In Coriolis, there’s no center of gravity. There’s no single point around which the dots rotate. Some recede and some come forward.

RN: They array themselves within a very three-dimensional space.

NF: Yes.

RN: There’s a meditative and infinite feeling to looking down into Coriolis that references, in a lot of ways, your watercolors—but in a more dimensional way.

NF: Yes, within a deeper space…

RN: Is your work a sort of diaristic exercise?

NF: Yes, it is. The title of each work is the date of its completion—just a way of marking for myself at what point in my life I made each one.

While the test sheets are notations for formal drawings, all the works are notations for my life. The finished works show something about my state of being on a particular day; the individual lines record the moments.

RN: Do you find that there’s a correlation between the drawings that you consider failed and a certain way that you feel?

NF: Yes, I think so. It depends on why a drawing has failed, but oftentimes it’s because I wasn’t feeling steady or able to focus enough—or to slow down enough.

RN: Are you trying to slow your life down enough to make each drawing, or do you make each drawing because you want to slow down?

NF: I draw in order to slow myself down. The practice of drawing keeps me centered. We have gotten very busy, and I hope that I can bring a sense of slowing down to other areas of my life. I feel like the world we live in right now moves so quickly, and there are so many different directions to go in every day. I am truly blessed that my life is filled with a loving family, dear friends, and lots of fun, but I do treasure my studio time. My goal is to be present and attuned to whomever I am with and whatever I am doing.

RN: Is there something about drawing daily that helps you?

NF: Drawing is always better when it’s a daily practice. I take any window of time that I can. That time becomes sacred. The rituals of the practice help to quiet my mind.

I’ve found that when drawing is a daily practice I have a good rhythm that creates a momentum. The work develops and evolves much more readily than it does if I’ve taken a break. But when I do take time off, I return with a greater appreciation for the practice. I see the work with fresh eyes. This new perspective brings a welcome shift.

RN: Do you have a sense of how the patterns you make have evolved from earlier pieces to the present?

NF: The very first patterns were the simplest, the most basic: one line touched the next line, and a field was made out of these lines touching. One day, I turned the paper ninety degrees and crossed over those lines, and a grid appeared. Every drawing since then has been another iteration, a variation on that idea: changing the spacing of the overlapping, changing the width of the line…. Each one comes after the next. I’ll see something happen in one drawing, and it’ll spark something I use in the next.

RN: The patterns you develop are based on things you observe while making your drawings?

NF: Yes, and while working things out on the test sheets. One drawing leads to the next as a natural progression.

RN: Where do you see these patterns going, or do you feel that they have fully arrived?

NF: Every time I feel that I’ve arrived, they evolve. Something shifts that takes me in a new direction. But at the same time, I feel like I’m doing the exact same thing I’ve always done—and that is one line after another.

I do keep coming back to the simplest drawings, in which each line touches the edge of the previous line. Those drawings keep me grounded. They are the essence of my practice. So perhaps the very first one had fully arrived.

Play to hear Nicole Phungrasamee Fein speaking about the “slowness” of her process in conversation with Wynn Kramarsky.

Notes

Nicole Phungrasamee Fein

Wynn Kramarsky

Rachel Nackman

Janet Cohen in Conversation

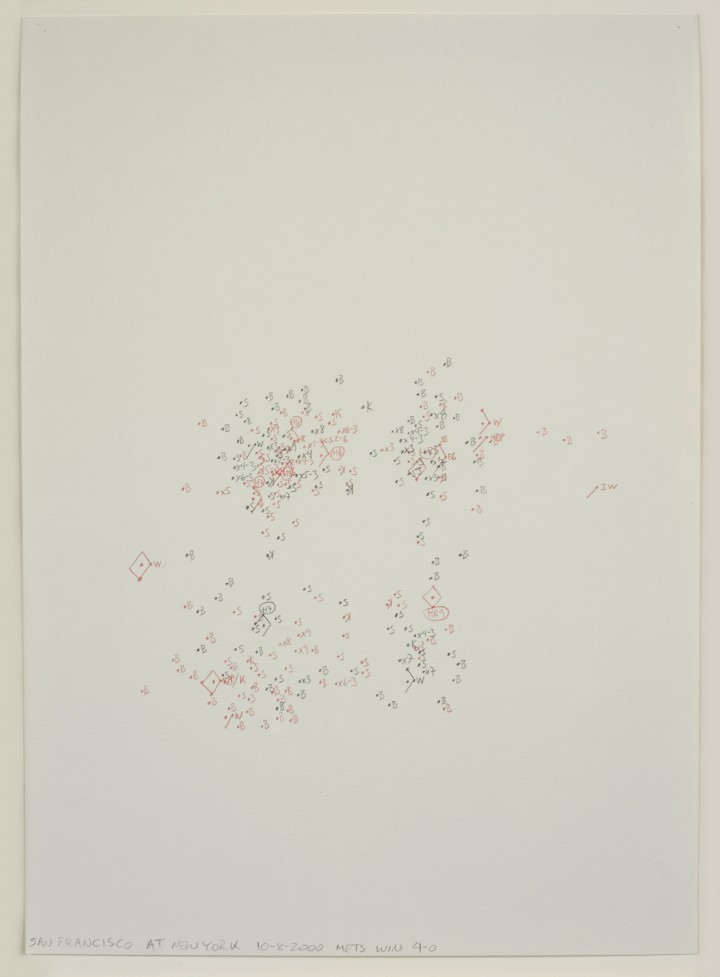

Figure 1. Janet Cohen, San Francisco at New York, 10-8-2000, Mets win 4-0, 2004

Graphite on paper, 9 1/4 x 13 inches (23.5 x 33 cm)

© 2004 Janet Cohen

Janet Cohen

In Conversation with Rachel Nackman & Michael Randazzo

April 2012, New York

Rachel Nackman: Can you tell us how you became acquainted with baseball and started making these drawings?

Janet Cohen: I grew up in Baltimore when the Baltimore Orioles were good. They went to the World Series in 1966, 1969, 1970, 1971, and 1979—five times by the time I was nineteen years old. But I wasn’t actually that into baseball as a kid. I had some baseball cards, in the typical way that most kids had baseball cards back then. I went to college in Philadelphia and was aware that the Phillies were really good at the time, but I had no great interest in watching the games. I was always a casual baseball fan.

I didn’t start making these drawings until after I graduated from Yale (the School of Art), where I studied painting and printmaking. One night I was doodling in front of the TV while watching a baseball game, just making marks on the page. I kept that drawing in my notebook for a year or so, and I realized, “I can probably do something with this.” And then, “What do I do with this?” That led to the past twenty-something years of work.

Initially I was trying to document the time of the game, although, as it happens, I ended up documenting the space where things happen. Over the years I’ve focused on both explicitly documenting the time of the game (marking off time in seconds) as well as working at making the drawings more self-contained, by which I mean that all the information you need to understand the drawing is within the drawing, not located elsewhere.

In more recent drawings, which have evolved significantly since 2000, I have been watching games and trying to find the pivot point, where the lead irrevocably went from one team to the other. That is the moment I’m trying to capture.

RN: A moment of high tension?

JC: Well, not high tension—just the moment when one team took the lead, and that was it for the rest of the game. The point at which, in an odd way, the rest of the game was sort of irrelevant. And Michael, I’m still trying to figure out how to draw game 6 from the 1986 Mets season . . .

Michael Randazzo: Right. That moment.

RN: What happened in game 6?

JC: The Mets were one strike away from losing the entire World Series to the Red Sox, and the Red Sox totally fell apart. It was a series of exceedingly fortunate events for the Mets.

The drawing included in this show is an old drawing. This is from when the Mets were good, during the last season they went to the World Series. It was in the playoffs against the San Francisco Giants, October 8, 2000. This was a great game for the Mets.

MR: This was a game that had minimal action; it was a one-hitter pitched by Bobby Jones.

JC: That’s probably why I chose to draw it. There had been no no-hitters thrown in the history of the Mets. It’s one of those statistical oddities, part of the curse of the Mets. A one-hitter is probably as close as the Mets will ever get to a no-hitter.1 This was a pretty good game.

MR: It was a good game from the action side, but what about from the drawing side?

JC: I would say that it’s not bad from the drawing side. I was surprised to see that in this drawing I was marking the pitches only as balls or strikes, adding no sequences or connections. Over time I’ve drifted toward trying to break things down into smaller periods of time, as a way to make things more legible.

RN: Can you tell us how you developed your system of notation?

JC: It started as a jumble of numbers, counting up from one until the final pitch of the game. I draw the home team’s pitches in black pencil and the away team’s pitches in red pencil. For the very first one, I was just watching a Sunday night game and drawing—this first pitch goes here; this second pitch goes there.

RN: Can you explain pitch location?

JC: Pitch location is pretty simple. It’s a matter of where the pitch crosses the plate in the plane of the strike zone. This is the conventional system that you’ve seen throughout the drawings.

RN: So the drawing documents you watching the game? Do you make these drawings while you’re at the game?

JC: It would be almost impossible to do these at the game. The drawing is premised on what used to be the conventional way of showing games on the TV: the camera is at about center field, and you almost see what the pitcher sees. (Since the TV camera can’t be directly behind the pitcher, it is slightly off from 180 degrees away from the pitcher.)

MR: Which, I’ll add, is 95 percent of what people see of a game on TV.

RN: Do these drawings take a bird’s-eye view of the strike zone?

JC: No, this is the straight-on elevation, as if seen from the center field camera. That is one thing that has stayed consistent throughout.

RN: When you’ve made adjustments to your system, what have your goals been in making those changes?

JC: Recently I’ve been concerned mostly with legibility. Over time my decision making has also become a matter of figuring out how much of the notation of the scoreboard I want to show. I see my current series of drawings as doing a pretty effective job of telling what happens in a game.

RN: When you’re thinking about telling that story, are you also thinking about the way the final result will look?

JC: Yes and no. I make plenty of decisions prior to starting a drawing (or a series of drawings) about paper size, drawing tools, and a marking system. However, once I begin the drawing, I don’t change the rules—I don’t make aesthetic decisions once the game starts. You should be able to look at the drawing without my being there, and say, “Okay, this is what’s going on.” I don’t know if there’s a polite way to put it, but I don’t think you should have to read something akin to a small novel to find out what’s there in front of you. The drawing that you have in front of you should be sufficient, combined with its title.

If you were Michael, who knows baseball, you could read the drawing and know what’s going on. But at least half the people who look at these drawings look at them in a more formalist way: “Well, why are those numbers and symbols arrayed in that setup?”

From what I’ve experienced, people who don’t know anything about baseball don’t really seem to have a problem with the drawings. It doesn’t seem to be an impossible bar to understanding.

MR: But effort on the part of the viewer will bring rewards?

JC: Sure. Effort will bring rewards, but you shouldn’t have to have a tour guide there to tell you what’s going on.

RN: Where do you work on these drawings?

JC: Normally I work on them either with a pad in my lap or at a small drafting table.

RN: Would that be in front of the TV, where you’re watching the game?

JC: It would be with the TV (or a computer monitor) not too far away, so that I rarely have to replay a pitch. I sort of consider it cheating to replay parts of the game.

MR: So you try to capture a pitch at the moment that you witness it. You’re in the zone of the game.

JC: Occasionally I get a bit of a brain freeze and have to replay pitches, but I try not to do that. It’s not a matter of trying to make the drawing perfectly, the way computer graphics can now capture a game.

MR: So the drawing is also about human perception?

JC: Yes. The same way a strike exists if the umpire says it’s a strike. It’s about the way one human perceives one issue and one event. Frankly, sometimes a good game produces a lousy drawing. Sometimes a lousy game produces a surprisingly good drawing. How good or fascinating the game is, to a baseball fan, has no relationship to whether it turns out a “good drawing.”

RN: Do you mean a good drawing visually?

JC: A good drawing in terms of visual pop or interest. I use a system that is generated by what the pitcher does, what the batter does, and what the runners do. It’s a bit like a Sol LeWitt system set loose.

There is really nothing intuitive about this process. It very roughly draws from LeWitt’s statement “The idea is the machine that makes the art.” His caveat, as I understand his writing, is that there are good ideas and bad ideas; all ideas aren’t equal.

In my catalogue of 162 drawings from one season, Estimating Pitch Location (1991–96), there were plenty of lousy games. The lousy games stay in with the good games. It’s not a matter of deciding that I’m going to show only the drawings I like. For example, if the plan ahead of time is to show a certain number of drawings of World Series games from a certain year, I show all the drawings, despite their greatness or their ugliness.

The drawings can be painful to complete, especially when a team that you don’t like is doing well. It’s annoying to deal with that. But you know, it’s work. The year that I documented Mets games—the season of 2007—it became really difficult at the end of the season to be drawing a Mets game.

MR: Did that influence the way that you reacted to the work?

JC: No, I just kept doing it, just plugged away. It kept getting worse and worse as September wore on, especially the last couple games. The Mets totally fell apart at the end.

MR: It was an epic collapse.

JC: An epic collapse, in epic proportions.

MR: Who taught you baseball scoring?

JC: I don’t know. I probably picked it up from a program at a game—nothing fancy, and there’s no real right or wrong to it.

MR: The idea of scoring the game is as old as the game itself. It’s a pretty well known system.

JC: Right. If the scorecard has been kept properly, somebody who’s reading the scorecard should be able to have good picture in his or her head of what happened during the game. I guess the point of keeping a scorecard is to have it for posterity.

MR: It’s a moment frozen in time.

JC: It’s a way of documenting events. Scorecards probably predate games being broadcast on the radio or television. (See Roger Angell’s short essay “Box Scores,” from his first collection of baseball writings, The Summer Game [1972], for a lyrical discussion of, among other things, box scores and balance sheets and the mathematics involved in baseball. For what it’s worth, any baseball fan should read everything Angell has written on baseball.)

RN: Do you want people to recognize the scorecard as a genesis for what you’re doing with the drawings?

JC: I never thought about it like that. I don’t necessarily want somebody to have a Proustian moment: “Oh yes, I remember that I kept score back when I was ten.” That’s not the goal of the drawing.

The goal is to try to document a mundane activity. These drawings really come from my need to do something other than random mark making generated by no system. It’s a nice coincidence that I get to watch something that I like to watch when doing my work. But in answer to Michael’s question, it’s not really about fandom. I’m constantly in search of other prosaic activities to document. I’ve been thinking about documenting the search for a parking spot; I’ve made some vague attempts at it, but I have yet to find a way to do that and do it safely . . .

Notes

1. On June 1, 2012, Johann Santana pitched a no-hitter for the Mets—the first and only no-hitter in the fifty-year history of the team.

Bios

Janet Cohen

Rachel Nackman

Michael Randazzo

In addition to his academic pursuits, Randazzo also helps organize conferences and special projects, including BLUR_O2, Power at Play in Digital Art and Culture with Creative Time, The Future of War with the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and The Brooklyn Cup for Kids with Young Rock Soccer Academy. A sometimes commentator on the New York sports scene for The Fort Greene/Clinton Hill Local, Randazzo resides in Brooklyn with his wife and two children.

Frank Badur in Conversation

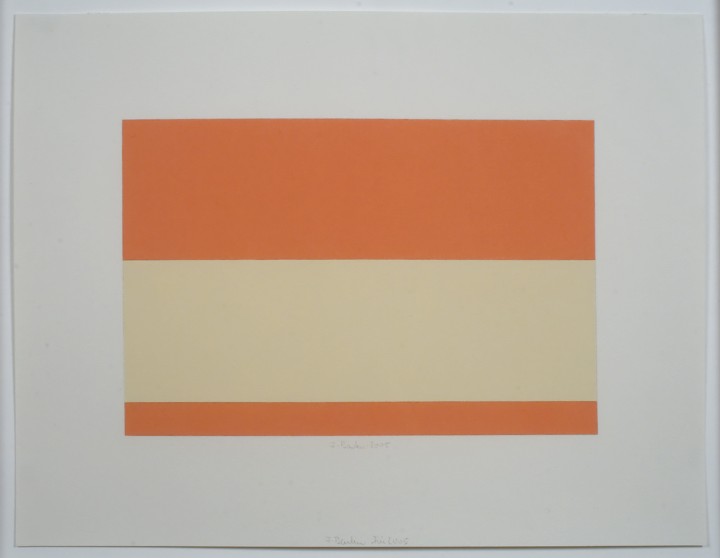

Figure 1. Frank Badur, Untitled (Fin), 2010

Gouache and graphite on paper, 14 1/4 x 18 inches (36.2 x 45.7 cm)

© 2012 Frank Badur

Frank Badur

In Conversation with Wynn Kramarsky & Rachel Nackman

August 2012

Frank Badur: The process of making a drawing begins with an impulse. Very often my drawings stem from my interest in architecture or in nature. I may also be thinking about music, Asian philosophy, or Asian poetry. But—and this is important—my work is never narrative; those sources provide only the impulse to start my drawings.

I don’t follow any system. The process of making a drawing, for me, is not systematic. If I’m in my studio and I’m absorbed in making a drawing, then the drawing tells me what my hand has to do next. The only things that are predetermined about each drawing are the measurements of the support and its orientation. Often the drawing starts with a very simple grid, and then I start to form my idea. The process develops more or less intuitively.

Like the Taoist yin and yang, my freehand irregular graphite grids provide a complementary contrast to the very precise work I do with gouache and a ruler. I like this contrast. I see the irregular grids as diagrams of my awareness as I go through the process of drawing. It’s very interesting for me to look at a drawing and to see how engaged I was, or how anxious, or how quiet my environment was.

Rachel Nackman: The freehand irregular grids can be read as a record of your mental state while making the drawing?

FB: Absolutely. Color is also an extremely emotional medium, and for me it too creates a very specific atmosphere. If you look at my drawings, I think you can observe all kinds of different color atmospheres. I have a huge color memory from my travels—you could call it a virtual color library. This is what I use in my studio.

For example, when I was in Kyoto, I was absolutely overwhelmed by the Katsura Imperial Village—by the balance of symmetry and asymmetry in the architecture, by the use of very pale colors. Years later I remembered what I had seen there, and it influenced a whole group of drawings. However, the reference is never direct; color is just something that comes back to me, and then I use it.

Wynn Kramarsky: You’re saying that your drawings are not reproductions of things you’ve seen in your travels, but they’re records of your emotional responses.

FB: Right. That’s also how I came to understand Agnes Martin’s paintings. I was in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and I thought: “Wow! These horizontal layers of light, of desert, of color—that’s what I see in the paintings of Agnes Martin.” Her work is not narrative or directly referential, but I think that she was attuned to color impulse.

RN: The impulse or the emotional response that you have to your environment then allows you to make color choices in your drawings, as well as choices about the type of line you’ll apply or about the type of grid you’ll apply?

FB: Yes. Each drawing starts out very simple, and then it becomes more and more complex. Very often I’m surprised when the drawing is finished. Sometimes I’m happy, and I can agree with my drawing. But sometimes I have to go back into it.

RN: When you have a final result that doesn’t please you or that doesn’t fit with what you were interested in achieving, you go back and rework things?

FB: Absolutely. Or I throw it into the garbage. [Laughter.] Sometimes when I make one drawing, I get the idea for the next drawing. If I’m very satisfied, then I may have the impulse to do another drawing—a third or a fourth drawing. The whole complex of my drawings grows when I’m working in my studio.

Figure 2. Frank Badur, Untitled (Fin), 2005

Gouache and graphite on paper, 13 3/8 x 17 3/16 inches (34 x 43.7 cm)

© 2012 Frank Badur

RN: Can you then look back at a body of work from a certain period and read a certain linear progression in the drawings that you made during that time?

FB: Yes. I can see my passing interests or my notions about other artists’ works. I can read all of this.

WHK: You first came to the United States in the early 1980s, and you’ve said that your exposure to contemporary American art at that time was eye-opening. Were you also exposed to Native American artwork while visiting the States?

FB: Yes. After my first trip to the United States in 1982, I returned many times to visit the Southwest. I went hiking with the Navajo Indians, and I learned about Navajo, Hopi, and Pueblo culture. Many of the Pueblo were potters, and I was utterly fascinated by the patterned drawings they made on their pottery. They are highly abstract, and they also have no system—it comes from the inside out. When I asked one of the oldest Pueblo potters how she made these drawings, she told me: “I don’t know. I think I get it from my ancestors, and I can do this only if I find a balance in my family and balance in nature. Only then am I able to do it.” I understood this so easily and so deeply.

RN: You found in studying Pueblo pottery that abstract pattern itself was evocative and that the artist was acting almost as a medium to deliver that pattern?

FB: Yes, absolutely. Each piece of pottery is almost like a piece of sculpture—the artist builds up the clay and smoothens the outside of the object by hand so that he or she can apply the drawing to its surface. They’re very involved with the pieces they create.

RN: What they do is develop a relationship with the support.

FB: Yes.

WHK: Occasionally you’ve used special handmade paper. Do you choose that support because you specifically want to make a drawing on handmade paper, or do you do so just because you have handmade paper available?

FB: I don’t just use the paper that’s available. I choose whatever is the right material for my technique.

RN: Can you tell us about the different mediums you use in your drawings?

FB: When I choose a medium, it’s also in order to engage with the specific characteristics of that medium. For example, if I make a woodblock print or an etching, I am working with those techniques in order to achieve a particular visual result, which I cannot find in another medium.

RN: Are your drawings then celebrations of these various mediums?

FB: Absolutely. I always have an idea of what I want to do, and to come close to the idea, maybe I need a brush and paint, or I need a pencil, or I need to make an etching or an aquatint. So the result is what leads me to the medium.

RN: The drawings on view here are made with gouache and graphite. Can you tell us what it is about gouache and graphite that attracts you?

FB: Yes, of course. Gouache is wet, and graphite is dry. To apply gouache, I use the brush; for graphite, I use my pencil. So the mediums and tools are soft and hard. These are opposite principles, like yin and yang. I like this—hard and soft, wet and dry. It’s a wonderful way to work.

RN: Can you tell us what it’s like to make these drawings?

FB: Making a drawing is usually a very slow process. Very often I work on four or five drawings simultaneously, so if one drawing needs time to dry, I focus on another drawing. It’s almost like a family—you have to figure out which child needs a little bit more attention than the others.

I think the aura of a work on paper is different from a painting on canvas. For me, drawing is very intimate, and painting is something you can feel or measure with your body. A work on paper is really in your hand: you measure it with your hand, and you hold your tool in your hand. Painting is very physical and requires a lot of distance from the canvas. With a drawing, I have a piece of paper in front of me, and I’m completely by myself and absorbed by the work. I’m in a contemplative state for hours.

Sometimes when I finish something, I realize I’m hungry and look at my watch—only to see that four or five hours are completely gone. Sometimes I have to ask myself: “How did this happen? And who made this drawing?”

RN: As you’ve said, you sometimes feel surprised by what you see.

FB: Yes. It’s almost like an adventure tour. I have an idea, and I try to come close to it. But sometimes I open a new door, a new space, and I have the freedom to make something else instead.

Bios

Frank Badur

Wynn Kramarsky

Rachel Nackman

William Anastasi in Conversation

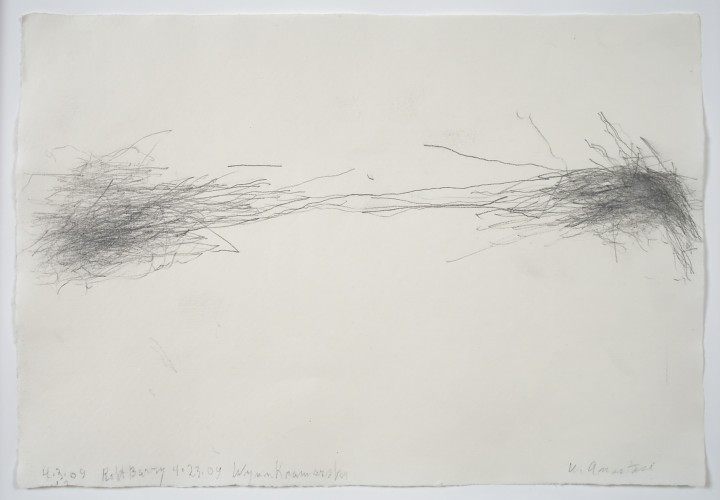

William Anastasi, Untitled (Subway Drawing), 2009

Graphite on paper, 8 x 11 1/2 inches (20.3 x 29.2 cm)

© 2012 William Anastasi

William Anastasi

In Conversation with Rachel Nackman

March 2012, New York

Rachel Nackman: When did you begin making subway drawings? What was the genesis of that activity?

William Anastasi: The genesis of the subway drawing was the walking drawing. These were done holding a pad and walking, watching where I was going rather than watching the pad. I started doing this in Philadelphia in the early 1960s. To my memory, the pocket drawings weren’t started until I was going to films at MoMA, so I was here in New York by then. And the pocket drawings at films led to pocket drawings in the subway. Those reminded me of some different subway drawings I had done before coming here.

RN: You also made subway drawings in Philadelphia?

WA: I made subway drawings in Philadelphia, and I made walking drawings in Philadelphia. The only one of the three types of drawing that wasn’t started there was the pocket drawing.

RN: How did you decide to make the subway drawings and walking drawings in Philadelphia?

WA: I love walking. I find that walking does something to my thinking, to my mental process, that is different from sitting or lying down. I learned that about myself very early. I was already a runner, but walking is extremely different from running, and I think that’s one of the important things about it. I’ve tried running drawings and I don’t like it so far.

RN: It sounds difficult.

WA: Yes. Maybe I’m afraid I’ll fall on my face; I don’t know. But the walking drawings gave me an idea. When there’s motion, let that motion, rather than predetermination, be the energy for the drawing—rather than consulting the aesthetic prejudice of the moment, which we usually do when we draw if our eyes are open. With the subway drawings, my eyes are closed, for the most part, or looking at the floor or the feet of the people across from me.

Right from the beginning of the process, I wasn’t interested in looking. I think that was part of my original idea, because with the walking drawings you have to watch where you’re going, so you’re automatically not looking. I think that’s why the walking drawings had something to do with the subway drawings—it makes a lot of sense.

William Anastasi, Untitled (Subway Drawing), 1973

Graphite on paper, 7 5/8 x 11 1/8 inches (19.4 x 28.3 cm)

Collection of the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

© 2012 William Anastasi

RN: When you started making your first walking drawings in Philadelphia, were you walking with a destination?

WA: For the most part, I was walking in the big apartment I had. I think I was embarrassed to do it outside in my neighborhood. I’m not embarrassed to do it in New York, though, walking to the Hudson River, although sometimes people comment. One time, a fellow came up next to me as I was walking because he was very interested in what I was doing and had questions about it.

RN: Did you stop and talk to him?

WA: I didn’t stop; I kept walking. But we talked while I kept walking and drawing.

RN: You can do a lot of things at once.

WA: I’ve done numerous subway drawings, as you know. I don’t get on the subway without doing it, because I find it’s another form of meditation–a kind of meditation I learned before I actually learned to meditate.

RN: When you make a subway drawing, generally there’s a destination that you write along the bottom.

WA: I usually put where I’m going, or whom I’m meeting, along the bottom. I have one here today that has Wynn Kramarsky’s name on the bottom.

Someday, I would like to do a show titled The Idiots, They Were Making Fun of You. The reason for that is that I used to play chess with John Cage every day. He knew my subway drawings, and it was a great honor that the first things you saw when you walked into his home was a group of three subway drawings. He liked the idea very much.

In my memoir The Cage Dialogues, from 2011, I talk about the time that John asked, one day, “Are you going home by subway?” I said yes. He asked, “Are you going to do a subway drawing?” I said yes. He said, “Could I come?”—it was amazing that he wanted to—and I said yes, of course. My eyes were closed during the whole drawing, and when we got off the train, John said, “The idiots, they were making fun of you.” It was extremely uncharacteristic of him—extremely—to ever talk that way about someone. It would be an interesting thing, for this centennial year of Cage’s birth, to do a show somewhere with that title.

RN: What would be in that show?

WA: Well, I guess my work that people make fun of. For example, I’m sure that would include the walking drawings. I’m sure some people think I’m quite crazy. Or the subway drawings—when my eyes open as the train stops, it does look as though some people think I’m loony.

RN: You are very conscious of the fact that people are watching you when you make the subway drawings.

WA: There’s no question. Thousands and thousands of people. I’m sure it’s true every time I’m on a crowded subway. Some people obviously like it and don’t just think I’m nuts. But some think it’s strange—“What’s wrong with that guy?” And maybe, if they’ve ever done a drawing themselves, some think, “Oh, that’s a nice idea.”

RN: You’ve said that your day tends to be better when you make a subway drawing.

WA: Usually it is. It is so true that, at a stressful time, I’ll find myself searching for an excuse to take the subway down to New York Central Art Supply, or somewhere else.

RN: Can you tell us what it is about the daily process of making the subway drawing that appeals to you?

WA: I think I do know, in my case, what appeals to me. It was many years after I began the subway drawings that I learned a meditation practice. And a meditation practice is very valuable if you do it every day, so much so that the person who taught me advised, “If you don’t have half an hour, do five minutes, no matter what. If the house is burning down, do five minutes.” That’s the way it was put. And it’s true. There’s something about the quotidian that is valuable. And I draw every day.

I’ve been drawing every day, probably since grade school, so it’s kind of part of me. As a child, I’d even put the date and my name on my drawings, whereas when I thought of becoming an artist as an adult, at first I wouldn’t put my name on them because I dared not think I was really an artist. I was afraid to call myself an artist until August 15, 1960. That’s when, as an adult, I first put the date and my name on a drawing. It was like jumping off a building.

RN: Do you remember what drawing that was?

WA: It was an abstract drawing. That’s all I remember. I still have it somewhere. It was certainly made before I was making walking drawings. Before the walking drawings, my drawings, when they were abstract, were from my mind, or from something if something was there to draw. I would do drawings of my wife at the time and of my kids.

RN: And then the walking drawings happened in the early 1960s, after you put that first date on a drawing.

WA: Oh, yes. My mother had a mantra—she’d say, “Of course, the best thing you can be in this life is an artist.” That is literally one of my earliest memories. I don’t know where she got that idea, but it’s one of the things that made me afraid to sign something as an adult.

When I learned meditation, it was then that I thought I’ve been, in a way, meditating already, by drawing virtually every day.

RN: When did you learn meditation?

WA: Dove Bradshaw and I have been together for something like thirty-seven years. It was right after I met Dove that I learned to meditate. She had studied meditation—Transcendental Meditation—and she had been practicing for a couple of years before we met. In the next ten years, she fell away from it. But in 1984 we read a New York Times article that said that even if you didn’t think it was working for you it actually was, that it was very healthy. It was then that I took the teaching more seriously, and that got us both starting again. Dove had a mantra. Since that was her practice attitude, I made up my own mantra, which happened to be row-dee. At the recommendation of my son Lawrence, I went to the Shambhala Center, which involves meditation with your eyes open, different from the kind of method I learned from Dove.

The Shambhala method is very simple: sit eleven or twelve inches off the ground with your legs crossed. You look at a clock or watch, and you say to yourself that you’re going to do this for a half hour. Then you settle your view on an area or a spot on the floor—so your eyes are not closed. You keep your eyes, as much as you can, on that area or spot. You settle your view there and pay attention to your outbreath, and that’s all you have to remember. Is your breath smooth? Is it rough? Is it fast? Is it slow? Is it the same as always? You simply pay attention. As soon as your mind is wandering about some unpaid bill or some difficult romance, you calmly go back to your outbreath. When you think it’s roughly half an hour, you shift your glance to the watch. When you first begin, you’re going to look up after fifteen minutes, and you’re going to realize it’s only been fifteen minutes, but eventually you get very good at it. I’m much better at it after these years. I can usually nail it within a minute or two.

I was already doing the subway drawings when I learned meditation, but the connection between them had never occurred to me. I knew I liked making the drawings. I knew it was valuable for me. I never would have used the word meditation, but after a while, I realized, “You’ve been doing your own form of meditation.” Blaise Pascal said, “All the troubles in the world can be traced to man’s inability to sit alone quietly in a room.” If you think about it, if enough men meditated, you wouldn’t have war, you wouldn’t have murder, you wouldn’t have all the troubles in the world. It can all be traced to man’s inability to sit quietly in a room. We’re busy beavers.

William Anastasi, Untitled (Pocket Drawing), 2008

Graphite on paper towel from The Modern restaurant, 16 7/8 x 16 7/8 inches (42.9 x 42.9 cm)

© 2012 William Anastasi

RN: Can you walk us through the process of making a pocket drawing?

WA: You fold a piece of paper until it can fit in your pocket, and then you put it in your pocket, and you use, usually, a 6B or 8B pencil. Soft. I just put my hand in my pocket, feel the paper, and draw. If it’s a pocket drawing, I’m usually also walking.

RN: When you’re making the walking pocket drawings, do you move the pencil yourself or do you just let the movement of your walking move the paper?

WA: To some extent both the pencil point and the folded paper are affected.

RN: When do you decide that you will pull out the paper, unfold and refold it?

WA: That’s hard to answer, because it’s not as though I decide. In other words, I’m not consulting the drawing and saying, “Is that enough?” The process is—what would you call it—phenomenological?

This particular drawing was inspired by the fact that it says “The Modern” on this napkin. I thought it was very funny that this was printed on that kind of paper. I still think it’s funny. I thought, “If it’s something funny, it’s a good thing to do a pocket drawing on.” There is also the thickness of the napkin to consider, which I found charming. If I make a pocket drawing with a different kind of paper, the wrinkles from folding it are more lasting. With this kind of napkin paper, the wrinkles for the most part disappear, so you see the drawing in a different way.

RN: This paper is almost like a textile.

WA: Yes, it behaves more like half fabric, half paper. In the pocket it works fine, because it conforms to your thigh and your hand. And then when you take it out, it doesn’t look like it was in your pocket because of the kind of paper it is. So I thought that was kind of interesting—that afterward it is going to look different from the normal paper I use.

RN: It’s the ideal support for your process.

WA: Yes. Except I like the wrinkles just as much as the no wrinkles. I just liked the idea that it was different. Some have wrinkles and this doesn’t: I thought that was something important.

RN: Have you found that your process of making a subway drawing has changed over time?

WA: The fact is, I thought of the subway drawings as some kind of therapy when I first started making them. I didn’t take them as seriously as I did my other drawings. I really thought drawing was drawing, and subway drawing was something else.

RN: Do you still feel that way?

WA: No. I now think it is part of what I do. In my other work I try to have the same kind of spontaneity that I see on the page when I do a subway drawing. It very often surprises me, even after all this time. I’m trying to get that spontaneity into the other work, which I make when I’m looking. But I’m never looking at the subway drawings while I’m doing them, whether my eyes are open or shut.

RN: So when you’re completely done with a subway drawing, then it’s revealed to you; at that point you see.

WA: I’m never finished with them. I can always see one and say, “I’ll do another trip downtown on this.”

RN: Do you see your subway drawing practice as in some way documenting a part of your life?

WA: No. Not consciously. I guess I don’t think that about any of the work. That’s for after I’m gone. People will probably do that later—but no, I don’t. That thought has not occurred to me.

RN: You just think about what you’re doing when you’re doing it, on a daily basis?

WA: I think artists usually do. I think artists are the opposite of curators. Good artists live in the present. We’re always changing; our taste is changing, our method and our madness are changing. Artists are the opposite of curators, probably, because curators are frozen. They specialize in a certain area. I’m not that way.

I still wonder whether I am an artist. And I think it’s the healthiest thing in the world, no matter what has happened to me. I think it’s because of my mother saying that the best thing anyone can be in this life is an artist. It’s as though a part of me, almost eighty years old, is saying, “Well, Mom, I wish I was one.” It almost brings tears to my eyes, but it’s true. I think I’m still trying to prove to her that I’m an artist, because I haven’t proven it to myself.

Bios

William Anastasi

Rachel Nackman