Meredith Malone on Robert Morris

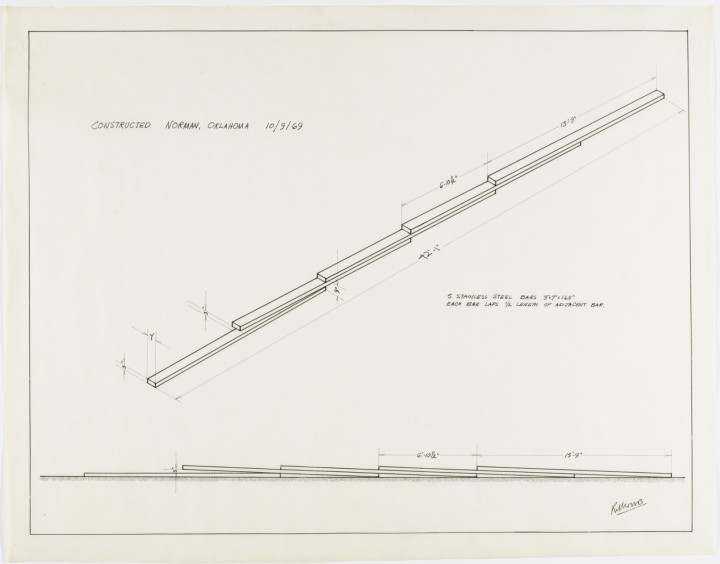

Figure 1. Robert Morris, Untitled, 1969

Felt-tip pen on transparentized paper, 20 x 25 1/2 inches (50.8 x 64.8 cm)

Gift of Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2012 Robert Morris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Robert Morris

by Meredith Malone

Robert Morris’s untitled ink drawing of 1969 (fig. 1) depicts a large temporary sculpture, comprising a progression of industrial steel bars, along with the words “constructed Norman, Oklahoma 10/3/69.” The drawing exists both as a descriptive diagram for a sculpture—providing elevation and aerial views, as well as measurements and notations concerning materials and construction details—and as a lasting record of the impermanent installation in Norman. The combination of multiple points of view and prescriptive text makes it possible for the viewer to understand and envision not only the final structure itself, but also Morris’s process of making it.

Rendered in a mechanically precise manner that reveals little of the artist’s hand, the drawing reads as impersonal and reductive. Morris spells out in block letters the simple system he employed to produce this temporary sculpture: “5 stainless steel bars 3” x 7” x 165” / each bar laps ½ length of adjacent bar.” The accumulated weight of the identical fifteen-foot bars was intended to keep the entire structure in place, without armature, as the units were successively stacked one on top of the other. The aerial view shows the sculpture extending lengthwise from left to right, and the hatch marks placed directly under the elevation view stress the work’s relationship to the ground. A significant disjunction exists, however, between the objective appearance of the drawing and the contingent character of the realized structure as experienced in real space and time. By positioning his long horizontal structure on the ground, the artist established a direct relationship with its setting, significantly realigning the viewer’s experience of modernist sculpture. Instead of approaching a discrete form on a pedestal—defined by fixed proportions and a specific, predetermined relationship to the spectator—the viewer could walk around, along, or even over Morris’s sculpture, a situation that called attention to the passage of time, shifting environmental conditions, and perception.1

In both the sculpture and the drawing, Morris maintained the simplified industrial aesthetic characteristic of Minimalism, of which he was one of the primary practitioners and theorists. He also emphasized the process of construction as much as, if not more than, the final product, a choice that reflects a shift in his practice in the late 1960s toward the exploration of increasingly indeterminate forms and activities. The present drawing shows just one variation of a provisional and permutable structure; the serial system of stacking he employed could be readily redeployed to create comparable configurations of varying lengths using different materials. Not long after the Norman installation, Morris constructed a similar work using five pieces of timber (12 x 12 x 144 inches) at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC, and another using twelve pieces of steel (6 x 18 x 24 inches) at the Pasadena Art Museum in California.2 As was the case with the initial installation, no physical changes were made to the materials used to construct either of these pieces; they were treated as readymades to be assembled and arranged rather than transformed.3 The lumber and steel were purchased by the respective hosting institutions, and it was the artist’s expressed intention for these materials to be bought back at the end of the exhibitions by the lumberyard and the manufacturer, in order to cycle them back into the economy. Speaking of his Corcoran Gallery installation while also making reference to his project in Norman, Morris stated: “The museum rented this piece really—the material can go back into circulation just as the steel can, and I like that idea—that I’m not doing anything to the material. I’m just using it in my way and it can go back.”4

In depersonalizing the fabrication of the work in this manner, and in using standardized materials that undergo no physical transformation and have no definite final configuration, Morris overtly denied accepted notions of specialized artistic skill or manual virtuosity. His untitled drawing remains an important document of the use of non-art materials, basic geometric forms, serial systems, and gravity as elements of an artistic process meant to exhort viewers to see beyond the prevailing conventions of sculptural practice.

Notes

1. Maurice Berger, Labyrinths: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s (New York: Harper & Row, 1989), 52.

2. For illustrations of these installations, see Michael Compton and David Sylvester, eds., Robert Morris (London: The Tate Gallery, 1971), 98, 100.

3. Michael Compton “Section IV: Various Metals and Resins,” Robert Morris, ibid., 85.

4. E.C. Goossen, “The Artist Speaks: Robert Morris,” Art in America 58 (May-June 1970): 111.

Bios

Meredith Malone

Robert Morris