Matthew Bailey on Agnes Martin

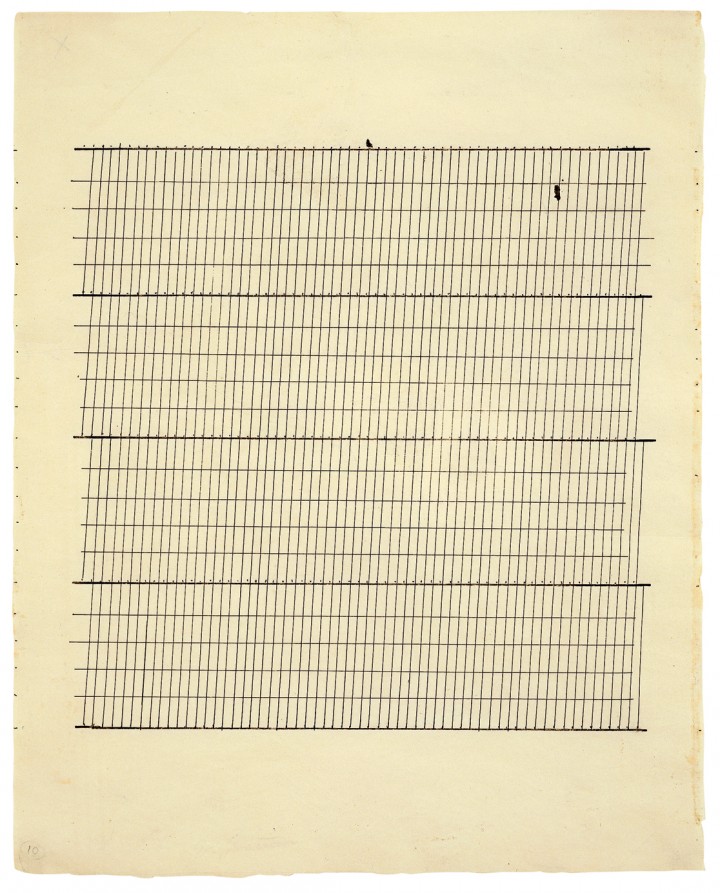

Figure 1. Agnes Martin, Aspiration, 1960

Ink on paper, 11 3/4 x 9 3/8 inches (29.8 x 23.8 cm)

© 2012 Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

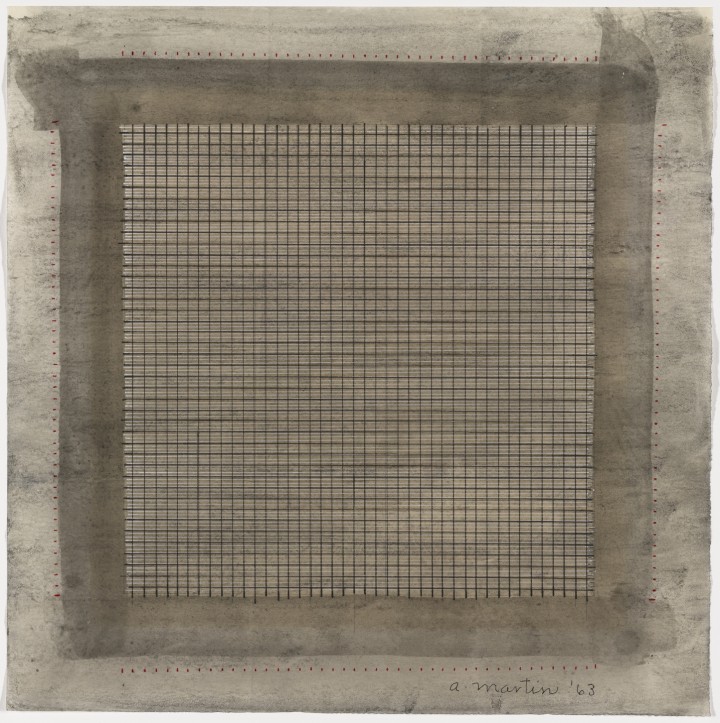

Figure 2. Agnes Martin, Wood I, 1963

Watercolor and graphite on paper, 15 x 15 1/2 inches (38.1 x 39.4 cm)

Gift of Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2012 Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Agnes Martin

by Matthew Bailey

Agnes Martin was one of a number of artists whose unique brand of geometric abstraction was positioned apart from the heroic, fluid gestures of canonical Abstract Expressionism, which were thought to symbolize the inimitable psychic and somatic expressions of the individual artist. While maintaining a belief in art as a specialized sphere of aesthetic experience, Martin looked to more impersonal compositional strategies to suppress artistic subjectivity, instead privileging the relationship between the viewer and the work of art. To this end, in the early 1960s she began systematically using the compositional logic of the grid as a template for her aesthetic investigations. The three drawings on view in this exhibition exemplify her serialized exploration of formal variation, guided and limited by the geometric configuration of the grid. The monochromatic Aspiration (1960; fig. 1) is anchored by five horizontal lines drawn with pen and ink in the center of the sheet. Within each of these bands, Martin drew a series of more delicate lines: four evenly spaced horizontals of slightly differing lengths are contained within or protrude from the dense pattern of slanting vertical lines that they bisect. Although at first glance these patterns of lines appear perfectly parallel and congruent, a closer look reveals slight inconsistencies in angle, spacing, and length, as well as in thickness and weight. Portions of the lines are broken or faded due to alterations in the pressure of the artist’s hand.

The tension between the rigid system of the grid and the graphic variations permitted by Martin’s subjective choices and treatment of line becomes more complex in Wood I (1963; fig. 2). Here she overlaid in pencil a square grid on top of a thin black wash with subtle irregularities in tone and texture. Behind the graphite grid and over the wash, she also drew a patterned series of faint white horizontal lines. These lines generate an optical vibration in the graph, which is bound by dark, casually applied bands of wash extending beyond the parameters of the square.1

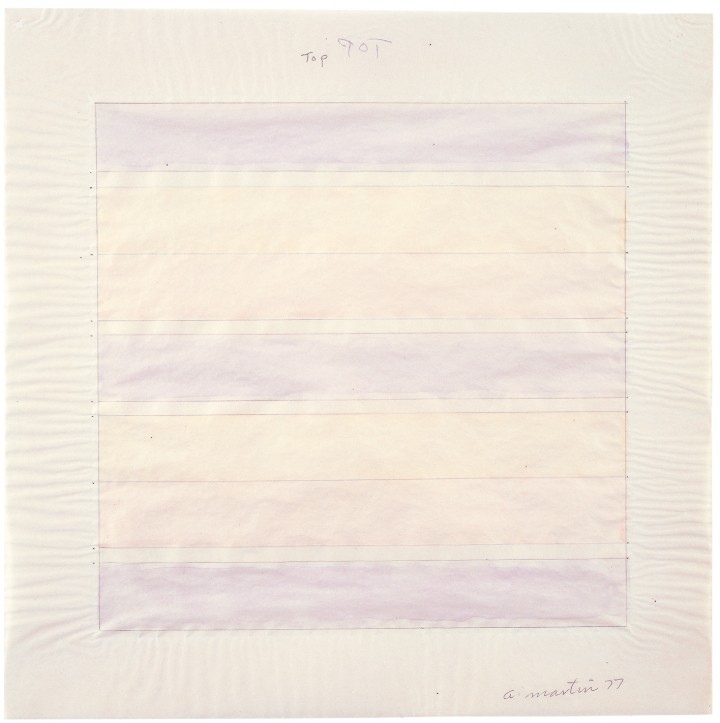

Figure 3. Agnes Martin, Untitled, 1977

Watercolor and graphite on paper, 15 x 15 1/2 inches (22.9 x 22.9 cm)

© 2012 Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Martin’s untitled drawing of 1977 (fig. 3) is distinct from these two earlier works in its exploration of the effects of watercolor. It is also representative of her later departure from the strict parameters of the grid and her experimentation with using squares and rectangles to create geometric configurations. The work presents bands of thinned pink, blue, and red wash framed within a lightly drawn square and overlaid by a rhythmic pattern of horizontal lines. Bleeding into the paper, with faint variations in saturation and tint, the luminous colored bands give the work a mystical, atmospheric quality that seems at odds with the rational, geometric contours structuring the composition.

Martin’s intimate and infinitely subtle works on paper beg close examination of their nuanced perceptual effects. Her fixation on the grid and geometric forms was driven by an interest in creating an elevated aesthetic experience with limited, systematic means. Despite the seemingly rational nature of her system, Martin believed in art as a realm of transcendent experience, much like nature itself. Titles such as Aspiration or Wood I allude to these sources of inspiration, her work reaching for the exalted just as it reflects the conflict between order and the arbitrary in nature. “All great artwork attempts to represent our joy in moments of clarity and vision,” she wrote in a letter to Barbara England attached to the back of Wood I. “Please study your response to art very carefully (and to everything else) as it is the road to self knowledge and truth about life.”2 For Martin, art was a spiritual endeavor, and she was devoted to making viewers conscious of “a wide range of emotional responses that we make that cannot be put into words.”3 Her concern with eliciting experiences of exultation and self-revelation, however—pointing to that “something which isn’t possible in the world / More perfection than is possible in the world”—hinged on the suppression of her subjective self, and the grid exemplified this “egolessness.”4 This logical system—together with sensuous variations in quality of line, sensitive shifts in tone or texture, and nuanced relationships between materials—pushed art beyond the trace of self-expression and toward the embodiment of universal experiences of truth, beauty, and perfection.

Notes

1. The red plotting marks along the outside edges of the image were likely used as a guide for the mechanical application of lines with a ruler.

2. Agnes Martin, quoted in Eun Young Jung, “Agnes Martin,” in Drawings of Choice from a New York Collection, ed. Josef Helfenstein and Jonathan Fineberg (Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2002), 106.

3. Agnes Martin, “Beauty Is the Mystery of Life,” in Agnes Martin, by Barbara Haskell et al. (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1992), 10–11.

4. Agnes Martin, quoted in Aline Brandauer, “Bearing Witness,” in Agnes Martin: Works on Paper, by Aline Brandauer, Harmony Hammond, and Ann Wilson (Santa Fe: Museum of Fine Arts, Museum of New Mexico, 1998), 13.

Bios

Matthew Bailey

Agnes Martin

Matthew Bailey on Ellsworth Kelly

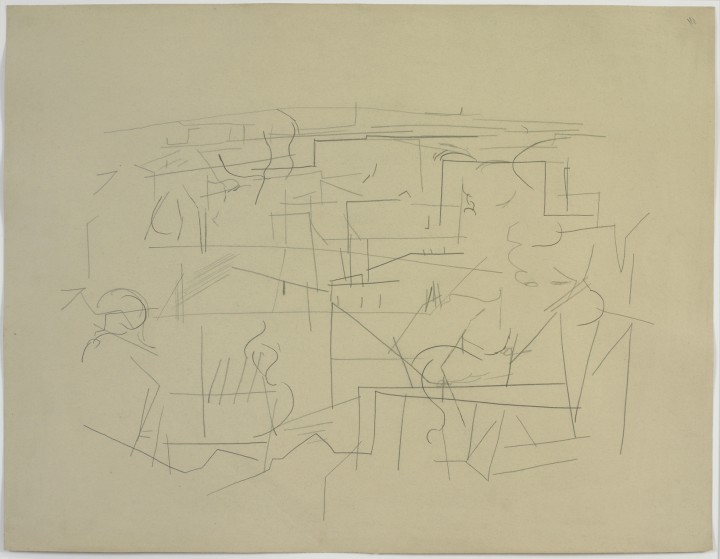

Figure 1. Ellsworth Kelly, Smoke from Chimneys, Automatic Drawing from Rue de Blainville, 1950

Graphite on paper, 19 3/4 x 25 5/8 inches (50.2 x 65.1 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, 2012

© Ellsworth Kelly

Ellsworth Kelly

by Matthew Bailey

In this loose, organic drawing of an abstracted scene of Paris, Ellsworth Kelly used the sparest of freehand notations to register the side or corner of a building, the slant and texture of a roof, and a curling wisp of smoke. Smoke from Chimneys, Automatic Drawing from Rue de Blainville (1950; fig. 1) is one of a series of drawings that Kelly executed while living in France from 1948 to 1954, in which the young artist experimented broadly with ways to “get the personality out of painting . . . to do paintings that were anonymous.”1 Employing a variety of chance procedures at this early stage in his career, Kelly embraced what the art historian Yve-Alain Bois has called a strategy of the “non-compositional.”2 Kelly’s turn toward the non-compositional was aimed at circumventing subjective expression and approaches to compositional organization that reflected the controlling will of the artist.

To create Smoke from Chimneys, Kelly enacted his own twist on the methods of Surrealist automatism, to which he had been exposed in 1949. In lieu of the Surrealist practice of relinquishing rational control in favor of unconscious processes, he instead drew scenes or objects from memory or worked “blind”—by drawing without looking at his support, with his eyes closed, or even while blindfolded.3 In this work it is likely that the artist transcribed an observed scene without looking at the paper and without monitoring his progress. This mode of working was a direct attack on conscious “motor control,” as Bois notes.4 Kelly’s method is revealed here in the way lines and forms haphazardly overlap and intersect, presenting a jumbled mass of curvilinear scribbles and irregular rectilinear contours that lose their representational function. At the same time, the drawing inevitably retains a sense of the impulse toward rational composition that the artist wished to purge from his work, a problem of which he was aware.

The composition is symmetrically centered on the paper, exhibiting overall a balanced organization of line and form. Moreover, the illusionistic nature of the imagery and the hint of spatial recession—suggested by the perspectival lines and overlapping shapes that recede into the background—also reveal a certain retention of control. As Bois has said of Kelly’s work in this series, “with this move a point of view is implied, and thus a subjective agency.”5 Plagued by the resurgence of rational control and subjective choice in automatic drawings such as this one, Kelly thereafter turned to more systematic strategies of chance, reduction, and serialization—including the creation of collages through random numerical drawings, the execution of monochromatic paintings, the use of grids, and the repetition of form—in an attempt to repress his own artistic agency.

Notes

1. Ellsworth Kelly, “Interview: Ellsworth Kelly Talks with Paul Cummings,” Drawing 8 (September–October 1991), quoted in Pamela Lee and Christine Mehring, Drawing Is Another Kind of Language: Recent American Drawings from a New York Private Collection (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 1997), 98.

2. Yve-Alain Bois, “Ellsworth Kelly in France: Anti-Composition in Its Many Guises,” in Ellsworth Kelly: The Years in France, 1948–1954, ed. Yve-Alain Bois, Jack Cowart, and Alfred Pacquement (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1992), 9–36.

3. Bois, “Ellsworth Kelly in France,” 24–25; Bois, “Kelly’s Trouvailles: Findings in France,” in Ellsworth Kelly: The Early Drawings, 1948–1955 (Cambridge: Harvard University Art Museums; Winterthur, Switzerland: Kunstmuseum Winterthur, 1999), 23.

4. Bois, “Kelly’s Trouvailles,” 23.

5. Ibid., 19.

Bios

Matthew Bailey

Ellsworth Kelly

Matthew Bailey on Donald Judd

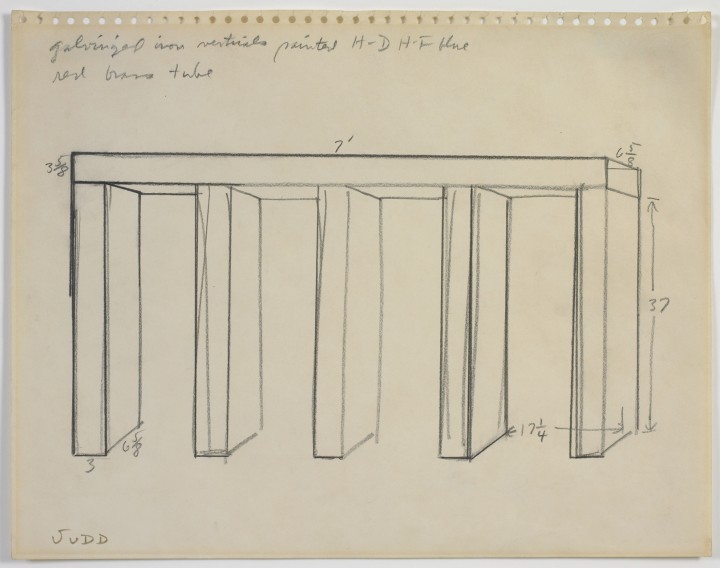

Figure 1. Donald Judd, Untitled, 1967

Graphite on paper, 10 3/4 x 13 1/4 (27.3 x 33.7 cm)

Art © Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Donald Judd

by Matthew Bailey

Donald Judd was one of the leaders of Minimal art, both as an artist and as a critic. His sculptural works, which he labeled “specific objects” in a seminal essay published in 1967, were characterized by streamlined large-scale geometric forms produced using industrial materials and processes of fabrication. Judd’s untitled sketch, also from 1967 (fig. 1), is a working drawing for one of a series of sculptures that he began producing in 1965. Each nearly identical object in the series consisted of a horizontal bar with five verticals, yet each displayed slight variations in materials and colors. The schematic work on paper includes handwritten notations for color and material, along with precise measurements for each plane of what Judd called “the brass with five verticals.” The drawing demonstrates the artist’s graphic distillation of “above all that shape.”1

By using aesthetic strategies such as symmetry and repetition, Judd strove to create an indivisible, unified three-dimensional form in which no particular element assumes visual or compositional focus. This was his way of avoiding what he called “the problem of illusionism” in traditional painting and sculpture: the use of compositional hierarchy emphasizing parts over the whole and the consequent allusion to some other symbolic world beyond the work of art itself. Instead, his literal objects were meant to assert their own holistic presence in “real space,” something “intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface,” as he wrote.2 Judd also deflected the associations carried by traditional art materials and circumvented the intrusions of subjective expression by having his objects manufactured by skilled laborers using industrial materials, thus distancing the artist’s hand from the act of making.

Judd’s Minimal forms were aimed at generating perceptual and phenomenological responses in viewers, enhancing their sensory awareness of physical space.3 Pictorial by nature and executed by the artist’s hand, this preparatory drawing seems antithetical to the cold, impersonal nature of his substantial objects. It also demonstrates the kind of perspectival illusionism that Judd wished to evade in his “specific objects.” It is no wonder that he diminished the importance of his graphic studies, claiming that they were “simple mechanical instructions for the production of standardized forms with industrial materials.”4 That he did not think of these as polished works for exhibition or presentation is demonstrated by the casual, schematic use of contour lines with no concern for shading, detail, or color.

Nonetheless, these diagrammatic sketches were a crucial component of Judd’s practice. As he once mentioned, they were a means of recording ideas for both past and future works.5 As such, these kinds of drawings served as an arena in which he experimented with and worked through abstract conceptions, demonstrating an incipient stage of his creative process in which he utilized the flexibility of the medium to sketch, notate, and diagram shapes, dimensions, colors, and materials. The cognitive immediacy reflected in his drawings is made tangible in the lightly drawn, cursory lines that he used to define the essential structure of the horizontal and vertical bars, over which he marked heavier and more decisive contours with the aid of a ruler to give his study a more detached, mechanical quality. For all Judd’s emphasis on the phenomenal experience of the three-dimensional objects themselves, without allusions to the artist’s hand or creative praxis, studies such as this reveal the degree to which he relied on drawing as a means of reconciling formal and theoretical abstractions—a practice he shared with many artists associated with Minimal, Conceptual, and Process art in the 1960s and 1970s.

Notes

1. Bruce Glaser, “Questions to Stella and Judd,” Art News 65 (September 1966): 58.

2. Donald Judd, “Specific Objects” (1965), in Complete Writings, 1959–1975 (New York: New York University Press, 1975), 184.

3. David Joselit, American Art since 1945 (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2003), 113.

4. Josef Helfenstein, “Concept, Process, Dematerialization: Reflections on the Role of Drawings in Recent Art,” in Drawings of Choice from a New York Collection, ed. Josef Helfenstein and Jonathan Fineberg (Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2002), 15.

5. Dieter Koepplin, introduction to Donald Judd: Zeichnungen / Drawings, 1956–1976 (Basel: Kunstmuseum; New York: New York University Press, 1976), 8.

Bios

Matthew Bailey

Donald Judd

Matthew Bailey on John Cage

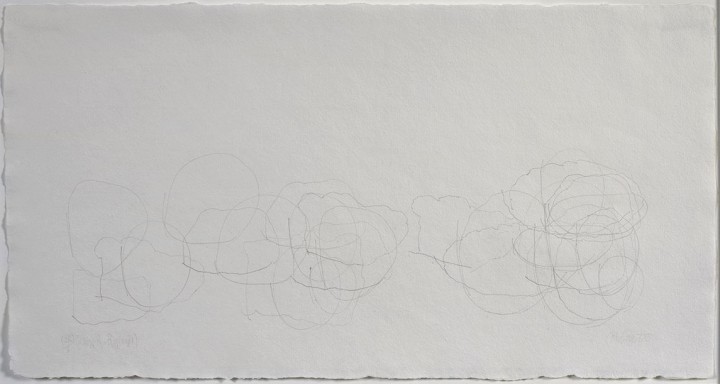

Figure 1. John Cage, (2 R/1) (Where R=Ryoanji) 7/83, 1983,

Graphite on handmade on Japanese paper, 10 x 19 inches (25.4 x 48.3 cm)

© John Cage Trust

John Cage

by Matthew Bailey

From the mid-1940s until his death in 1992, John Cage explored what he called “chance operations” as a means of avoiding artistic subjectivity in his musical compositions, performances, and visual art. The principles of chance, indeterminacy, and open-endedness were for Cage a way of suppressing artistic authority and intention, amplifying the viewer’s participation in the creation and interpretation of the work of art. These procedures, which hinged on randomness and detachment, followed what he called a “doctrine of nonobstruction,” by which he meant “that I don’t wish to impose my feelings on other people . . . in order to leave those centers free to be centers.” For Cage, all beings in the world were “Buddhas,” each of them at the “center of the universe.”1 Indeed, these principles of Zen—together with Zen Buddhist beliefs in art as a reflection of nature and a transcendent instrument of what Cage called “self-alteration,” or something capable of transforming the mind through contemplation—informed his elegant line drawings.2

(2 R/1) (Where R=Ryoanji) 7/83 (1983; fig. 1) is part of the series Where R=Ryoanji, begun in 1983 and inspired by the Zen arrangement of fifteen rocks in the Ryoanji Garden in Kyoto, Japan.3 Displaying a series of loosely drawn biomorphic forms extending horizontally across the lower half of a sheet of textured handmade Japanese paper, the drawing represents not so much the rocks themselves as it does chance in the process of unfolding across an empty page. Running from more discrete spherical forms on the left to a jumbled accumulation of organic circular scribbles on the right, Cage’s meandering contour lines fluctuate between light and heavy, as well as between accidental and more decisive marks. These forms were obtained by tracing around fifteen randomly chosen stones, each corresponding to one of the rocks in the Ryoanji Garden. The number of lines drawn is indicated in the equation in the title, in which 2R denotes that the artist doubled the number of rocks to arrive at the thirty lines employed in the composition. To arrive at this formula, Cage turned to the I Ching, or ancient Chinese Book of Changes, which had served as a major influence on his systematic approach to chance since his first exposure to the text in 1951. The I Ching advises using a divinatory method of prediction based on coin tossing to select from a diagram of possibilities, a practice in which Cage first engaged to determine musical compositions. For his Ryoanji series, he similarly tossed a coin to choose randomly from a preset chart of various elements, including the stones he traced, the number of lines drawn, the position and number of shapes, and the types of pencils used.

While reflecting the apparent randomness of nature through his arbitrary methods, Cage continued to rely on a set of predetermined formulas structuring his use of chance. Though seemingly paradoxical, this system reflected his belief in the initial act of composition—meaning, in this case, the establishment of rules and formulas—as a means not of maintaining artistic control but rather of indicating the “questions that I’ve asked,” with the works themselves serving as “answers that have been given by means of chance operations.”4

Notes

1. John Cage, in Richard Kostelanetz and John Cage, “The Aesthetics of John Cage: A Composite Interview,” Kenyon Review 9 (Autumn 1987): 106.

2. Ibid., 109.

3. My description of Cage’s influences and methods is indebted to David Bernstein and Christopher Hatch, eds., Writing through John Cage’s Music, Poetry and Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 236–38, and Joan Retallack, ed., Musicage: Cage Muses on Words, Art, Music (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press and University Press of New England, 1996), 131–32, 241–43.

4. Cage, in Kostelanetz and Cage, “Aesthetics of John Cage,” 108.

Bios

Matthew Bailey

John Cage

Matthew Bailey on Mel Bochner

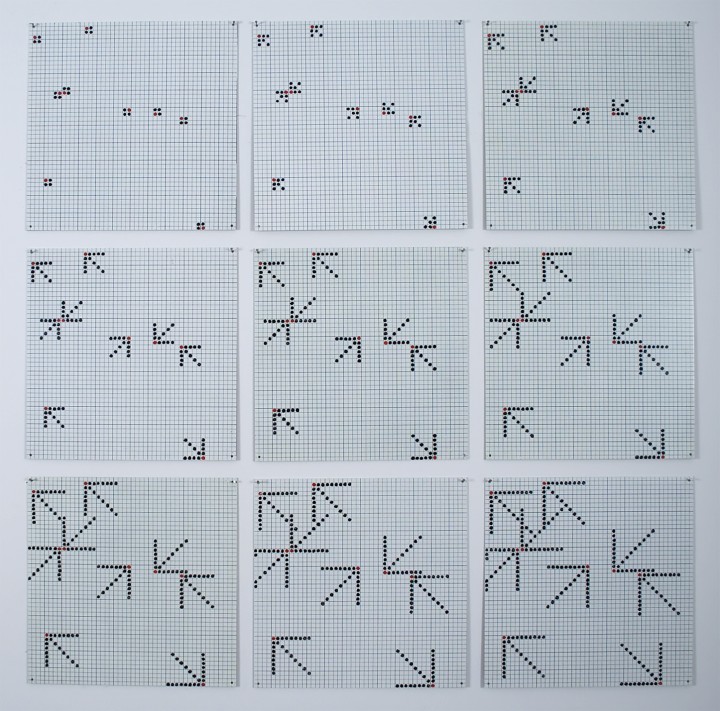

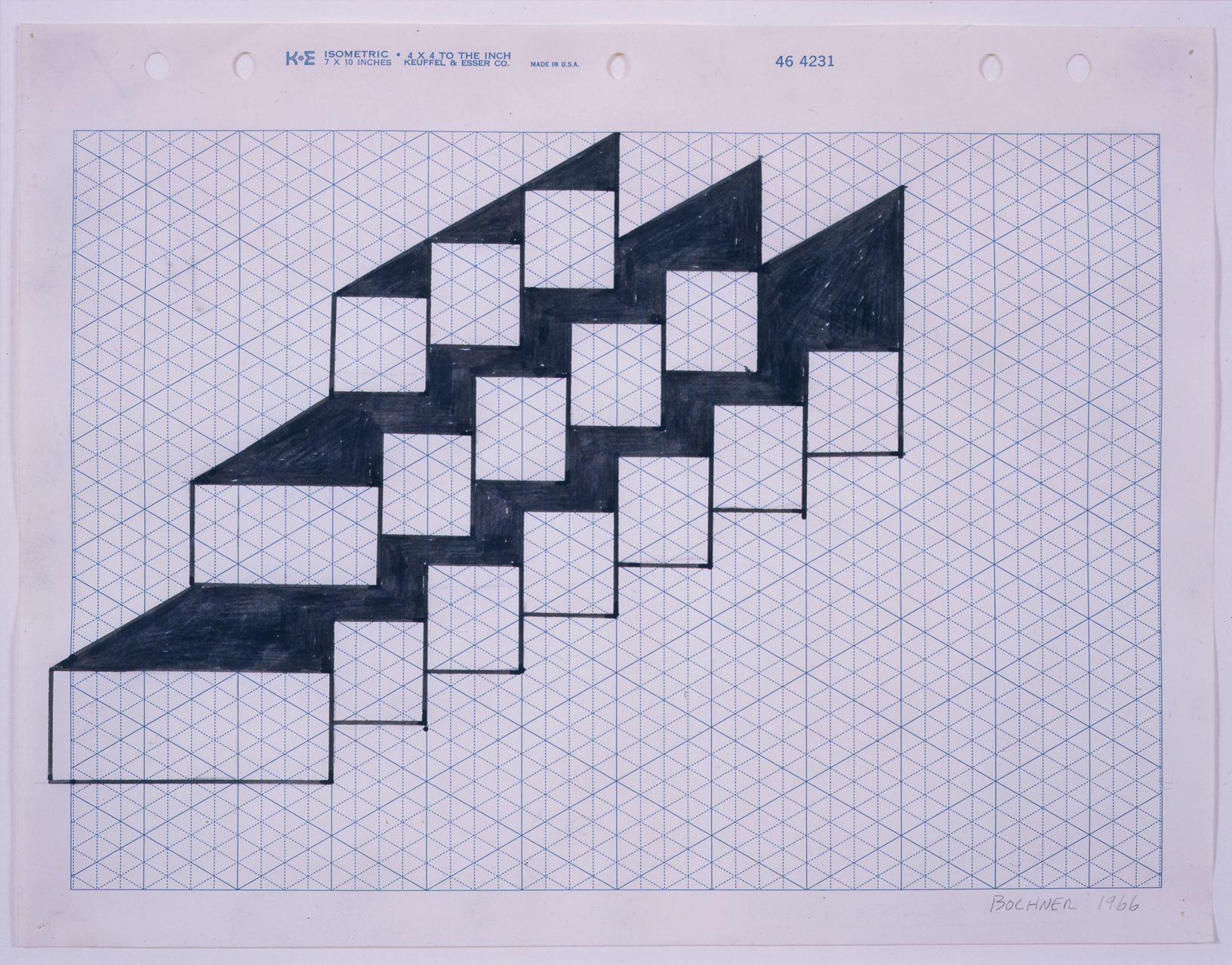

Figure 1. Mel Bochner, Study for Sculpture (3/5/7), 1966

Ink on isometric paper, 8 1/2 x 11 inches (21.6 x 27.9 cm)

© 2012 Mel Bochner

Mel Bochner

by Matthew Bailey

These two drawings by Mel Bochner are meticulously conceived studies for a sculpture and an installation. Representing just one form of the artist’s numerous bodies of works on paper they act as visual articulations of his ideas and serve as proposals with the potential for future realization. Bochner has been a prominent and influential figure in Conceptual art since its inception in the 1960s. In 1966 he organized the exhibition Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed as Art, which announced his belief in the crucial role of drawing as a speculative tool for artists. The show has often been hailed as foundational to Conceptual art because of the way he collected, photocopied, and arranged diagrammatic plans for Minimalist artworks by fellow artists rather than exhibiting the finished objects.1 Bochner regarded drawing as a medium perfectly suited to Conceptual practices because of its flexible and provisional nature, and he wrote extensively about its role in artistic practice. For Bochner, the medium offered “a directness of means with an ease of revision.”2 Drawings could function as “the site of private speculations,” providing “a snapshot of the mind at work.”3 Acting, in his words, as “the residue of thought, the place where the artist formulates, contrives, and discards his ideas,” they “frequently contain the artist’s false starts, meanderings, errors, and incorrect arithmetic, as well as possibilities which might not have occurred to him in any other language.”4

Study for Sculpture (3/5/7) (1966; fig. 1) and Theory of Painting (1–4) (1969; fig. 2) exemplify what Bochner deemed “working drawings,” meaning drawings that “have a purpose other than the merely functional.”5 Unlike traditional sketches for paintings or sculptures, such works served as a field of theoretical experimentation surrounding objects and installations. For all Bochner’s emphasis on the tentative and improvisatory nature of drawing as a site of graphic speculation, however, his drawings are firm, clear, decisive, and ordered, signifying conceptual certainty and visual clarity. This is revealed in his bold, straight lines; carefully crafted forms; attention to shading and color; and concise handwritten notations. The ordered appearance of his drawings was achieved in part through his consistent use of graph paper as a systematic guide that “permits,” as he found, “the easy, and immediate, alignment of thoughts into conventionalized patterns of reading and forming,” a way of making private, abstract meanderings publicly accessible.6 Study for Sculpture employs the structure of graph paper to illustrate an idea for a three-dimensional Minimal sculpture composed of a series of interconnected triangles, drawn with a precise delineation of contours and shading that follows the underlying geometric pattern.

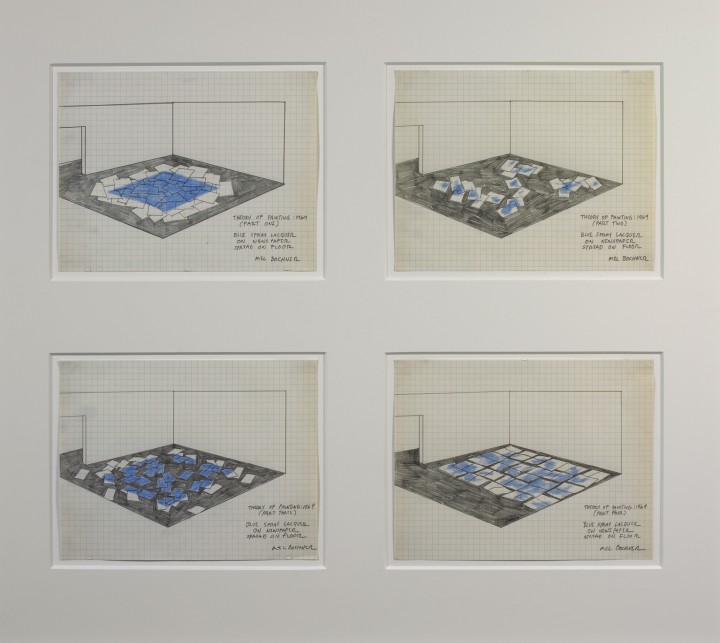

Figure 2. Mel Bochner, Theory of Painting (1-4), 1969

Graphite, ink and crayon on graph paper, 4 sheets, each 8 1/2 x 10 1/2 inches (21.6 x 26.7 cm)

© 2012 Mel Bochner

Works such as Study for Sculpture make apparent the gap between drawing as a two-dimensional space of conceptual speculation and the concrete, three-dimensional artworks that drawings represent, which often remain unrealized. Through his graphic studies, Bochner has frequently examined the parameters and characteristics that define and constitute works of art. This is especially true of Theory of Painting, part of a series of works produced in the 1970s that demonstrate his prolonged investigation of the conventions, languages, and limitations of the medium of painting, in what he called “an analytical attempt to rethink painting’s functions and meanings.”7 The carefully executed study on gridded paper shows four components of a large-scale installation, the materials for which are described in the artist’s notation: “Blue spray lacquer on newspaper spread on floor.” In the first configuration, a blue square is painted on sheets of newspaper clustered on the floor; in the second, the newspapers have been haphazardly scattered, obliterating the square; in the third, the form of a blue square is regained in papers carefully dispersed across the floor; and in the fourth, the papers have been arranged into a rectangular grid, again dissolving the blue square. Playing off Jackson Pollock’s famous drip paintings executed on the ground, Bochner’s work investigates painting as a language of artificial, reproducible, and rearrangeable signs, like the newsprint that acts as the painting’s support. Although the installation depicted has been realized, the sketched plan raises the additional question of whether painting is defined by its physical characteristics, its conceptual aspects, or its spatial locations, with the drawing serving as yet another language through which painting can be materialized and theorized.

Notes

1. The exhibition was at the Visual Arts Gallery, School of Visual Arts, New York. See James Meyer, “The Second Degree: Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed as Art,” in Mel Bochner: Thought Made Visible, 1966–1973, ed. Leslie K. Baier (New Haven, CT: Yale University Art Gallery, 1995), 94–106.

2. Mel Bochner, “Drawing” (1981), in Solar Systems and Rest Rooms: Writings and Interviews, 1965–2007 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 131.

3. Bochner, “Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed As Art” (1977), ibid., 177.

4. Bochner, “Anyone Can Learn to Draw” (1969), ibid., 61.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Bochner, in “How Can You Defend Making Paintings Now: A Conversation between Mel Bochner and James Meyer,” in As Painting: Division and Displacement, ed. Philip Armstrong, Laura Lisbon, and Stephen Melville (Columbus, OH: Wexner Center for the Arts; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 199.

Bios

Matthew Bailey

Mel Bochner