Amanda Beresford on Larry Poons

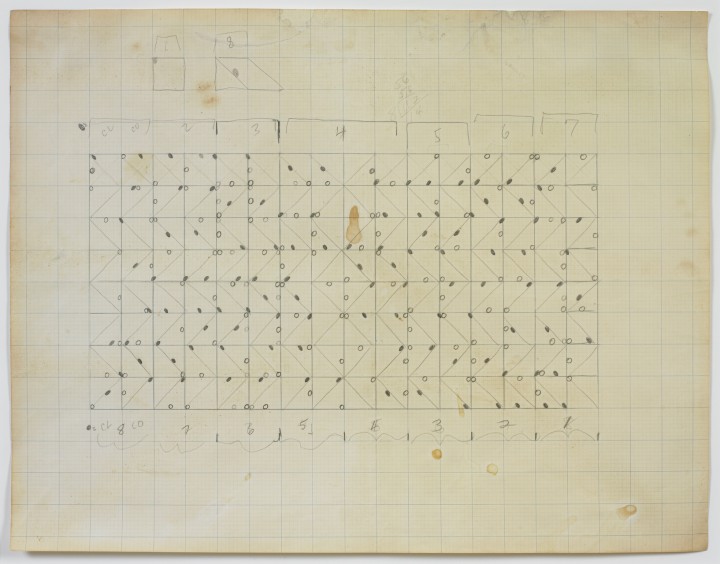

Figure 1. Larry Poons, Untitled, c. 1964

Graphite on graph paper, 17 5/8 x 22 3/8 inches (44.8 x 56.8 cm)

Art © Larry Poons/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Larry Poons

by Amanda Beresford

Larry Poons’s untitled pencil drawing of around 1964 (fig. 1) was made as a study for one of his signature dot paintings of the early 1960s. These paintings consisted of carefully calculated arrangements of dots (and later ellipses) on intensely saturated color fields, the opposing hues of object and ground generating an illusion of movement as well as a colored afterimage in the viewer’s eye. The execution of these works required intensive planning, as this drawing demonstrates.

At art school in the 1950s, Poons was convinced that he could not draw: “I tried. But I found a way—or it found me, I suppose—where if I didn’t look at the paper, and didn’t look at what my hand was doing, and just looked at what I was drawing, I could do it much better than I’d ever done before.”1 He began organizing fields of dots and ellipses on a precise mathematical grid like the one in the present drawing, calculating not only the exact position that the shapes would occupy on the painted canvas but their optical trajectory for the viewer as well. The drawing is squared on graph paper, with the field of the projected painting divided into numbered sections along its upper and lower horizontal axes. Each square is neatly bisected by a diagonal line, alternating in direction with the lines above and below it to create a zigzag pattern. These lines would not be visible in the final painting, but their pattern is indicated by solid elliptical dots. Pointing along the diagonals, the lines of dots add to the directionality of the composition and to its sense of movement. Their shapes are interspersed, seemingly at random, with open circular dots situated on the horizontal and vertical axes of the grid. When transferred to canvas, the precisely positioned dots create the effect of an alternate pattern of movement, generating an optical illusion of space through the interaction of the two shapes, ellipse and circle. The presence of faint pencil lines, as well as smudges and what may be coffee stains on the sheet, reinforces the drawing’s status as a working diagram for a finished painting.

Poons’s work is associated with both 1960s color-field painting and the emergence of Op art, a development focused on color, movement, and the psychology and physiology of perception. He stated that the much-cited afterimage that his paintings produce was at first an unintended effect of his intense palette of brash commercial colors,2 but he was quick to grasp the potential for this work to “explore and extend the range” of optical perception.3 Indeed, the visual experience of his color rhythms has elicited for some viewers an “almost kinesthetic response.”4 Poons has claimed inspiration for his abstract dot paintings from sources as diverse as astronomy—he enjoyed drawing constellations when he was young—and the “crisscrossing” movement of multitudes of pedestrians on Wall Street.5 His plotted diagram is evocative of these sources, offering a look into the artist’s thought process and his meticulous approach to art making.

Notes

1. Larry Poons, in Robert Ayers, “‘There’s No Gap between Seeing and Understanding’: Robert Ayers in Conversation with Larry Poons,” A Sky Filled with Shooting Stars (blog), February 25, 2009, http://www.askyfilledwithshootingstars.com/wordpress/?p=194.html.

2. Henry Geldzahler, “An Interview with Larry Poons, 1963,” in Making It New: Essays, Interviews, and Talks ([New York]: Turtle Point, 1994), 66.

3. James N. Wood, Six Painters (Buffalo, NY: Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, 1971), 11.

4. Ibid, 14.

5. Poons, in Geldzahler, “Interview with Larry Poons,” 67, and in Ayers, “There’s No Gap.”

Bios

Amanda Beresford

Larry Poons