Kristen Gaylord on Robert Ryman

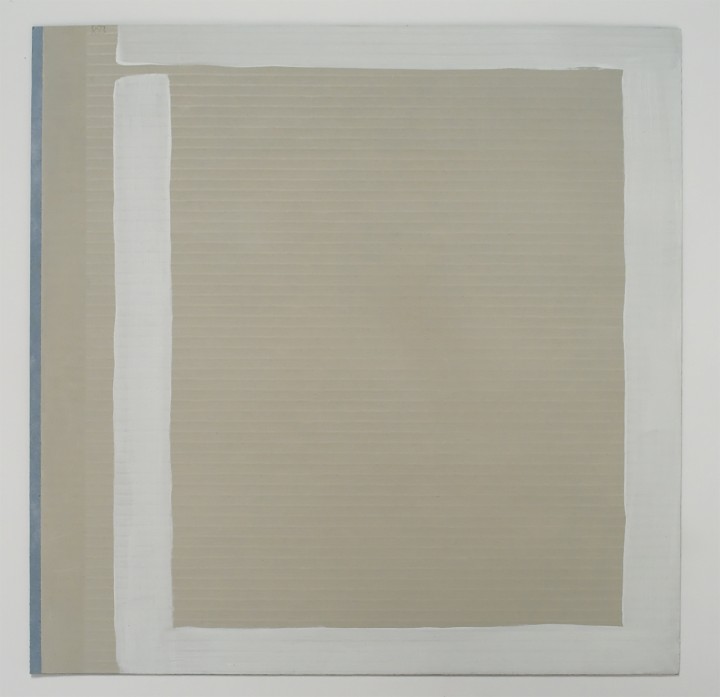

Figure 1. Robert Ryman, PART 12, 1993

Oil paint rolled as primer and brushed on corrugated conservation board, 15 x 15 inches (38.1 x 38.1 cm)

© 2012 Robert Ryman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Robert Ryman

by Kristen Gaylord

Since the beginning of his career in the late 1950s, Robert Ryman has addressed the familiar concerns of modern painting: the monochrome, attention to materiality, autonomous mark making, repetition, and seriality. In an interview with Robert Storr from 1986, Ryman said that art progresses not through organized movements but because “everyone has to take little bites, little pieces of it and work on that.”1 Ryman has narrowly defined his “bites,” often imposing restrictions on his work concerning color, size, shape, subject, material, and technique. As with the formal strictures of a sonnet, however, the systems that he has created have allowed him to realize many subtle variations within categories that might be expected to run dry quickly.2 For example, through his particular study of delineation—his investigation of the relationships of demarcating structures within compositions as well as of the tension between a work and its context—he establishes a seemingly unending stream of generative possibilities.3

By the mid-1990s Ryman had long been an internationally recognized painter. In 1993 he had a retrospective at the Tate Gallery in London that traveled to Madrid and the United States, and it was during this mature period of his career that he created the Part paintings. The lightly inflected oil paint surface of PART 12 (1993; fig. 1), a work from this series, was rolled on and then carefully brushed to build up its velvety texture. The piece is bordered by Ryman’s idiosyncratic brush-wide stroke of white paint, with stripes of blue and light brown paint on the left side, running perpendicular to the corrugated board’s grain. At first it seems that he used the white paint to mark off the space of interest, signaling the boundary of the art piece. But the leftmost section extends the activated field beyond its perceived limit, making clear the insufficiency of the white “frame.” It is almost as if some paint has escaped through the small opening that the artist left in the upper corner, indicating that this white shape is a porous membrane, not a binding perimeter.

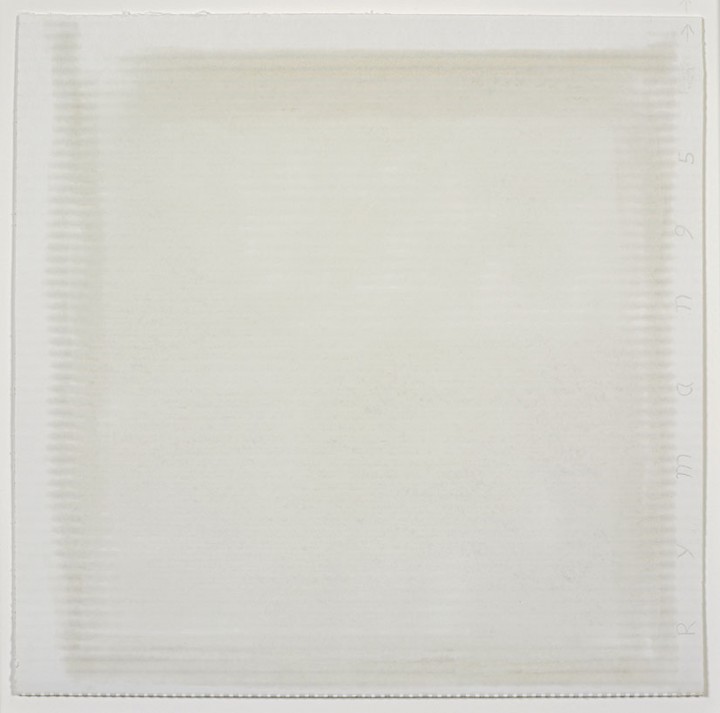

Figure 2. Robert Ryman, Core XII, 1995

Encaustic, graphite, and crayon on corrugated cardboard, 14 x 14 inches (35.6 x 35.6 cm)

© 2012 Robert Ryman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ryman’s installation instructions for the Part paintings are precise: some works are fastened to the wall with nails or screws, others with Elmer’s glue and thumbtacks.4 The scrupulousness of the artist’s directions is undercut by the simplicity of the technology required, which emphasizes both the fragility of the pieces—compounding their structural delicacy with somewhat precarious hanging practices—and the quotidian nature of the materials. Ryman is keenly aware of the importance of art’s display, paying close attention to the wall plane as an integral part of the viewing experience. He has even claimed that he enjoys seeing his paintings in different locations because they “take on a different life each time.”5 With every installation of PART 12, Ryman’s exploration of the bounded expanse of a composition is mirrored anew by the unique tensions between the object and the particular wall behind it—the boundaries created by the artist on the cardboard, the boundary created by the cardboard against the white wall, and the eventual boundary of the wall itself.6

When Ryman created Core XII in 1995 (fig. 2), he was exploring many of the same strategies that he had pursued in PART 12 but through variant iterations. The work—created with encaustic, pencil, and crayon on cardboard—has a similarly open-ended white boundary, defining a nuanced surface space. But the marks are less discrete: the materials are blurred and shift in gradation. Instead of differentiating, they implicate. The effect is unctuous, almost as if the cardboard holds the imprint of oily skin or has yellowed, its distinctions faded by age. The undulating chromatic spectrum of the work is brought to a halt at the meeting of the nuanced surface and the gallery wall, as Ryman contrasts the ambiguousness of his creation and the clinically regulated surface on which it is hung.

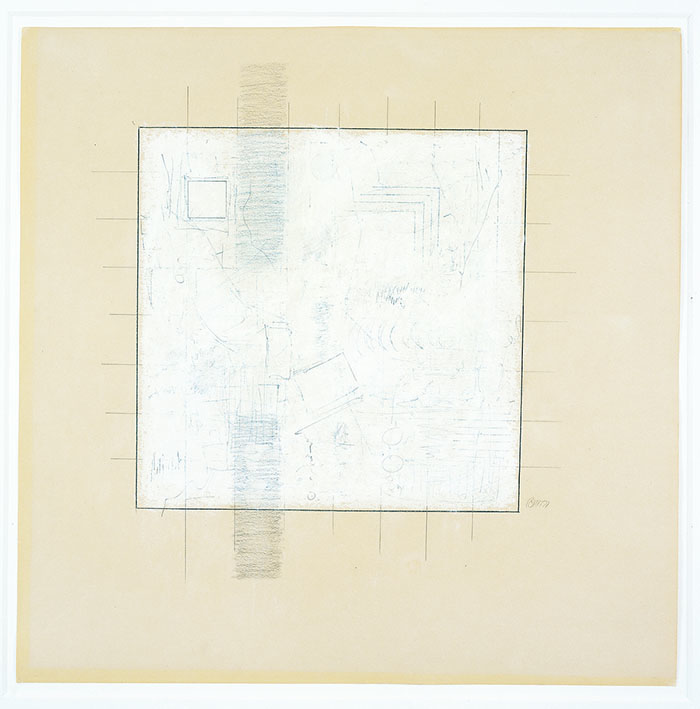

Figure 3. Robert Ryman, Untitled, 1961

Graphite and gouache on paper, 18 3/4 x 18 3/4 inches (47.6 x 47.6 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, 2012

© 2012 Robert Ryman / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ryman’s attentiveness to boundaries has been present in his practice from the beginning. As early as 1961, in his untitled drawing of that year (fig. 3), his interest in delineating space is apparent. The pencil and gouache work at first seems markedly different from the later cardboard pieces since it has neither white outline nor regular surface and is filled with tight and chaotic marks reminiscent of the graffiti-like work of Cy Twombly. The square thick with gouache at the center of the composition is not simply a surface for the pencil marks but is instead intertwined with them, obfuscating some lines and highlighting others; every layer of the process remains visible. Ryman has carefully gridded this central square, with no effort to regulate the stray marks that reach beyond its outline. The white field does not fully extend to the edges of the square but is cushioned by ample room between its outline and the limits of the wove paper. Here the artist makes patently clear the negotiation between the composed arrangement and its exhibition backdrop by exaggerating the border between the two, thereby replicating and complicating the figure-ground relationship.

Ryman’s signature serves as a cartographic key to all these works. Instead of following the convention of signing “over” a painting, his autograph is site-specific, transforming itself into an integral component of each composition. PART 12 includes a reticent “R93” inscribed at the top left, Core XII features a bold “Ryman 95” along the right edge, and the untitled drawing contains initials discreetly tucked to one side of the central square. These signatures work within or push against the artist’s delineations and borders. Ryman creates boundaries only to complicate them; he marks off spaces to highlight the arbitrariness of the markings. This process of careful circumscription undergirds the entirety of his practice, which continues as a systematic exploration of the consequences of even the lightest mark.

Notes

1. Robert Ryman, interviewed by Robert Storr (October 17, 1986), in Abstrakte Malerei aus Amerika und Europa / Abstract Painting of America and Europe, ed. Rosemarie Schwarzwalder (Vienna: Galerie nächst St. Stephan; Klagenfurt, Austria: Ritter, 1988), 213.

2. As Suzanne Hudson writes, “Ryman excises variables to allow for subtle modifications and shifts of emphasis—as given, for instance, by the choice of matte or glossy paint, a flat or rounded brush, a canvas or a linen support of differing weight, grain, tooth, and absorbency—and fosters innovations from work to work or even across the zones of a single painting.” Suzanne Hudson, Robert Ryman: Used Paint (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), 107.

3. For more on Ryman’s interest in the painting’s edge, see Volker Adolphs, “Boundary” (2000), in Robert Ryman: Critical Texts since 1967, ed. Vittorio Colaizzi and Karsten Schubert (London: Ridinghouse, 2009), 331–34.

4. “Installation Information for Robert Ryman ‘Part Paintings,’” Pace Gallery; courtesy the aboutdrawing.org archives.

5. Ryman, interviewed by Storr, 217.

6. Because of its fragility, this work is now displayed in a frame instead of directly on the wall as Ryman originally intended.

Bios

Kristen Gaylord

Robert Ryman