Amanda Beresford on Keith Sonnier

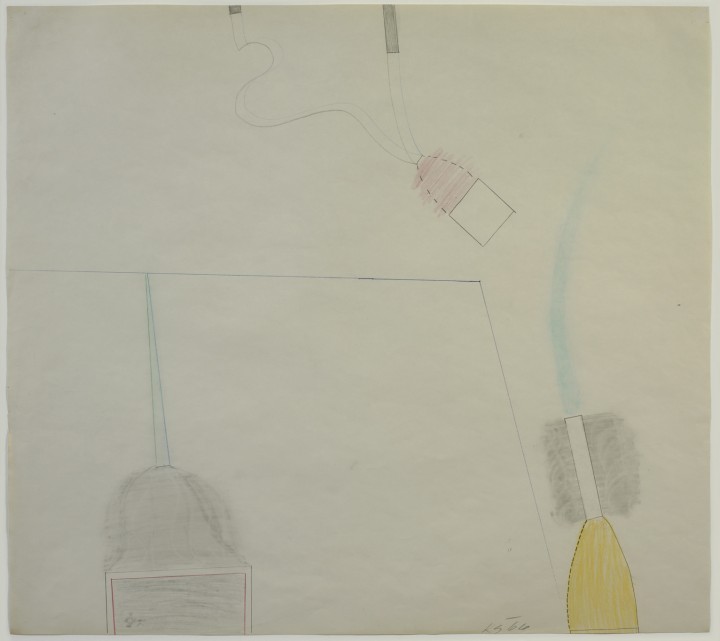

Figure 1. Keith Sonnier, Early Rutgers Drawing, 1966

Ink, graphite, and colored pencil on paper, 20 x 22 1/2 inches (50.8 x 57.2 cm)

© 2012 Keith Sonnier / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Keith Sonnier

by Amanda Beresford

Keith Sonnier’s Early Rutgers Drawing (1966; fig. 1) dates from the period when the artist was studying with Robert Morris on a graduate teaching fellowship at Rutgers University. He was part of a group of artists whose work was later labeled Postminimal. The term relates to various art practices that emerged in the mid-1960s and were characterized by an irreverent attitude that questioned not only traditional “high art” categories and materials but also cerebral Minimal orthodoxy. Sonnier—together with Richard Serra, Bruce Nauman, Eva Hesse, and other like-minded artists—worked with industrial materials such as felt, fiberglass, plastics, and in Sonnier’s case, lightbulbs and neon tubing. These artists introduced what Robert Pincus-Witten called “a new sensibility” into the art world, rejecting the Minimal credo that eschewed subject matter and emotional content by creating works that incorporated references to popular culture and invited the viewer to interact.1

By the late 1960s Sonnier had gained recognition for his playfully exuberant “drawings with light”—sculptural installations using neon tubes and other industrial materials suffused with sensuous color—but conventional drawing on paper is not so readily associated with his practice. This early example is a revealing document of his thinking during a particularly formative year.2 The sheet is a diagram for a light installation using colored lamps, but it betrays a playful subjectivity foreign to most Minimal artists’ drawings of the same period. Using colored pencils and graphite, Sonnier depicted three light fixtures of different types and colors, suspended in an undefined space: a red tulip-shaped fixture with a white collar; a yellow tulip-shaped fixture without a collar; and a gray fixture with a wide rectangular mouth, possibly a floodlight. All three are connected to what may be power cords, tubes, or something more atmospheric, such as air or beams of light. The spatial relationships among the drawing’s elements are ambiguous, however; it is not clear whether we are looking down on the installation from above or up at it from below. The red light apparently has a double tubing, and its serpentine curves inject a sensuous vivacity into the composition. The yellow lamp is positioned at the end of a shallow blue arc, and the gray fixture is either suspended by a straight blue component from an obliquely angled frame, indicated by a simple pencil line, or possibly sitting on the floor. (Sonnier began to experiment with low, floor-based assemblages around this time.)

Although this drawing dates from before Sonnier began using neon in 1967, it demonstrates an engagement with the luminosity of the colored lamps and the nature of light as it permeates space. The colored-pencil shading on the red fixture spills over its outline, suggesting the diffusion of its radiance. The yellow lamp’s blue cord lacks an outline, also suggesting a diffuse radiance, and fades away toward the upper right corner. It is connected to a white section of tubing shown against a gray shaded background; this section appears to radiate darkness, in a negative impression of the preceding effect. A subtle light surrounds the gray fixture, providing a fugitive sense of volume; a thin red line emphasizes the lamp mouth’s inner border. Reflecting on his methods of working with color, Sonnier spoke in 2006 of learning “to treat color as volume” and to exploit its psychological use. This drawing represents an early gesture in this direction.3

Sonnier’s attention to power cords and fixtures and his decision to allow them to become part of the installation rather than hiding them prefigure his readiness in later installations to expose “the mechanical underpinnings” of his works of art.4 The slightly awkward draftsmanship and the sense of rapid execution are characteristic of what Richard Kalina calls his early work’s “brashness” and “offhanded” quality.5 Sonnier was already seeking alternatives to the materials and methods of “high” modernism, a practice that he would take to extremes in his future work with neon, video, and all manner of unconventional and everyday substances, including foam rubber, latex, mirrors, and sailcloth, each “deliberately chosen to psychologically evoke certain kinds of feelings” (although he did not say what those feelings are).6

Another tendency that this drawing forecasts is the theatricality of much of Sonnier’s subsequent work. Critics have commented on the self-consciously dramatic presentation of some of his installations, the dance of the colored gases in their neon tubes, and their deliberate engagement with the spectator. The artist himself, in a recent interview, compares his work to a theater set and the act of making it to the experience of acting in a play.7 Sonnier, like Picasso, may see himself as an actor in the drama of his own art making, but in this drawing he functions more as a playwright or director, asking each of the three lamps to assert its individual character and perhaps inviting the audience to engage with his playful blueprint for experimentation in a new medium.

Notes

1. Robert Pincus-Witten, Postminimalism (New York: Out of London, 1977), 34.

2. “Drawing with Light” is the title of an article on Sonnier by Richard Kalina in Art in America 92 (April 2004): 114–19. In 1966, the year this drawing was made, Sonnier’s work was included in Lucy Lippard’s Eccentric Abstraction, a seminal exhibition for Postminimal art.

3. Keith Sonnier, in Patricia Rosoff, “Electrifying the Inert: A Conversation with Keith Sonnier,” Sculpture 25, no. 1 (2006): 57.

4. Kalina, “Drawing with Light,” 116.

5. Ibid., 116, 119.

6. Keith Sonnier, in Max Blagg, “Keith Sonnier” (interview), Interviewmagazine.com, May 2012, http://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/keith-sonnier/.

7. Ibid.

Bios

Amanda Beresford

Keith Sonnier