Matthew Bailey on John Cage

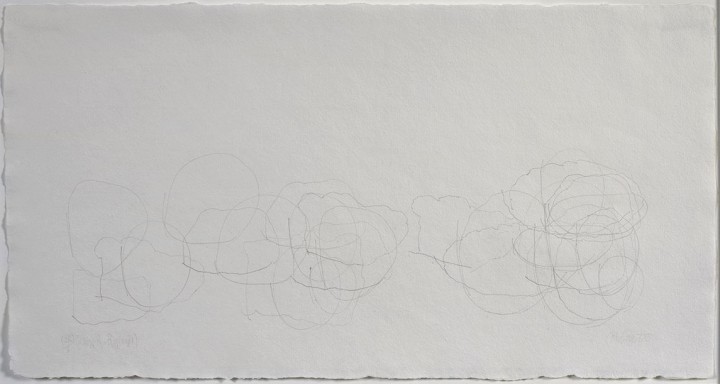

Figure 1. John Cage, (2 R/1) (Where R=Ryoanji) 7/83, 1983,

Graphite on handmade on Japanese paper, 10 x 19 inches (25.4 x 48.3 cm)

© John Cage Trust

John Cage

by Matthew Bailey

From the mid-1940s until his death in 1992, John Cage explored what he called “chance operations” as a means of avoiding artistic subjectivity in his musical compositions, performances, and visual art. The principles of chance, indeterminacy, and open-endedness were for Cage a way of suppressing artistic authority and intention, amplifying the viewer’s participation in the creation and interpretation of the work of art. These procedures, which hinged on randomness and detachment, followed what he called a “doctrine of nonobstruction,” by which he meant “that I don’t wish to impose my feelings on other people . . . in order to leave those centers free to be centers.” For Cage, all beings in the world were “Buddhas,” each of them at the “center of the universe.”1 Indeed, these principles of Zen—together with Zen Buddhist beliefs in art as a reflection of nature and a transcendent instrument of what Cage called “self-alteration,” or something capable of transforming the mind through contemplation—informed his elegant line drawings.2

(2 R/1) (Where R=Ryoanji) 7/83 (1983; fig. 1) is part of the series Where R=Ryoanji, begun in 1983 and inspired by the Zen arrangement of fifteen rocks in the Ryoanji Garden in Kyoto, Japan.3 Displaying a series of loosely drawn biomorphic forms extending horizontally across the lower half of a sheet of textured handmade Japanese paper, the drawing represents not so much the rocks themselves as it does chance in the process of unfolding across an empty page. Running from more discrete spherical forms on the left to a jumbled accumulation of organic circular scribbles on the right, Cage’s meandering contour lines fluctuate between light and heavy, as well as between accidental and more decisive marks. These forms were obtained by tracing around fifteen randomly chosen stones, each corresponding to one of the rocks in the Ryoanji Garden. The number of lines drawn is indicated in the equation in the title, in which 2R denotes that the artist doubled the number of rocks to arrive at the thirty lines employed in the composition. To arrive at this formula, Cage turned to the I Ching, or ancient Chinese Book of Changes, which had served as a major influence on his systematic approach to chance since his first exposure to the text in 1951. The I Ching advises using a divinatory method of prediction based on coin tossing to select from a diagram of possibilities, a practice in which Cage first engaged to determine musical compositions. For his Ryoanji series, he similarly tossed a coin to choose randomly from a preset chart of various elements, including the stones he traced, the number of lines drawn, the position and number of shapes, and the types of pencils used.

While reflecting the apparent randomness of nature through his arbitrary methods, Cage continued to rely on a set of predetermined formulas structuring his use of chance. Though seemingly paradoxical, this system reflected his belief in the initial act of composition—meaning, in this case, the establishment of rules and formulas—as a means not of maintaining artistic control but rather of indicating the “questions that I’ve asked,” with the works themselves serving as “answers that have been given by means of chance operations.”4

Notes

1. John Cage, in Richard Kostelanetz and John Cage, “The Aesthetics of John Cage: A Composite Interview,” Kenyon Review 9 (Autumn 1987): 106.

2. Ibid., 109.

3. My description of Cage’s influences and methods is indebted to David Bernstein and Christopher Hatch, eds., Writing through John Cage’s Music, Poetry and Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 236–38, and Joan Retallack, ed., Musicage: Cage Muses on Words, Art, Music (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press and University Press of New England, 1996), 131–32, 241–43.

4. Cage, in Kostelanetz and Cage, “Aesthetics of John Cage,” 108.

Bios

Matthew Bailey

John Cage