Jennifer Padgett on Robert Smithson

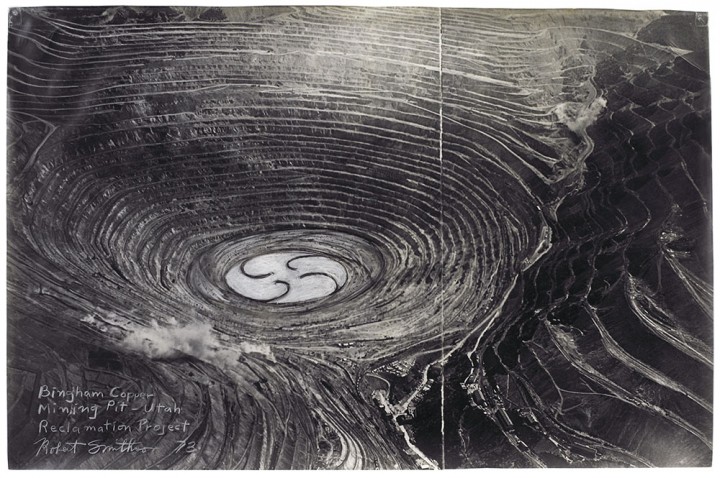

Figure 1. Robert Smithson, Bingham Copper Mining Pit – Utah Reclamation Project, 1973

Wax pencil and tape on plastic overlay on photograph, 20 x 30 inches (50.8 x 76.2 cm)

Art © Estate of Robert Smithson/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Robert Smithson

by Jennifer Padgett

Robert Smithson combined drawing with photography in Bingham Copper Mining Pit—Utah Reclamation Project (1973; fig. 1), a presentation work that is part of his Reclamation series. He began with a photograph of a specific site—the Bingham Copper Mining Pit in Utah—and then superimposed his drawing on it by placing a transparent plastic overlay on the image and sketching his proposed intervention on the surface in white wax and black pencil. The object is engaging; employing both preexisting and imagined forms, it invites the viewer to envision the site transformed by the installation. Smithson’s design features a revolving disk with four evenly spaced hooklike lines on a white ground; placed at the bottom of the pit, it appears to spiral in a vortex movement toward its center. The composition and detail of the photograph draw the eye to the disk, which is placed at the center of the visual field. The stepped walls of the pit resemble natural forms such as tree rings or the sedimentary layers of earth’s crust, and the sense of scale suggests epic and overwhelming forces at work.

Smithson prepared the drawing-photograph as part of a proposal to the Kennecott Copper Corporation, the owner of the mine, in the hopes of obtaining permission to construct an earthwork at the site. Through his reclamation series, he intended to recover spaces already transformed by human activities such as commercial mining and other destructive industrial processes. He claimed, “One practical solution for the utilization of such devastated places”—including the Bingham Copper Mining Pit—“would be land and water re-cycling in terms of ‘earth art.’”1 This position was characteristic of the Land art movement emerging in the late 1960s and 1970s, in which artists pursued a greater awareness of the environment and the effects of human activity on nature through the construction of site-specific works. Smithson—like his wife, Nancy Holt, and other Land artists—often positioned large-scale works outside the traditional gallery setting, looking to the expanses of the western United States as a terrain rich in sites for massive interventions that would call attention to ecology and natural forces.

The Bingham project was never realized, as the Kennecott Corporation apparently ignored the proposal and Smithson died in an airplane crash later in the year. While the drawing remains as an illustration of an artwork that could have had a transformative effect on an unlikely space, it also exemplifies Smithson’s particular approach to the artistic process. Rather than emphasizing the cultural value of a project or sculpture in material form, he imagined a greater fluidity among the various processes involved in being an artist, making a point of not privileging one category of art production over another according to a traditional hierarchy. The numerous manifestations of a project—in drawing, photography, or site-specific installation—could expand the boundaries of the creative process, as the inclusive work of art is not limited to one object or physical form.2

Figure 2. Robert Smithson, Shed with Asphalt, 1970-71

Graphite on paper, 20 x 25 inches (50.8 x 63.5 cm)

Art © Estate of Robert Smithson/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Smithson’s pencil drawing Shed with Asphalt (1970–71; fig. 2) has no direct correlation to a specific earthwork, yet it relates to other projects in his oeuvre and again illustrates how the artist used various mediums to synthesize the themes that interested him, including entropy and its effects on both natural and man-made elements. Smithson drew the basic form of a four-sided building viewed from the side, with a slight tilt toward the viewer so that the top of the structure is visible. Nebulous forms, representing flowing asphalt, ooze across the roof, out the windows, and onto the ground surrounding the shed. The asphalt is depicted as an entropic force that overwhelms the simple structure. Smithson was attracted to asphalt as a material that was derived from natural sources yet manufactured for use in modern construction. Its viscous quality implies a certain dimension of time in its slow movement across a surface. This drawing is not a naturalistic treatment of the properties of asphalt but instead provides an imaginative view, animated by busy pencil lines.

The drawing somewhat recalls Partially Buried Woodshed (1970), a realized work in which Smithson piled twenty truckloads of earth onto a woodshed until it collapsed. It also references the material used in his Asphalt Rundown (1969), in which he poured a truckload of asphalt down a quarry wall in Rome. By synthesizing elements from these two works in this drawing, Smithson took advantage of the flexibility of the medium as a match for his great capacity for rethinking and expanding upon his ideas.

Notes

1. Robert Smithson, “Untitled, 1971,” in The Writings of Robert Smithson, ed. Nancy Holt (New York: New York University Press, 1979), 220.

2. Jack D. Flam, introduction to Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack D. Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), xviii.

Bios

Jennifer Padgett

Robert Smithson

Jennifer Padgett on Richard Serra

Richard Serra

by Jennifer Padgett

Richard Serra may be best known for his massive sculptures, but drawing is fundamental to his artistic practice. In a 1977 interview he explained: “Drawing is a concentration on an essential activity, and the credibility of the statement is totally within your hands. It’s the most direct, conscious space in which I work. I can observe my process from beginning to end, and at times sustain a continuous concentration. It’s replenishing. It’s one of the few conditions in which I can understand the source of my work.”1

Serra’s drawings take various forms, including large swaths of linen covered entirely in paint stick as well as contour drawings on paper. The drawing Tilted Arc (1986; fig. 1) is a prime example of the latter type, with a rounded outline of thick contoured strokes dominating the pictorial space. The drawing relates to Serra’s sculpture of the same title from 1981, commissioned by the US government’s General Services Administration for Federal Plaza in downtown New York. The sculpture was dismantled and removed from the plaza in 1989, after much controversy and public debate.2 Serra made this drawing during the short period in which the sculpture remained in situ; thus it is not a preparatory work but a study completed afterward. This is typical of the artist’s drawing practice. In a recent interview, he explained: “I’m a model-maker. I make models, then the models are translated, and then, after, I make drawings, which is like a whole autonomous body of work. The drawings and the notations are sometimes a reference to ideas of the sculpture, but they’re not representations to be used to make sculpture from.”3

In the drawing, Serra presents Tilted Arc as a bent quadrilateral form in black lines, appearing to push against the upper edge of the sheet. The original sculpture was a rectangular piece of steel, 120 feet long, 12 feet high, and 2 1/2 inches thick. The drawing suggests the sculpture as seen from a viewpoint closer to one end of the piece, as the right edge appears larger in scale than the left edge, but Serra preempted any further illusionistic reading. Instead of depicting the sculpture in space in a realistic way, he used gestural marks to render his physical experience of the work. The figure oscillates between geometric and organic, graphic and painterly, weighty and floating. The dynamic created by Serra in this drawing is related to the effect that he pursues in his sculptural work. He is interested in how the experience of viewing a given work unfolds, as the viewer perceives the forms in real time and space from different angles and distances. The physical experience of his sculptural works is a primary concern for Serra, as he believes that direct interaction engenders in the viewer a greater awareness of the work, the surrounding environment, and one’s place within it.

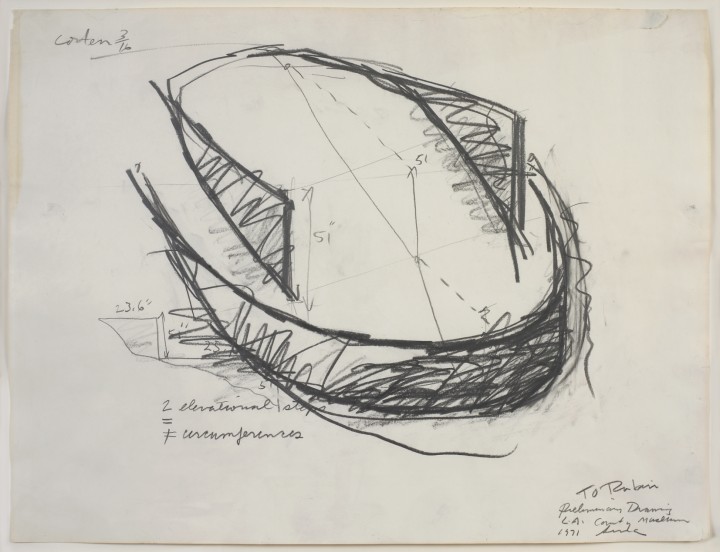

Figure 2. Richard Serra, Untitled (Preliminary Drawing for L.A. County Museum), 1971

Graphite on paper, 17 3/4 x 23 1/3 inches (45.1 x 59.7 cm)

© 2012 Richard Serra / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Untitled (Preliminary Drawing for L.A. County Museum) (1971; fig. 2) is a rare early example of Serra’s use of drawing in a more traditional sense, as a preparatory medium. As the title suggests, he completed the work as a preliminary drawing for an unrealized sculpture intended for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). The subject is rendered in loose freehand lines, without particular attention to accurate illustration. Two arcs compose a loose elliptical formation in the center of the drawing, with notations, diagrammatic marks, and calculations jotted across the page. The inscription in the upper left—“corten”—indicates COR-TEN steel, which is Serra’s preferred material for large-scale sculpture. The representation of space is disorienting, as the elliptical construction seems to sit on a different ground plane from the step marked “23.6″” directly to the left. While Serra could have used such a drawing as a traditional study—a means of working through the construction of the sculpture—Untitled (Preliminary Drawing) is most effective as a presentation drawing, created to convey the basic idea and form of the project to another individual or group, likely one associated with LACMA.

The capacity of drawing to share ideas and communicate with others relates to Serra’s belief that the medium is a form of language. In 1992 he stated: “Drawing to me is a language that allows me to understand the world, an analytical tool. It is a practical means to assign perception to memory. I understand complexities through drawing, it enables me to grasp them.”4 For Serra, drawing provides a realm for thinking through the issues that concern him most in his practice, its immediacy allowing for a conscious and direct interaction with the forms that he creates.

Notes

1. Richard Serra, in Lizzie Borden, “About Drawing: An Interview” (1977), in Richard Serra, Drawing: A Retrospective (Houston: Menil Collection, 2011), 59.

2. See Harriet F. Senie, The Tilted Arc Controversy: Dangerous Precedent? (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

3. “Draw It Black: A Q&A With Richard Serra on His Daring New Retrospective at the Met,” interviewed by Andrew M. Goldstein, Artinfo, April 18, 2011, http://www.artinfo.com/news/story/37489/draw-it-black-a-qa-with-richard-serra-on-his-daring-new-retrospective-at-the-met.

4. Richard Serra, interviewed by Lynne Cooke, May 21, 1992, in Richard Serra: Drawings (London: Serpentine Gallery; Düsseldorf: Richter, 1993), 15.

Bios

Jennifer Padgett

Richard Serra

Jennifer Padgett on Jasper Johns

Figure 1. Jasper Johns, From Untitled Painting, 1964-65

Charcoal, oil, and pastel on paper, 21 7/8 x 33 7/8 inches (55.6 x 86 cm)

Art © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Jasper Johns

by Jennifer Padgett

Jasper Johns’s From Untitled Painting features an imprint of the artist’s face in the center of a sheet of drafting paper, framed by a rectangular outline. The drawing relates to his large untitled polyptych of 1964–65, now in the collection of the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, which includes a similar image of a blurred facial trace. Johns uses a variety of techniques and materials in the painting, including stenciling, the addition of three-dimensional objects such as a broom, and the use of devices to make rainbow-like swipes within several panels. His drawing likewise includes a number of mark-making techniques, in particular imprinting, but it has a more focused and personal quality than the larger work. Although the drawing may be a preparatory study for the painting, it also could have been completed after the execution of the painting, a rather untraditional practice but one that Johns has frequently adopted.1 The completion of highly finished drawings after paintings—what Nan Rosenthal has called “‘postplay’ rather than foreplay”—indicates how thoroughly Johns has integrated a variety of mediums and processes within his overall practice.2 By taking one element of a painting and recasting it in a different medium—subtly modulated charcoal marks on paper—he meditated on the potential of the techniques available.

Imprints of body parts, such as the face or hands, appear in many of Johns’s paintings and drawings. He explores the potential of the body to create marks through direct contact with the canvas or paper, leaving a trace of its presence on the surface. Johns appears to have created the indexical mark of the face in From Untitled Painting by placing one side of his face on the paper and then turning or rolling it to imprint the other side. He likely covered his face with a light layer of baby oil before making the imprint and then rubbed charcoal across the sheet afterward to bring forth the traces of oil in darker tones.3

The application of charcoal in From Untitled Painting makes the image of the face visible, yet the unevenness of the sweeping strokes results in a highly illegible surface. While a solid rectangular outline cropped tightly around the imprint focuses the viewer’s gaze on the central section of the paper, the image in the circumscribed area remains muddled and ambiguous. The imprint of the face may read as a flayed skin stretched across the two-dimensional surface or, alternatively, as two separate faces meeting in the center. The former possibility evokes a visceral response to the flattened human form, while the latter insinuates a sense of intimacy and closeness. In both readings there is a strong appeal to the tactile sensibility of the viewer, with directness and touch as primary concerns.

Johns has engaged with the link between touching and looking throughout his long career, and he admires this quality in the works of other artists. For example, he was taken with a scene of bathers by Paul Cézanne because it “makes looking equivalent to touching.”4 The direct trace of the body through the imprint serves to develop this theme in Johns’s work, as the image registers the process of its making and the physical action involved. At the time this drawing was made, the body imprint also provided Johns with a means of establishing a personal statement in visual terms that departed from the model of Abstract Expressionist gesture, which had become moribund by the 1960s. The imprint of the artist’s face in From Untitled Painting, both revealed and obscured by a flurry of charcoal strokes, asserts his physical engagement with the work. Johns did not subvert the notion of the artist’s hand so much as literalize it by bluntly inserting his own body into the work, leaving a ghostly trace of his presence.

Notes

1. In an interview from 1989, Johns claimed that most of his finished drawings were made after the paintings of the same subject. Johns, in Ruth Fine and Nan Rosenthal, “Interview with Jasper Johns” (June 22, 1989), in The Drawings of Jasper Johns, by Nan Rosenthal et al. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1990), 72.

2. Nan Rosenthal, “Drawing as Rereading,” ibid., 15.

3. He used this process in the series Studies for Skin, completed in 1962 as preparatory drawings for a sculptural work that was never executed. Jeffrey S. Weiss, “Painting Bitten by a Man,” in Jasper Johns: An Allegory of Painting, 1955–1965 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2007), 13.

4. Grace Glueck, “The Twentieth-Century Artists Most Admired by Other Artists,” Art News 76 (November 1977): 87, quoted in Rosenthal et al., Drawings of Jasper Johns, 272.

Bios

Jasper Johns

Jennifer Padgett

Jennifer Padgett on Nancy Holt

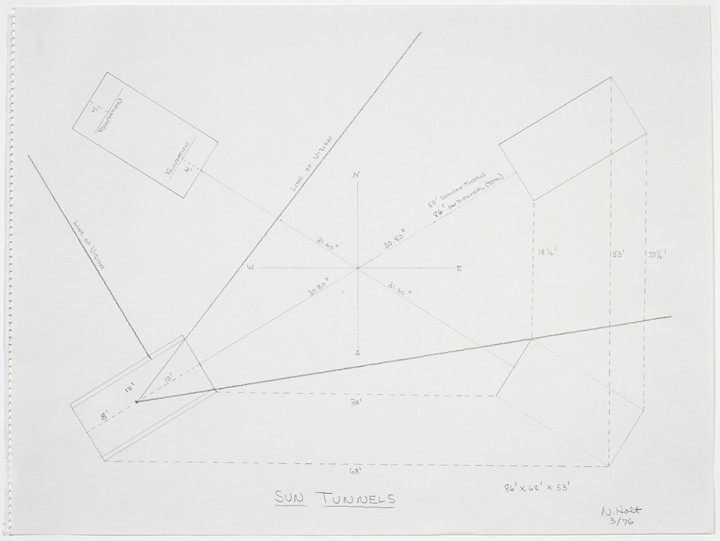

Figure 1. Nancy Holt, Study for Sun Tunnels, 1976

Graphite and crayon on paper, 18 x 24 inches (45.7 x 61 cm)

Art © Nancy Holt/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Nancy Holt

by Jennifer Padgett

Nancy Holt completed the drawing Study for Sun Tunnels (1976) during preparatory work for her site-specific installation Sun Tunnels (1973–76; fig. 1) in an area of Utah that is part of the Great Basin Desert. For the large-scale sculptural work, Holt placed four hollow concrete cylinders in an X-shaped arrangement, carefully oriented to create specific lines of vision that relate to both the surrounding desert land and larger astrological patterns. Holt—a central participant in the Land art movement that emerged in the late 1960s, which included artists such as Robert Smithson, Walter De Maria, and Michael Heizer—aimed to stimulate a greater awareness of the natural environment, and of human interaction with it, by using her work to focus selectively on elements such as the sun, moon, and stars. Sun Tunnels, like many other works of Land art, is a sculptural installation on a monumental scale that affects the viewer’s perception of both time and space.

On the summer and winter solstices, sight lines through the Sun Tunnels cylinders align with the position of the sun on the horizon, highlighting the cyclical quality of the solar year. The upper half of each tunnel is drilled with a series of variably sized holes, which allow natural light to stream into the interior. The holes were designed to correspond to the position and relative magnitude of the stars in a particular constellation, and their configuration is based on a complex calculation determined through the use of a helioscope, an instrument employed to observe the sun.1 The position and design of the cylinders required meticulous attention to astrological and geological conditions, and Holt collaborated extensively on the execution of the work. She worked with engineers, an astronomer, an astrophysicist, ditch diggers, and concrete pipe company workers, among many others, as the design, fabrication, and placement of the four cylinders—each weighing twenty-two tons—in a remote stretch of the Utah desert required considerable labor and logistical support.2

Holt’s construction drawing presents an abstracted vision of the sculpture, not re-creating the experience of viewing it but instead simplifying the sculptural installation into austere diagrammatic forms. In doing so, the drawing represents with mathematical precision the relationships among the work’s elements. The tunnels are indicated by four rectangles, viewed schematically from above as in an architectural plan. The viewer’s potential interactions with the objects are indicated by three straight lines, each marked “Line of vision,” projecting from the tunnel in the lower left corner of the sheet. She also noted the distances between the tunnels with dotted lines. Further expanding the context in which the tunnels are oriented, Holt registered their placement with respect to the cardinal directions, with two intersecting lines at the center of the drawing forming a compass marked by letters for north, south, east, and west at the respective endpoints. Two angled lines intersect this compass, indicating the axes along which the tunnels are placed; each line is marked with a notation of its degree of rotation from the cardinal axis, either 30.80˚ or 31.60˚.

The construction of the tunnels appears logical and orderly in the drawing, without the tension between man-made elements and nature that is a central concern in Holt’s site-specific work.3 The drawing offers only one view of the sculpture, while the actual experience of Sun Tunnels involves a more complex temporal and spatial process, as an individual can move toward, around, and even inside the giant concrete cylinders. In the presence of the sculptural work, the viewer is drawn into a greater consideration of the dynamic interplay between the tunnel structures and the surrounding landscape.

As diagrams, and as tools for plotting the relationships among various elements, this work and similar drawings were essential to the planning and execution of Holt’s large-scale sculptural installations. Beyond this practical function, the drawing illustrates a vital layer in Holt’s conception of Sun Tunnels and emphasizes the importance of visual and spatial interrelationships within the organizational structure of the piece.

Notes

1. Nancy Holt, “Sun Tunnels,” Artforum 15 (April 1977): 37.

2. Ibid., 33.

3. Alena J. Williams, introduction to Nancy Holt: Sightlines, by Alena J. Williams et al. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 34.

Bios

Nancy Holt

Jennifer Padgett

Jennifer Padgett on Eva Hesse

Figure 1. Eva Hesse, Untitled, 1963-64

Collage, gouache, watercolor, and ink on paper, 22 x 30 inches (55.9 x 76.2 cm)

© The Estate of Eva Hesse, Hauser & Wirth Zürich London

Eva Hesse

by Jennifer Padgett

Eva Hesse was attracted to the medium of drawing throughout her career, regarding it as more flexible and immediate than painting and thus better suited for developing her own artistic approach. As an artist working in a Postminimal or antiformalist mode, she was interested in nontraditional materials, references to the body, and a rejection of the formal conventions associated with high modernist artistic practice. Hesse’s works in latex, cheesecloth, resin, and other unusual materials challenged the established standards of sculptural form; these objects connect to her drawing in their mutual pursuit of new forms that could be simultaneously ordered and chaotic, rational and irrational. In her diary she advocated the process of drawing as a means of exploring nascent concepts, writing: “If drawing gives some pleasure—some satisfaction—do it. Go ahead. It also might lead to a way other than painting, or at least painting in oil. First feel sure of an idea, then the execution will be easier.”1 This self-motivational statement expresses both permission and support, positioning drawing as an outlet for working through ideas and as a means of finding alternative methods in artistic practice. For Hesse, drawing provided ease of execution and less material resistance than working in painting or sculpture, allowing her greater freedom for creative development.

In her drawings Hesse pursued a variety of serial techniques, employing repetition as a formal and conceptual strategy, as many Minimal and Conceptual artists did during the 1960s. Her untitled drawing of 1963–64 (fig. 1) features a complex arrangement of repeating shapes. This repetition serves to emphasize the idea of accumulation, as basic shapes are reduced and repeated to allow a consideration of the relationships between them.2 Unlike the rational and impersonal serial strategies of some Minimal artists, however, Hesse’s use of accumulation and repetition takes on a more introspective, even obsessive quality.

The composition can be divided loosely into three main segments. The section on the left comprises several vertical strips of shapes such as cubes and circles stacked one atop the other. Some of the strips are relatively uniform, such as the stretch of orange rectangles near the left edge, while others are more varied. The roughly rectangular arrangement in the center is distinguished by areas of black and two arrows that appear to point toward the top edge of the sheet. On the right, a large swath of yellow, hazily outlined with gray and containing geometric shapes such as an X and a circle set into boxlike forms, dominates the grouping, with two rows of gray rectangles lined up underneath the larger shape.

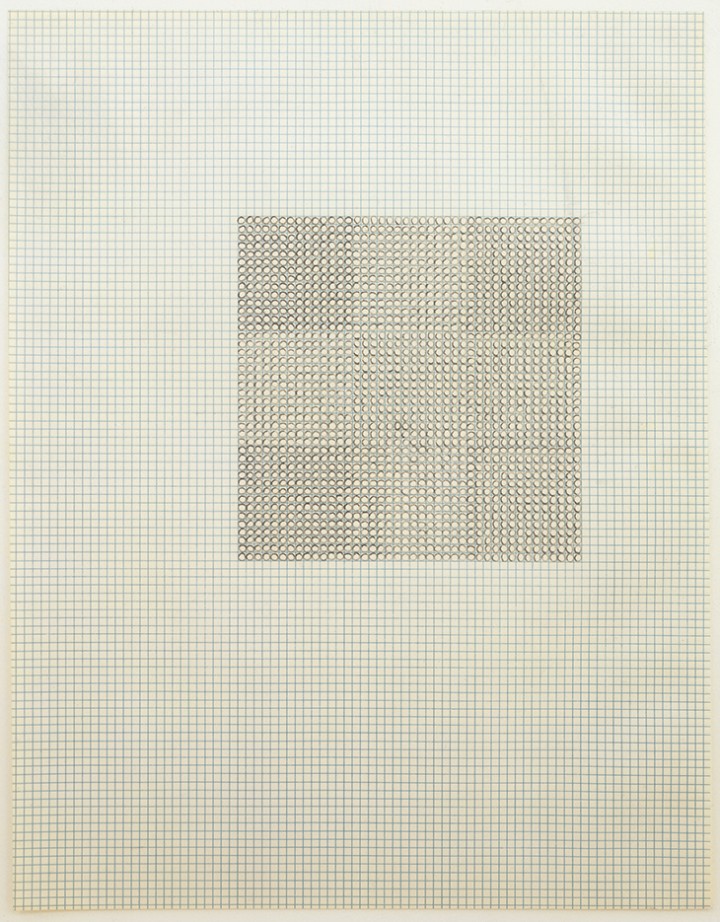

Figure 2. Eva Hesse, Untitled, 1967

Ink on graph paper, 11 x 8 1/2 inches (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

© The Estate of Eva Hesse, Hauser & Wirth Zürich London

The image imparts a chaotic sense of space and an energetic quality, as the accumulations of recurring forms build upon one another and interrelate in a play of abstract shapes. This feeling of energy is emphasized by the lively contrast of colors and the dynamic tilt of the grouped vertical forms, which add a frenetic quality to the work as they veer toward the upper left corner of the sheet. Hesse completed several similar drawings, and together they illustrate her interest in repetition—both of forms and of working methods. She believed that “repetition does enlarge or increase or exaggerate an idea or purpose in a statement” and that the statement being developed could express an interior condition or feeling.3 The repeated forms in the untitled drawing suggest the possibility of an ordered system, but because they never quite cohere or fall into a rational arrangement, they seem also to express a sense of absurdity or confusion.

Hesse’s continued interest in repetition is made manifest in her drawing of 1967 (fig. 2), one of a series of related grid drawings. On blue graph paper, she drew a square composed of black ink circles, each bounded by the borders of a single square of the graph. She varied the pressure of the pen to create variations in tone, and a cross seems to appear from the pattern of lighter circles within the larger square. The resulting work is a combination of ready-made, predetermined elements—the graph paper and its individual units—and the work of the hand, the imprecise circle marks of the pen. The grid seems to impose a certain logic, but the slight variations between the circles and the seemingly arbitrary location of the square on the sheet (slightly off-center) indicate resistance to a strictly deterministic system. Hesse used the grid, a strategy that had become a mainstay of Minimal practice by the 1960s, yet subverted it to serve her own purposes.4 She reasserted the hand of the artist and, with it, variation and unpredictability.

Notes

1. Eva Hesse, quoted in Lucy R. Lippard, Eva Hesse (New York: New York University Press, 1976), 32.

2. On Hesse and the use of repetition as a “way to engage looking,” see Briony Fer, The Infinite Line: Re-Making Art after Modernism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 8, 60.

3. Lippard, Eva Hesse, 5.

4. Elisabeth Sussman, ed., Eva Hesse (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2002), 198.

Bios

Eva Hesse

Jennifer Padgett

Jennifer Padgett on Carl Andre

Figure 1. Carl Andre, Subfield, 1966

Ceramic magnets, 84 units, rectangle 6 x 14, 1/2 x 18 x 13 5/8 inches (1.3 x 45.7 x 34.6 cm)

Art © Carl Andre/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Carl Andre

by Jennifer Padgett

Carl Andre’s work in drawing is intrinsically linked to his sculptural objects, although the artist has resisted the notion that preparatory drawing is important as a conceptual exercise in the creation of three-dimensional objects.1 As one of the leading figures of Minimal art, Andre has continually emphasized the material object and its presence in space over any kind of concept or “idea” generated by the artist and meant to be conveyed through the work. In his floor pieces and other sculptural works, he has focused on viewers’ experiences and their movements in relation to the work. He has described his approach as materialist as opposed to conceptual, claiming, “I am certainly no kind of conceptual artist because the physical existence of my work cannot be separated from the idea of it.”2 Andre believes that a work of art should be derived from the specific properties of the materials employed and that this is best achieved through direct physical interaction rather than by plotting out preconceived ideas through drawing.

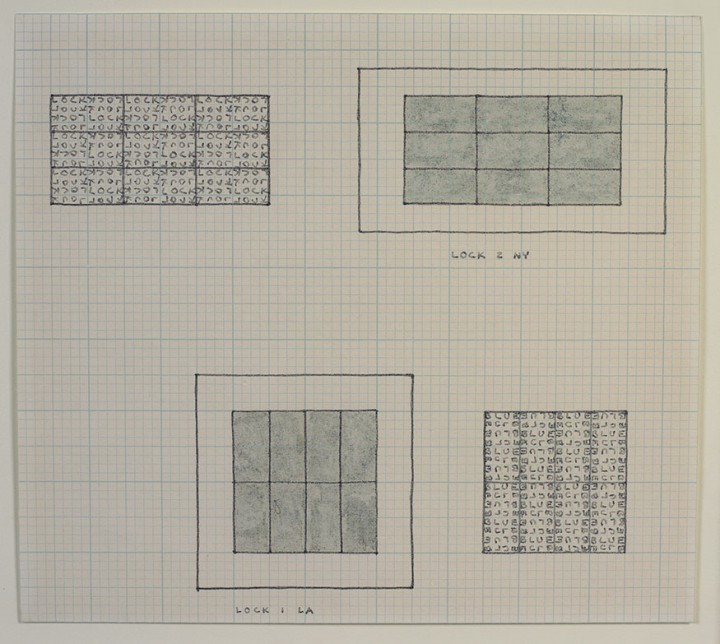

Figure 2. Carl Andre, Blue Lock, 1966

Colored ink and felt-tip pen on graph paper, 8 3/4 x 9 3/4 inches (22.2 x 24.8 cm)

Gift of Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Art © Carl Andre/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

The drawing Blue Lock (1966; fig. 2) is therefore connected to Andre’s sculptural work but also reflects a calculated employment of the specific properties of drawing as a medium. The four rectangular configurations depicted here in colored ink and felt-tip pen on graph paper relate to the sculptures Blue Lock Trial (1966) and Blue Lock (1967).3 Andre’s Lock sculptures were constructed of chipboard, a material selected out of economic necessity and painted blue to suggest a steel surface.4 Each of the rectangular arrangements in the upper half of the drawing comprises a series of smaller rectangles, arranged three across by three down and aligned with the overall grid of the paper although slightly offset from the preprinted pattern. These drawn rectangles directly reference Blue Lock Trial, as indicated by the notation below: “LOCK 2 NY.” The two configurations in the lower half of the sheet are composed of similar rectangular pieces, turned on end and arranged in a pattern of four across by two down, resulting in an overall square. The notation for this pair, “LOCK 1 LA,” links them to Blue Lock, which was commissioned for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s exhibition American Sculpture of the Sixties (1967).

Each individual square making up the rectangle in the upper left contains one of the four letters that spell lock in the square in the lower right corner of the sheet, the letters that spell the word blue are arranged in a similar fashion. These words are oriented in various directions, resulting in a puzzle-like effect. By implying a number of positions from which to read the words, the lettering suggests a turning of the sheet that echoes the movement of a viewer around the sculptural object in space.5 The interlocking word patterns also suggest a kind of interior logic organizing the pieces within the larger shapes. Andre was deeply interested in ordering systems, and in works such as Subfield (1966; fig. 1), he explored how such systems could be intrinsic to the materials used.6 This sculpture consists of eighty-four ceramic magnets, arranged in a rectangular shape and held together by magnetic force upon the proper alignment of their north and south poles. The structure and arrangement of the overall work are thus determined by qualities inherent in the material itself, which suits Andre’s materialist approach. In the drawing Blue Lock, the graph paper supplies the predetermined logic on which the artist builds to suggest a deeper rationale underlying the organization of subparts.

The experience that the drawing offers is distinct from that of viewing related three-dimensional works, as the arrangements here are presented solely from a bird’s-eye perspective. The shapes in the upper right and lower left are circumscribed by outlined borders that suggest the empty space of the floor around the sculptures, but the effect of these lines adds to the sense of systematic order rather than conveying a more accurate idea of how the sculptures actually appear in space. The drawing thus is not a study of the aesthetic of the overall sculpture or a diagram for its construction but is instead a meditation on logical systems and constitutive parts, two of Andre’s primary concerns.

Notes

1. In 1982 he stated: “I stopped attempting to make drawings for sculpture around 1960. . . . My work has never been a three-dimensional image. My work is about matter and its property of mass and mass has no reality in two dimensions.” Carl Andre, “Mass Has No Reality in Two Dimensions” (1982), in Cuts: Texts, 1959–2004, ed. Carl Andre and James Sampson Meyer (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 138.

2. Carl Andre, in Phyllis Tuchman, “Interview with Carl Andre,” Artforum 8 (June 1970): 60.

3. Blue Lock has been destroyed. Blue Lock Trial was intended to be a model and is in the collection of Lawrence Weiner, New York. Andre also made a similar sculpture, Black Lock (1967), and painted it black in honor of his recently deceased friend Ad Reinhardt. Christine Mehring, “Carl Andre,” in Drawing Is Another Kind of Language: Recent American Drawings from a New York Private Collection, by Pamela M. Lee and Christine Mehring (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 1997), 28.

4. Chipboard was not Andre’s preferred medium, and he explained that he chose it because he had only $150 for materials for this project. He described the resulting sculptures as “miserable failures,” mostly because he was dissatisfied with the material quality of the painted chipboard. Andre, in Tuchman, “Interview,” 60.

5. Mehring, “Carl Andre,” 28.

6. Jonathan T. D. Neil, “Carl Andre, Richard Serra, the Problem of Materials, and the Picture of Matter” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2010), 223.

Bios

Carl Andre

Jennifer Padgett