Matthew Bailey on Jennifer Bartlett

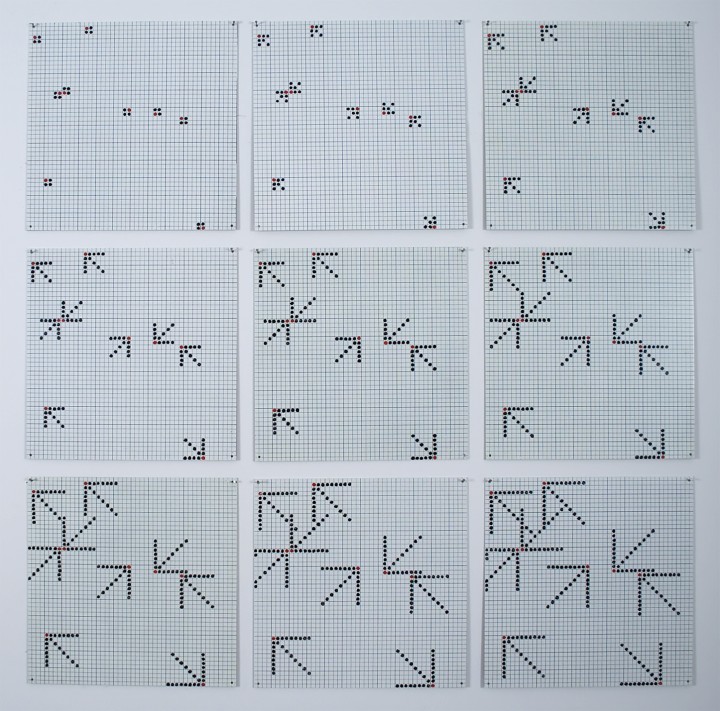

Figure 1. Jennifer Bartlett, Chicken Tracks, 1973

Enamel over silkscreen on steel plates, 38 x 38 inches (96.5 x 96.5 cm)

© 2012 Jennifer Bartlett

Jennifer Bartlett

by Matthew Bailey

Since the early 1970s, Jennifer Bartlett has used rigorous systematic procedures such as mathematical and chance operations to determine a priori the nature of her work. Together with the serialized use of the grid that characterizes her art, these strategies are a means of de-skilling, or eliminating traditional forms of manual virtuosity from her practice, in order to keep in check the arbitrary nature of artistic subjectivity. Bartlett departed from Conceptual processes, however, in her ongoing engagement with the language of representation and with the finished work of art as an object of aesthetic appeal. As Calvin Tomkins has noted, Bartlett’s work has the ring of Conceptual art but not the look: “For Bartlett, the mathematical system was not important in itself; its only function was to provide a means of getting work done. The benefits came from the physical act of applying paint, not from the system.”1

In works such as Chicken Tracks (1973; fig. 1), made by hand-painting enamel dots within silk-screened grids baked onto steel panels, Bartlett blurred the boundaries between painting and drawing as well as those between representation and abstraction. Chicken Tracks is part of her “nine-point” series, which employed a limited vocabulary of black and red dots. As a point of departure for each work, the initial placement of nine red dots on the first of nine one-foot-square steel panels was determined randomly by drawing numbers. The black dots on each subsequent panel were then arranged according to a predetermined system—in this case, the red dots served as the point of an arrow, with each line growing by one dot on each subsequent panel.2

Bartlett presumably called the finished objects Chicken Tracks because of the way the resulting abstract compositions resemble the randomly patterned steps of pecking chickens. Yet the schematic nature of her gridded dots and serialized panels seems to impose a strict order on both art and nature, reducing the meanderings of chickens to a set of predictable patterns just as repetitive operations, grids, and formulas suppress the arbitrariness of artistic subjectivity and process. If John Cage delighted in the randomness of art and nature, Bartlett delights in establishing order in both. For Bartlett, rigorous concept and aesthetic allure are not mutually exclusive but are indeed congruent. Moreover, the viewer’s perception of the artist’s systematic operations can at times be overwhelmed by the sheer pleasure of looking at her sensuous enamels and lustrous steel panels.

Notes

1. Calvin Tomkins, “Drawing and Painting,” in Jennifer Bartlett, by Marge Goldwater et al. (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center; New York: Abbeville, 1985), 17.

2. Ibid., 20.

Bios

Matthew Bailey

Jennifer Bartlett

- Calvin Tomkins, “Drawing and Painting,” in Jennifer Bartlett, by Marge Goldwater et al. (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center; New York: Abbeville, 1985), 17.

- Calvin Tomkins, “Drawing and Painting,” in Jennifer Bartlett, by Marge Goldwater et al. (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center; New York: Abbeville, 1985), 20.

Artists

- William Anastasi

- Carl Andre

- Frank Badur

- Jennifer Bartlett

- Mel Bochner

- John Cage

- Janet Cohen

- N. Dash

- Nicole Fein

- Dan Flavin

- Teo González

- Robert Grosvenor

- Eva Hesse

- Christine Hiebert

- Kristin Holder

- Nancy Holt

- Jasper Johns

- Donald Judd

- Ellsworth Kelly

- Barry Le Va

- Sol LeWitt

- Sharon Louden

- Agnes Martin

- Robert Morris

- Bruce Nauman

- Martin Noël

- Jill O’Bryan

- Larry Poons

- Erwin Redl

- Winston Roeth

- Robert Ryman

- Fred Sandback

- Karen Schiff

- Richard Serra

- Robert Smithson

- Keith Sonnier

- Allyson Strafella

- Hadi Tabatabai

- Mark Williams

@aboutdrawing

Error: Twitter did not respond. Please wait a few minutes and refresh this page.

@kemperartmuseum

Error: Twitter did not respond. Please wait a few minutes and refresh this page.

All written content © 2024 by the authors. Concept and coding © 2024 by the Fifth Floor Foundation.

Design by Yasmin Khan. Based on a parent theme by Graph Paper Press.