Janet Cohen in Conversation

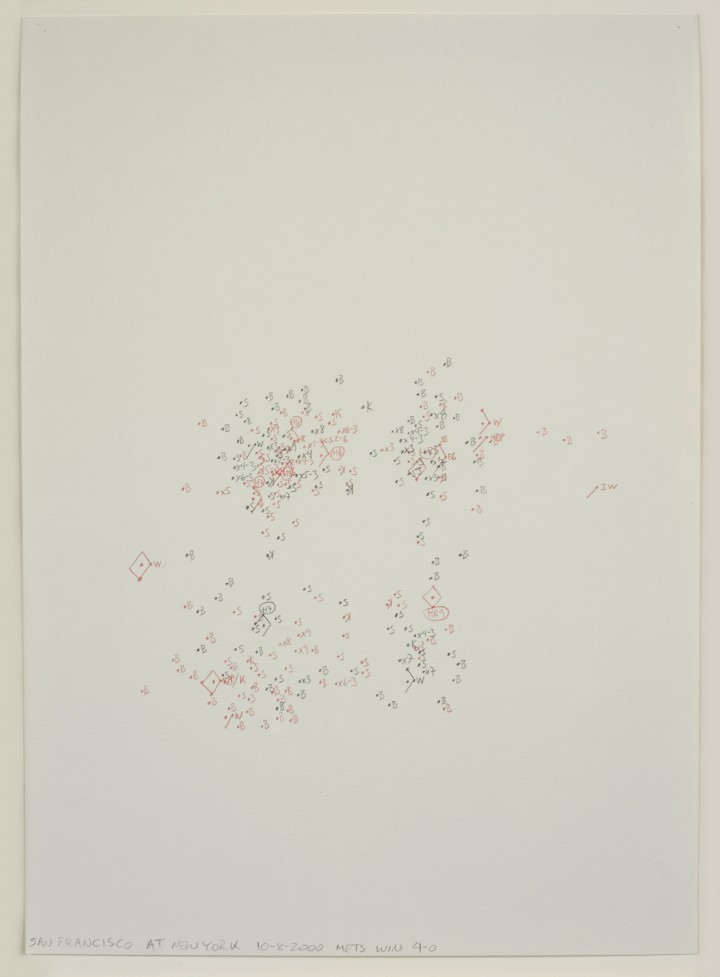

Figure 1. Janet Cohen, San Francisco at New York, 10-8-2000, Mets win 4-0, 2004

Graphite on paper, 9 1/4 x 13 inches (23.5 x 33 cm)

© 2004 Janet Cohen

Janet Cohen

In Conversation with Rachel Nackman & Michael Randazzo

April 2012, New York

Rachel Nackman: Can you tell us how you became acquainted with baseball and started making these drawings?

Janet Cohen: I grew up in Baltimore when the Baltimore Orioles were good. They went to the World Series in 1966, 1969, 1970, 1971, and 1979—five times by the time I was nineteen years old. But I wasn’t actually that into baseball as a kid. I had some baseball cards, in the typical way that most kids had baseball cards back then. I went to college in Philadelphia and was aware that the Phillies were really good at the time, but I had no great interest in watching the games. I was always a casual baseball fan.

I didn’t start making these drawings until after I graduated from Yale (the School of Art), where I studied painting and printmaking. One night I was doodling in front of the TV while watching a baseball game, just making marks on the page. I kept that drawing in my notebook for a year or so, and I realized, “I can probably do something with this.” And then, “What do I do with this?” That led to the past twenty-something years of work.

Initially I was trying to document the time of the game, although, as it happens, I ended up documenting the space where things happen. Over the years I’ve focused on both explicitly documenting the time of the game (marking off time in seconds) as well as working at making the drawings more self-contained, by which I mean that all the information you need to understand the drawing is within the drawing, not located elsewhere.

In more recent drawings, which have evolved significantly since 2000, I have been watching games and trying to find the pivot point, where the lead irrevocably went from one team to the other. That is the moment I’m trying to capture.

RN: A moment of high tension?

JC: Well, not high tension—just the moment when one team took the lead, and that was it for the rest of the game. The point at which, in an odd way, the rest of the game was sort of irrelevant. And Michael, I’m still trying to figure out how to draw game 6 from the 1986 Mets season . . .

Michael Randazzo: Right. That moment.

RN: What happened in game 6?

JC: The Mets were one strike away from losing the entire World Series to the Red Sox, and the Red Sox totally fell apart. It was a series of exceedingly fortunate events for the Mets.

The drawing included in this show is an old drawing. This is from when the Mets were good, during the last season they went to the World Series. It was in the playoffs against the San Francisco Giants, October 8, 2000. This was a great game for the Mets.

MR: This was a game that had minimal action; it was a one-hitter pitched by Bobby Jones.

JC: That’s probably why I chose to draw it. There had been no no-hitters thrown in the history of the Mets. It’s one of those statistical oddities, part of the curse of the Mets. A one-hitter is probably as close as the Mets will ever get to a no-hitter.1 This was a pretty good game.

MR: It was a good game from the action side, but what about from the drawing side?

JC: I would say that it’s not bad from the drawing side. I was surprised to see that in this drawing I was marking the pitches only as balls or strikes, adding no sequences or connections. Over time I’ve drifted toward trying to break things down into smaller periods of time, as a way to make things more legible.

RN: Can you tell us how you developed your system of notation?

JC: It started as a jumble of numbers, counting up from one until the final pitch of the game. I draw the home team’s pitches in black pencil and the away team’s pitches in red pencil. For the very first one, I was just watching a Sunday night game and drawing—this first pitch goes here; this second pitch goes there.

RN: Can you explain pitch location?

JC: Pitch location is pretty simple. It’s a matter of where the pitch crosses the plate in the plane of the strike zone. This is the conventional system that you’ve seen throughout the drawings.

RN: So the drawing documents you watching the game? Do you make these drawings while you’re at the game?

JC: It would be almost impossible to do these at the game. The drawing is premised on what used to be the conventional way of showing games on the TV: the camera is at about center field, and you almost see what the pitcher sees. (Since the TV camera can’t be directly behind the pitcher, it is slightly off from 180 degrees away from the pitcher.)

MR: Which, I’ll add, is 95 percent of what people see of a game on TV.

RN: Do these drawings take a bird’s-eye view of the strike zone?

JC: No, this is the straight-on elevation, as if seen from the center field camera. That is one thing that has stayed consistent throughout.

RN: When you’ve made adjustments to your system, what have your goals been in making those changes?

JC: Recently I’ve been concerned mostly with legibility. Over time my decision making has also become a matter of figuring out how much of the notation of the scoreboard I want to show. I see my current series of drawings as doing a pretty effective job of telling what happens in a game.

RN: When you’re thinking about telling that story, are you also thinking about the way the final result will look?

JC: Yes and no. I make plenty of decisions prior to starting a drawing (or a series of drawings) about paper size, drawing tools, and a marking system. However, once I begin the drawing, I don’t change the rules—I don’t make aesthetic decisions once the game starts. You should be able to look at the drawing without my being there, and say, “Okay, this is what’s going on.” I don’t know if there’s a polite way to put it, but I don’t think you should have to read something akin to a small novel to find out what’s there in front of you. The drawing that you have in front of you should be sufficient, combined with its title.

If you were Michael, who knows baseball, you could read the drawing and know what’s going on. But at least half the people who look at these drawings look at them in a more formalist way: “Well, why are those numbers and symbols arrayed in that setup?”

From what I’ve experienced, people who don’t know anything about baseball don’t really seem to have a problem with the drawings. It doesn’t seem to be an impossible bar to understanding.

MR: But effort on the part of the viewer will bring rewards?

JC: Sure. Effort will bring rewards, but you shouldn’t have to have a tour guide there to tell you what’s going on.

RN: Where do you work on these drawings?

JC: Normally I work on them either with a pad in my lap or at a small drafting table.

RN: Would that be in front of the TV, where you’re watching the game?

JC: It would be with the TV (or a computer monitor) not too far away, so that I rarely have to replay a pitch. I sort of consider it cheating to replay parts of the game.

MR: So you try to capture a pitch at the moment that you witness it. You’re in the zone of the game.

JC: Occasionally I get a bit of a brain freeze and have to replay pitches, but I try not to do that. It’s not a matter of trying to make the drawing perfectly, the way computer graphics can now capture a game.

MR: So the drawing is also about human perception?

JC: Yes. The same way a strike exists if the umpire says it’s a strike. It’s about the way one human perceives one issue and one event. Frankly, sometimes a good game produces a lousy drawing. Sometimes a lousy game produces a surprisingly good drawing. How good or fascinating the game is, to a baseball fan, has no relationship to whether it turns out a “good drawing.”

RN: Do you mean a good drawing visually?

JC: A good drawing in terms of visual pop or interest. I use a system that is generated by what the pitcher does, what the batter does, and what the runners do. It’s a bit like a Sol LeWitt system set loose.

There is really nothing intuitive about this process. It very roughly draws from LeWitt’s statement “The idea is the machine that makes the art.” His caveat, as I understand his writing, is that there are good ideas and bad ideas; all ideas aren’t equal.

In my catalogue of 162 drawings from one season, Estimating Pitch Location (1991–96), there were plenty of lousy games. The lousy games stay in with the good games. It’s not a matter of deciding that I’m going to show only the drawings I like. For example, if the plan ahead of time is to show a certain number of drawings of World Series games from a certain year, I show all the drawings, despite their greatness or their ugliness.

The drawings can be painful to complete, especially when a team that you don’t like is doing well. It’s annoying to deal with that. But you know, it’s work. The year that I documented Mets games—the season of 2007—it became really difficult at the end of the season to be drawing a Mets game.

MR: Did that influence the way that you reacted to the work?

JC: No, I just kept doing it, just plugged away. It kept getting worse and worse as September wore on, especially the last couple games. The Mets totally fell apart at the end.

MR: It was an epic collapse.

JC: An epic collapse, in epic proportions.

MR: Who taught you baseball scoring?

JC: I don’t know. I probably picked it up from a program at a game—nothing fancy, and there’s no real right or wrong to it.

MR: The idea of scoring the game is as old as the game itself. It’s a pretty well known system.

JC: Right. If the scorecard has been kept properly, somebody who’s reading the scorecard should be able to have good picture in his or her head of what happened during the game. I guess the point of keeping a scorecard is to have it for posterity.

MR: It’s a moment frozen in time.

JC: It’s a way of documenting events. Scorecards probably predate games being broadcast on the radio or television. (See Roger Angell’s short essay “Box Scores,” from his first collection of baseball writings, The Summer Game [1972], for a lyrical discussion of, among other things, box scores and balance sheets and the mathematics involved in baseball. For what it’s worth, any baseball fan should read everything Angell has written on baseball.)

RN: Do you want people to recognize the scorecard as a genesis for what you’re doing with the drawings?

JC: I never thought about it like that. I don’t necessarily want somebody to have a Proustian moment: “Oh yes, I remember that I kept score back when I was ten.” That’s not the goal of the drawing.

The goal is to try to document a mundane activity. These drawings really come from my need to do something other than random mark making generated by no system. It’s a nice coincidence that I get to watch something that I like to watch when doing my work. But in answer to Michael’s question, it’s not really about fandom. I’m constantly in search of other prosaic activities to document. I’ve been thinking about documenting the search for a parking spot; I’ve made some vague attempts at it, but I have yet to find a way to do that and do it safely . . .

Notes

1. On June 1, 2012, Johann Santana pitched a no-hitter for the Mets—the first and only no-hitter in the fifty-year history of the team.

Bios

Janet Cohen

Rachel Nackman

Michael Randazzo

In addition to his academic pursuits, Randazzo also helps organize conferences and special projects, including BLUR_O2, Power at Play in Digital Art and Culture with Creative Time, The Future of War with the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and The Brooklyn Cup for Kids with Young Rock Soccer Academy. A sometimes commentator on the New York sports scene for The Fort Greene/Clinton Hill Local, Randazzo resides in Brooklyn with his wife and two children.