Jennifer Padgett on Eva Hesse

Figure 1. Eva Hesse, Untitled, 1963-64

Collage, gouache, watercolor, and ink on paper, 22 x 30 inches (55.9 x 76.2 cm)

© The Estate of Eva Hesse, Hauser & Wirth Zürich London

Eva Hesse

by Jennifer Padgett

Eva Hesse was attracted to the medium of drawing throughout her career, regarding it as more flexible and immediate than painting and thus better suited for developing her own artistic approach. As an artist working in a Postminimal or antiformalist mode, she was interested in nontraditional materials, references to the body, and a rejection of the formal conventions associated with high modernist artistic practice. Hesse’s works in latex, cheesecloth, resin, and other unusual materials challenged the established standards of sculptural form; these objects connect to her drawing in their mutual pursuit of new forms that could be simultaneously ordered and chaotic, rational and irrational. In her diary she advocated the process of drawing as a means of exploring nascent concepts, writing: “If drawing gives some pleasure—some satisfaction—do it. Go ahead. It also might lead to a way other than painting, or at least painting in oil. First feel sure of an idea, then the execution will be easier.”1 This self-motivational statement expresses both permission and support, positioning drawing as an outlet for working through ideas and as a means of finding alternative methods in artistic practice. For Hesse, drawing provided ease of execution and less material resistance than working in painting or sculpture, allowing her greater freedom for creative development.

In her drawings Hesse pursued a variety of serial techniques, employing repetition as a formal and conceptual strategy, as many Minimal and Conceptual artists did during the 1960s. Her untitled drawing of 1963–64 (fig. 1) features a complex arrangement of repeating shapes. This repetition serves to emphasize the idea of accumulation, as basic shapes are reduced and repeated to allow a consideration of the relationships between them.2 Unlike the rational and impersonal serial strategies of some Minimal artists, however, Hesse’s use of accumulation and repetition takes on a more introspective, even obsessive quality.

The composition can be divided loosely into three main segments. The section on the left comprises several vertical strips of shapes such as cubes and circles stacked one atop the other. Some of the strips are relatively uniform, such as the stretch of orange rectangles near the left edge, while others are more varied. The roughly rectangular arrangement in the center is distinguished by areas of black and two arrows that appear to point toward the top edge of the sheet. On the right, a large swath of yellow, hazily outlined with gray and containing geometric shapes such as an X and a circle set into boxlike forms, dominates the grouping, with two rows of gray rectangles lined up underneath the larger shape.

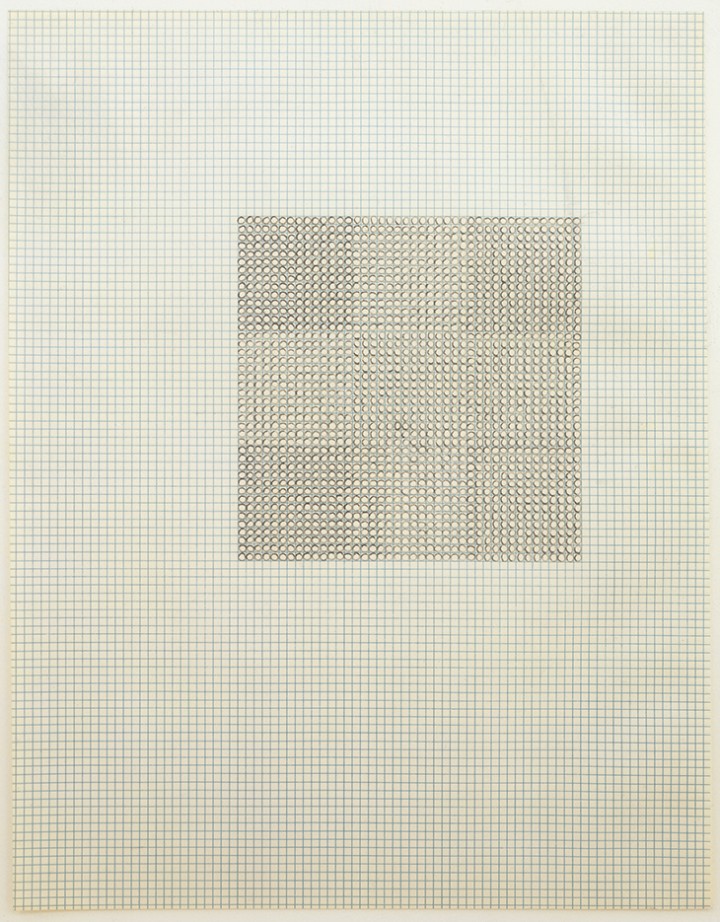

Figure 2. Eva Hesse, Untitled, 1967

Ink on graph paper, 11 x 8 1/2 inches (27.9 x 21.6 cm)

© The Estate of Eva Hesse, Hauser & Wirth Zürich London

The image imparts a chaotic sense of space and an energetic quality, as the accumulations of recurring forms build upon one another and interrelate in a play of abstract shapes. This feeling of energy is emphasized by the lively contrast of colors and the dynamic tilt of the grouped vertical forms, which add a frenetic quality to the work as they veer toward the upper left corner of the sheet. Hesse completed several similar drawings, and together they illustrate her interest in repetition—both of forms and of working methods. She believed that “repetition does enlarge or increase or exaggerate an idea or purpose in a statement” and that the statement being developed could express an interior condition or feeling.3 The repeated forms in the untitled drawing suggest the possibility of an ordered system, but because they never quite cohere or fall into a rational arrangement, they seem also to express a sense of absurdity or confusion.

Hesse’s continued interest in repetition is made manifest in her drawing of 1967 (fig. 2), one of a series of related grid drawings. On blue graph paper, she drew a square composed of black ink circles, each bounded by the borders of a single square of the graph. She varied the pressure of the pen to create variations in tone, and a cross seems to appear from the pattern of lighter circles within the larger square. The resulting work is a combination of ready-made, predetermined elements—the graph paper and its individual units—and the work of the hand, the imprecise circle marks of the pen. The grid seems to impose a certain logic, but the slight variations between the circles and the seemingly arbitrary location of the square on the sheet (slightly off-center) indicate resistance to a strictly deterministic system. Hesse used the grid, a strategy that had become a mainstay of Minimal practice by the 1960s, yet subverted it to serve her own purposes.4 She reasserted the hand of the artist and, with it, variation and unpredictability.

Notes

1. Eva Hesse, quoted in Lucy R. Lippard, Eva Hesse (New York: New York University Press, 1976), 32.

2. On Hesse and the use of repetition as a “way to engage looking,” see Briony Fer, The Infinite Line: Re-Making Art after Modernism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 8, 60.

3. Lippard, Eva Hesse, 5.

4. Elisabeth Sussman, ed., Eva Hesse (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2002), 198.

Bios

Eva Hesse

Jennifer Padgett