Elissa Weichbrodt on Fred Sandback

Fred Sandback

by Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt

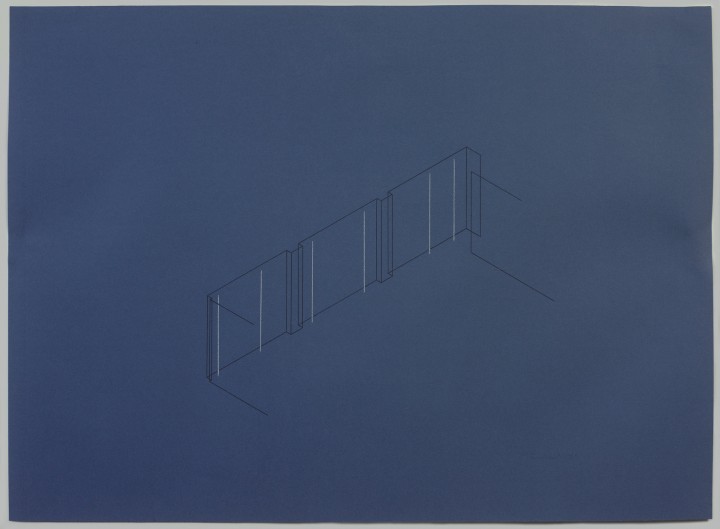

Drawn on deep blue Ingres paper, Fred Sandback’s untitled plan for an installation at the Marian Goodman Gallery (1985; fig. 1) evokes something akin to an architectural blueprint. Precise and spare, an axonometric pencil drawing of three walls of the gallery floats in the middle of the blue field. One wall, placed on a diagonal to denote recession into space, is rendered fully, while the two perpendicular walls are just barely suggested. Two narrow attached piers punctuate the main wall, dividing the space into three relatively equal sections. Six vertical white pencil lines, grouped in pairs but irregularly spaced, create another set of intervals. Although the graphite drawing clearly depicts an interior space in keeping with certain Western conventions, the demarcated walls are accorded no substance. Instead the dark lines pass through each other, disrupting a complete illusion. If, as the title suggests, we understand the space depicted to be the Marian Goodman Gallery, then the white lines represent Sandback’s proposed construction: lengths of white yarn stretched taut and run from floor to ceiling.

While the Minimal sculptures of his mentor Donald Judd emphatically occupied space, thus asserting their facticity, Sandback’s sculptural work abandoned closed volumes altogether. He considered his first sculpture to be a piece made in 1967, the outline of a rectangular solid made of string and wire placed on the floor.1 From this point on, he would continue to pursue his desire to have what he described as “the volume of sculpture without the opaque mass,” using string, elastic cord, and eventually acrylic yarn to delineate virtual spaces.2 Sandback did not create new environments with his yarn works. Instead, he thought of his sculptures, the existing gallery space, and viewers all coexisting and able to occupy essentially the same space.3

Although he insisted that his works were “still sculpture,” Sandback also described them as “drawing[s] that [are] habitable.”4 Something of this overlap can be seen in the preparatory drawing for the Goodman Gallery installation. The two-dimensional drawing usefully suggests something of the phenomenological experience of Sandback’s three-dimensional work, its crisscrossing black lines creating a sense of volume without mass, a representation of an architectural space without an interior or exterior. A similar disorientation might occur when experiencing one of his sculptures. We understand the yarn outline as a volume in space, but then, with just a blink of the eye or a slight repositioning of one’s body, the line disappears, its fuzzy edges momentarily absorbed into the surrounding space.

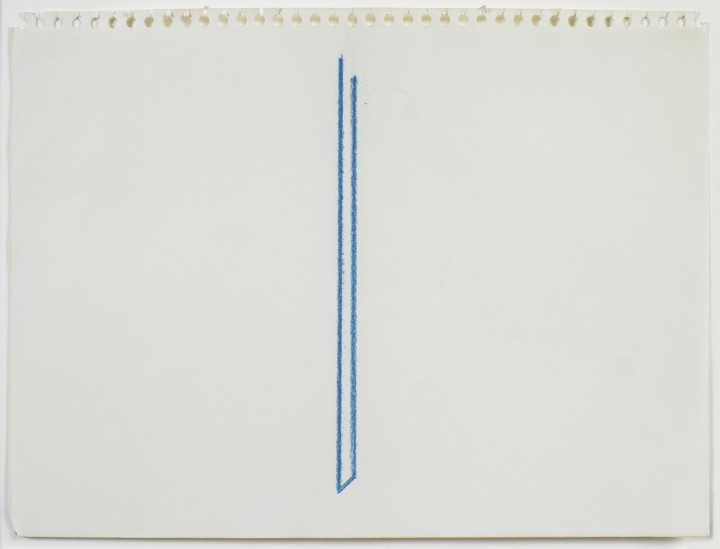

Figure 2. Fred Sandback, Untitled, c. 1975

Pastel on paper, 9 x 11 15/16 inches (22.9 x 30.3 cm)

© 2012 Fred Sandback Archive

Indeed, Sandback’s drawings even suggest the material quality of the acrylic yarn that he used to create his sculptures. An untitled drawing from about 1975 (fig. 2), rendered casually in blue pastel on a sheet of notebook paper, consists of two long, vertical lines, less than half an inch apart and joined at the bottom by a diagonal line that gives the barest suggestion of linear perspective. Unlike the crisp pencil markings of Sandback’s more architectural drawing for the Goodman Gallery, these bright blue marks have a thick, sumptuous quality. Excess specks of pigment, generated by dragging the pastel stick down the sheet of paper, soften the edges, referencing the literal softness of the yarn that they represent. The lines operate less as contours of a shape and more as marks unto themselves. Similarly, in Sandback’s sculptures, the fraying yarn calls attention to itself as a fiber while still delineating an imagined volume in space.

These works on paper operate as far more than mere flattened facsimiles of Sandback’s yarn sculptures. His drawing and sculptural practices informed each other, allowing for an exploration of the myriad possibilities of line as a formal element. Both on paper and in three dimensions, Sandback offered viewers a kind of impossible space that emerges—if only fleetingly—from a few spare lines.

Notes

1. Fred Sandback, “Remarks on My Sculpture, 1966–86,” Fred Sandback Archive, http://fredsandbackarchive.org/atxt_1986remarks.html.

2. Ibid.

3. Fred Sandback, 1975 Notes, Fred Sandback Archive, http://fredsandbackarchive.org/atxt_1975.html.

4. Fred Sandback, 1998 Notes, Fred Sandback Archive, http://fredsandbackarchive.org/atxt_1999stat.html.

Bios

Fred Sandback

Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt

Elissa Weichbrodt on Robert Grosvenor

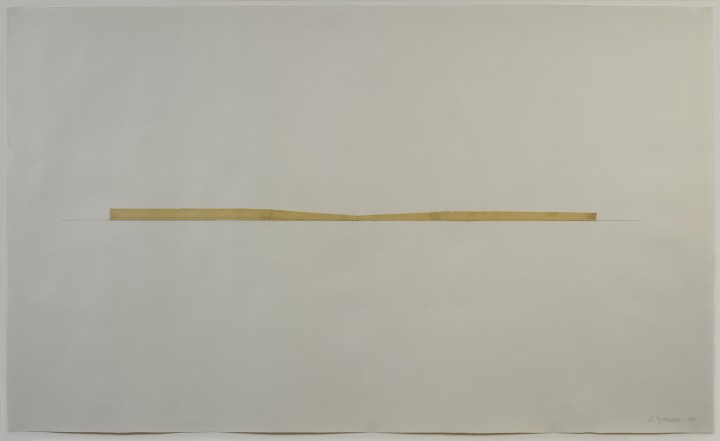

Figure 1. Robert Grosvenor, Untitled, 1974

Masking tape and graphite on paper, 29 1/2 x 49 1/4 inches (74.9 x 125.1 cm)

© 2012 Robert Grosvenor.

Robert Grosvenor

by Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt

A crisp horizontal line, drawn in pencil, floats precisely in the middle of an expanse of creamy paper. Laid parallel to and just barely touching the graphite line is a long length of yellowed masking tape that dips slightly in the middle. Spare but not clinical, the drawing evinces a sense of fragile balance. Although the tape appears to be a single strip, it actually consists of four smaller pieces; the translucence of the tape allows us to see the delicate tears where the bits overlap, creating a kind of rhythm. The subtle excavation of the central section of tape offers a moment of visual pause, which is in turn counterweighted by the darkening of the pencil line toward the ends of the tape.

This untitled drawing by Robert Grosvenor (fig. 1) is related to a series of projected sculptures consisting of timber beams placed on gallery floors or set into the earth.1 The artist often used drawing as a means of working out the structural principles of his proposed outdoor sculptures. Grosvenor described his creation of such large-scale projects as a calculated process: he would first make a central cut in a large wooden pole, excavate dirt from below the cut, and then carefully apply pressure to the center of the beam using heavy construction equipment, causing its middle section to break and sink slightly into the ground, out of view.2 In the drawing, the pencil mark designates the earth, and the sloping masking tape represents the broken beam being pushed below the ground line.

Figure 2. Robert Grosvenor, Untitled, 1973

Wood, 20 3/4 x 5/8 inches (52.7 x 1.6 cm)

© 2012 Robert Grosvenor.

This kind of large-scale sculpture was typical of Grosvenor’s practice in the early 1970s, when he abandoned monumental, gravity-defying geometric forms for timbers and wooden poles that emphasize gravitational effects. Another piece by Grosvenor in this exhibition demonstrates a scaled-down version of this approach. The untitled sculptural work (fig. 2) consists of a wooden dowel just over twenty inches long and about half an inch in diameter. A web of fine cracks encircles the middle portion of the dowel, fracturing but never quite rupturing it altogether. Though they destroy the wood’s integrity, the delicate fissures also delineate its fundamental cellular structure. Grosvenor called the resulting breaks “drawings.”3 Such a designation emphasizes the linear, surface quality of the cracks across and around the wooden beams.

Together, the splintered dowel and the masking-tape drawing offer valuable insight into Grosvenor’s process. While we might be tempted to equate the breakage of the wooden poles or timbers with a kind of impulsive, expressive violence, these preliminary studies suggest instead a degree of purposeful calculation and nuance. The delicate mesh of splinters that holds together the slender wooden stick was produced through the restrained application of pressure rather than the forceful swing of a hammer. And the plotted rupture and points of compression in the drawing, expressed by the darkened pencil line and carefully torn pieces of tape, similarly reflect the thoughtfulness of Grosvenor’s approach. The artist’s preparatory drawing and sculptural maquette attest to the fact that the larger sculptures to which they relate were created through the application not of aggressive force but of continuous, unyielding pressure, with the accumulation of stress inevitably resulting in a dispersal of energy.

Notes

1. Christine Mehring, “Robert Grosvenor,” in Drawing Is Another Kind of Language: Recent American Drawings from a New York Private Collection, by Pamela M. Lee and Christine Mehring (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 1997), 58.

2. Jordana E. Moore, “Robert Grosvenor,” in Drawings of Choice from a New York Collection, ed. Josef Helfenstein and Jonathan Fineberg (Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2002), 56.

3. Robert Grosvenor, quoted in Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe, “Robert Grosvenor: Specific Clarity,” Art in America 64 (March–April 1976): 84.

Bios

Robert Grosvenor

Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt