Amanda Beresford on Dan Flavin

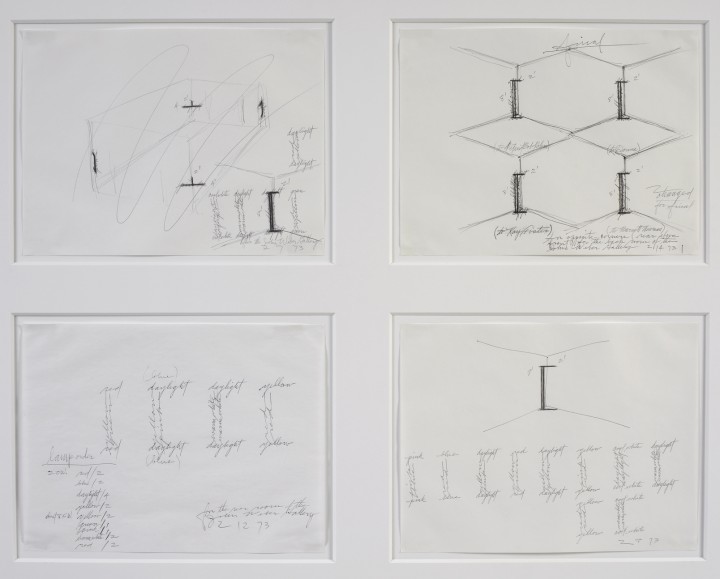

Figure 1. Dan Flavin, Four drawings for the John Weber Gallery

Feb. 7, 1973; Feb. 8, 1973; Feb. 12, 1973; Feb. 14, 1973, 1973

Ballpoint pen on typing paper, 4 sheets, each 8 1/2 x 11 inches (21.6 x 27.9 cm)

© 2012 Stephen Flavin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Dan Flavin

by Amanda Beresford

One of the leading practitioners of Minimal art, Dan Flavin was known from 1963 until his death in 1996 for his sculptures and installations made from fluorescent light fixtures and other commercially available materials. Made in 1973 for an installation at the John Weber Gallery in New York, this group of four working drawings (fig. 1) anatomizes Flavin’s method of working with fluorescent tubes to create installations in which light defines and transfigures space. The annotated drawings trace the progression of the artist’s concept from its initial trial layout to the final articulation of the installation, functioning both as records of his thought process as he elaborated and changed his design and as diagrams for the construction of the work. The drawings thus enable the viewer to follow and comprehend, in several stages, Flavin’s unique creative path.

Flavin recorded his ideas for artworks in notebooks that he carried everywhere, sketching layouts and annotating them extensively with technical details. These constituted his primary creative input into the final installations, which were ultimately executed by technicians. In contrast to his detailed and specific working drawings, the end products, constructed of store-bought materials, de-emphasized any physical intervention on the part of the artist. Flavin underlined the importance of drawing to his work in 1973, the year he made these sketches: “I have come to understand that, for me, drawing and diagramming are mainly what little it takes to keep a record of thought…. Within my reciprocating system for fluorescent light such continuous retention is constantly required.”1

Unlike some of the highly finished presentation drawings in Notations (for example, those by Mel Bochner and Sol LeWitt), Flavin’s sketches are rough and spontaneous, exposing the artist’s hand and thus taking on an autographic quality. The idiosyncratic, personal nature of the sketches appears in distinct contrast to the industrial finesse of Flavin’s installations. Each drawing reveals the artist’s consciousness of time and space: all are dated, so the order of their execution can be established, and three are inscribed with a variant of “for the rear room of the John Weber Gallery.”

The three earliest drawings show various projected arrangements for the light-tube assemblages, annotated with dimensions, wattage values, potential color combinations, and locations in the corners of the room. One room layout is scrawled over, marked as rejected. In the fourth drawing, headed “final,” several corner placements are arrayed in a decorative pattern, their perspective angles forming a grid of open and closed diamonds and hexagons. This is simultaneously instructive, aesthetically pleasing, and visually deceptive; the drawing’s aesthetic qualities work against its utilitarian nature as a technical diagram. Referring to the arrangement of the light fixtures, Flavin said, “I never neglect the design.”2 Here he established a tension, also apparent in the finished artwork, between its aesthetic effect and the industrial materials and method of its construction.

Handwritten text is integral to each drawing, providing technical instructions and serving as a structural component. Flavin constructed the forms of his light-tube assemblages from the words that indicate the colors of their lamps: red, yellow, green, pink, blue, daylight, warm white, and cool white. The written words have a double signification, indicating both the color of the light to be produced and the form of the object producing the light. Flavin made language a surrogate for object, privileging the conceptual over the physical nature of the artwork in drawings that chart the concept’s evolution.

The trials, rejections, and hesitations that these drawings acknowledge emphasize process, exposing the role of contingency and choice in Flavin’s mode of creation. These rapid working sketches on common notebook or typing paper were essential to his methodology. He made his drawings as a means of thinking through and recording his installations, but for the viewer they elucidate the relationship of the artist’s working process to his finished work.

Notes

1. Dan Flavin, quoted in Isabelle Dervaux, Dan Flavin Drawing (New York: Morgan Library and Museum, 2012), 113.

2. Dan Flavin, “Some Other Comments . . . ,” Artforum 6 (December 1967): 23, quoted in Eun Young Jung, catalog entry for Jill’s Red Red and Gold of December 9, 1965, in Drawings of Choice from a New York Collection, ed. Josef Helfenstein and Jonathan Fineberg (Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2002), 44.

Bios

Amanda Beresford

Dan Flavin