Christine Hiebert in Conversation

Figure 1. Christine Hiebert, Untitled (t. 02. 3), 2002

Blue tape on paper, 13 7/8 x 16 3/4 inches (35.2 x 42.5 cm)

© 2012 Christine Hiebert

Christine Hiebert

In Conversation with Rachel Nackman

March 2012, New York

Rachel Nackman: Your drawing Untitled (t.02.3), from 2002 (fig. 1), was made with blue painter’s tape. When did you start using that material, and how did you encounter it?

Christine Hiebert: Sometimes you have to trick yourself into making new work. I started to use blue housepainter’s tape in 2000 while thinking about building a house—but I quickly lost interest in that project when I saw that I could use blue tape to make new drawings. I saw a link between my subject matter and the material, because I’ve been thinking about structure and dwelling in my work for a long time.

Every time I start a drawing, it’s really a marriage between the medium—the tool that I’m drawing with—the surface, and me. It’s very important for me to let the medium reveal itself so that I can learn from it: each medium has a different nature. The tape gave the drawings a different look: hard-edged, industrial, temporary, and very bold. But it also had the potential to be delicate. Given the range and flexibility of tape, I could really manipulate the line in order to continue my exploration of structure and space.

RN: Was there a process of learning how to work with it practically, to make the line do what you wanted it to do?

CH: I was familiar with tape from my years studying graphic design. Before the computer, we had a way of making smooth, curved lines by bending very thin strips cut from tape . . . so I felt comfortable working with it. But I had never thought of using it in a drawing until that moment.

RN: On what scale did you start working with it?

CH: I started to use it on the wall, so it began acting on the real, physical space of a room right away. The wall felt like a natural place to work with that line (housepainters use blue tape on painted walls—it belongs there). Later I started to make some small studies on paper, and those were really about figuring out how to join things. Originally I didn’t intend these studies to be pieces that stood alone. I was just trying to figure out some things about overlapping—how lines come together, how they hold each other up.

What became clear is that the tape works on paper didn’t act, for me, as sketches for larger works. Each one really was its own little event on paper.

RN: Did you notice any change in the quality of the tape line as you moved from working on the wall to working on these more contained sheets of paper?

CH: I had always worked with graphite and charcoal, and those media pick up the movements of the hand in such a sensitive way. The tape wants to do something else—so there are twisty, curvy lines or turning lines or awkward, jagged lines, but there are also a lot of straight, bold lines. That’s just the nature of tape. And any of the drawings has a greater sense of intimacy on paper than it would on the wall.

RN: Once you started working with tape on paper, did you then move back to working with tape on the wall?

CH: I wasn’t much interested in working on the wall in my studio. There are too many things going on there, and to make a wall drawing, I needed to be able to act fully on the space of the room. So in the studio I worked on pieces on paper, and whenever I had a chance, I would find some kind of public wall—a gallery or museum wall to work on. For each new project, I looked for a wall that had a different set of conditions—different shapes, dimensions, architectural considerations, light conditions—so that each drawing could respond to something new.

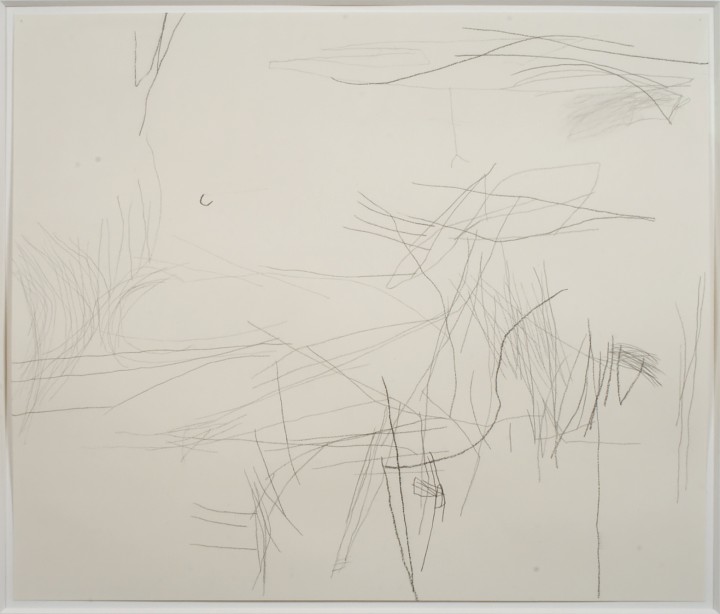

Figure 2. Christine Hiebert, Untitled, 2006

Graphite and charcoal on paper, 14 x 16 1/2 inches (35.6 x 41.9 cm)

© 2012 Christine Hiebert

RN: Before you started working with blue painter’s tape, you had been working primarily with graphite and charcoal. Your untitled drawing from 2006 (fig. 2) is made with graphite and charcoal on paper. Can you tell us how you started working with these tools?

CH: I’ve been working in charcoal since 1989. No matter what other kinds of drawing media I’ve used since then, I have always been working with charcoal at the same time.

At one time I wanted to be a painter, so I tried working in oils for a while. One day I decided I wanted to work large and didn’t have large canvas, so I set out to make a very large painting on paper. This was the first large-scale surface I had attempted, and after some frustration I picked up a piece of charcoal in order to move more quickly across the paper. I never went back to paint. I had been working small for a long time, and I felt a need to work larger. I saw that I could activate a large field more quickly with drawing because drawing is more direct. And it was easier for me to orient myself in this larger field by making a charcoal mark than a painted line.

I tried to continue some of the smaller paintings for a while, but I found that I could not be as direct and spontaneous with oil paint. I’d pick up the brush, wanting to do something in particular, and I’d put the brush to the paper—but then the brush would give. In the moment that the brush would give, I would lose my connection. I would lose the impulse. I found that very frustrating. A rigid tool, like a stick of charcoal, was much more gratifying. It responded immediately, and I could run with it.

RN: So your choosing graphite and charcoal was in part about retaining an element of control?

CH: It didn’t feel like control; it felt like directness. I know that one can say there’s sense of control in drawing that’s different from what happens in painting, but I also felt like the drawing tool could be itself a little bit more. With a paintbrush I felt like I was always the one making it happen.

RN: So you took out the middleman?

CH: I took out the middleman, exactly. [Laughter.]

RN: How has the gesture itself changed from earlier in your work to the late 2000s?

CH: Early on, I didn’t see the lines as single lines. They were put together in such a way that they merged with other lines; they sometimes even made shapes.

The lines have become more and more isolated. They may be layered, especially in more recent years, but I still think of them as individuals.

RN: Rather than as components that make a whole?

CH: Yes. They have to act in both ways—as individuals and as components—but I am especially interested in lines as individuals. The lines became more varied over time. My introducing these other media—like the tape and the ink roller—and combining them allow for a lot more variation among the lines in a single drawing.

RN: Does that possibility affect your process of placing the lines on the page?

CH: At times that process can be very self-conscious, but that’s the problem I’ve set up for myself. I’d rather not be so self-conscious. I’d rather run with the kind of fluidness that these lines suggest. I feel like the drawing challenges me to do that, and often I have trouble meeting the challenge. I sit back and wait, and then I hang onto and protect these lines. I’m not always ready to let them go. That’s a life challenge, and that’s why I think drawing is so engaging for me.

RN: Your process seems so editorial—in the way that you approach the empty space of the page or the space of the wall, it seems that there’s a lot of placing and stepping back, thinking, and re-placing. Are you saying that this type of process is one part of your search for something more fluid or immediate?

CH: Well, you can’t be completely free. [Laughter.] I think what I’m trying to do in my work is to balance these two states of being. Have a sense of freedom but also develop some kind of conscious understanding. That editing is more conscious—it’s more controlled.

RN: Can you walk us through what the application of line might feel like to you?

CH: Well, I never know what’s going to happen. I think I’m starting to do one thing, and then I go somewhere else. Blue painter’s tape turned out to be a very good drawing material for me because it’s removable—it’s very easy to take it away or to change it once you’ve put it down.

I might have a couple different widths of tape already cut; that’s my palette. Then I’ll start to place pieces of tape on paper and pick them up, place them down and turn them, pick them up and place them down, move them and turn the paper, decide I need different width lines, go right back to the cutting board, cut new widths . . .

This might take days, or it might take a couple of hours. Usually I don’t finish a piece in one session. The drawing needs some time when I’m out of the room.

RN: Is it the same for the drawings with charcoal?

CH: It’s the same process. The first marks I make on the paper tell me where to go. Over time, what gets revealed is a certain general sense of space that I might have started out with—although I can lose that.

RN: You’ve said that you don’t think that any of the lines are architectural per se, but that they come from an architectural source or structure, from building . . .

CH: Well, there is no architectural “source.” The putting-together is what relates to architecture. Each line reflects the nature of the tool, and they all reflect my nature. They’re organized: they’re joined, they interact with each other, they claim space, they provide passage. In this way the drawings are “built.”

I’m very aware of how the lines move. Any hand-drawn line has direction. It starts at one point, and it ends somewhere else. It moves at different speeds; it moves in different ways: it lurches, it becomes upright, it falls over, it wafts through the air. I’m interested in how all these different elements can live together—this variety of lines with different character. They are my materials at hand. Now how can they work together?

When I talk about architecture, I mean the human activity of creating structures to provide residence. In the past I have sometimes thought about the drawing as a metaphor for human habitation, but even that feels too literal for what I’m doing. I am really looking for each drawing to provide a place for the viewer—a way in, a way to interact with the lines and to stay with them. “Residence” seems like a condition that is important in seeing, in knowing.

Bios

Christine Hiebert

Rachel Nackman