Jennifer Padgett on Carl Andre

Figure 1. Carl Andre, Subfield, 1966

Ceramic magnets, 84 units, rectangle 6 x 14, 1/2 x 18 x 13 5/8 inches (1.3 x 45.7 x 34.6 cm)

Art © Carl Andre/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Carl Andre

by Jennifer Padgett

Carl Andre’s work in drawing is intrinsically linked to his sculptural objects, although the artist has resisted the notion that preparatory drawing is important as a conceptual exercise in the creation of three-dimensional objects.1 As one of the leading figures of Minimal art, Andre has continually emphasized the material object and its presence in space over any kind of concept or “idea” generated by the artist and meant to be conveyed through the work. In his floor pieces and other sculptural works, he has focused on viewers’ experiences and their movements in relation to the work. He has described his approach as materialist as opposed to conceptual, claiming, “I am certainly no kind of conceptual artist because the physical existence of my work cannot be separated from the idea of it.”2 Andre believes that a work of art should be derived from the specific properties of the materials employed and that this is best achieved through direct physical interaction rather than by plotting out preconceived ideas through drawing.

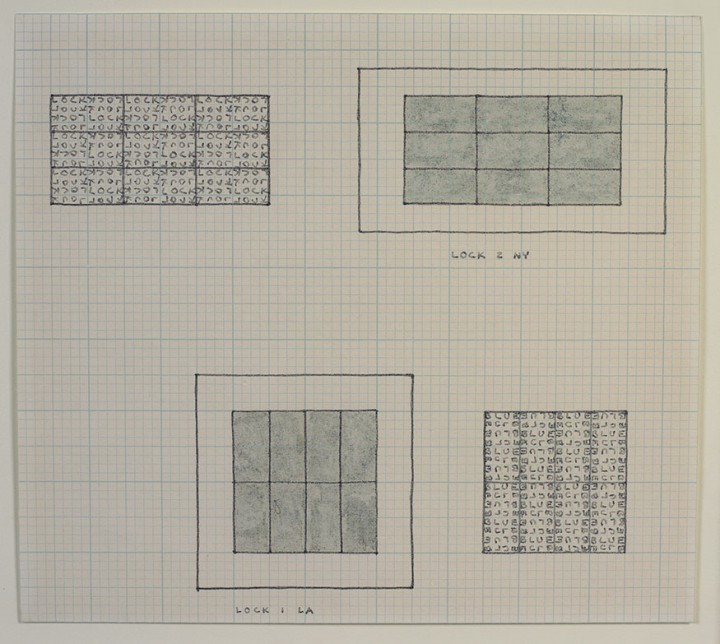

Figure 2. Carl Andre, Blue Lock, 1966

Colored ink and felt-tip pen on graph paper, 8 3/4 x 9 3/4 inches (22.2 x 24.8 cm)

Gift of Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Art © Carl Andre/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

The drawing Blue Lock (1966; fig. 2) is therefore connected to Andre’s sculptural work but also reflects a calculated employment of the specific properties of drawing as a medium. The four rectangular configurations depicted here in colored ink and felt-tip pen on graph paper relate to the sculptures Blue Lock Trial (1966) and Blue Lock (1967).3 Andre’s Lock sculptures were constructed of chipboard, a material selected out of economic necessity and painted blue to suggest a steel surface.4 Each of the rectangular arrangements in the upper half of the drawing comprises a series of smaller rectangles, arranged three across by three down and aligned with the overall grid of the paper although slightly offset from the preprinted pattern. These drawn rectangles directly reference Blue Lock Trial, as indicated by the notation below: “LOCK 2 NY.” The two configurations in the lower half of the sheet are composed of similar rectangular pieces, turned on end and arranged in a pattern of four across by two down, resulting in an overall square. The notation for this pair, “LOCK 1 LA,” links them to Blue Lock, which was commissioned for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s exhibition American Sculpture of the Sixties (1967).

Each individual square making up the rectangle in the upper left contains one of the four letters that spell lock in the square in the lower right corner of the sheet, the letters that spell the word blue are arranged in a similar fashion. These words are oriented in various directions, resulting in a puzzle-like effect. By implying a number of positions from which to read the words, the lettering suggests a turning of the sheet that echoes the movement of a viewer around the sculptural object in space.5 The interlocking word patterns also suggest a kind of interior logic organizing the pieces within the larger shapes. Andre was deeply interested in ordering systems, and in works such as Subfield (1966; fig. 1), he explored how such systems could be intrinsic to the materials used.6 This sculpture consists of eighty-four ceramic magnets, arranged in a rectangular shape and held together by magnetic force upon the proper alignment of their north and south poles. The structure and arrangement of the overall work are thus determined by qualities inherent in the material itself, which suits Andre’s materialist approach. In the drawing Blue Lock, the graph paper supplies the predetermined logic on which the artist builds to suggest a deeper rationale underlying the organization of subparts.

The experience that the drawing offers is distinct from that of viewing related three-dimensional works, as the arrangements here are presented solely from a bird’s-eye perspective. The shapes in the upper right and lower left are circumscribed by outlined borders that suggest the empty space of the floor around the sculptures, but the effect of these lines adds to the sense of systematic order rather than conveying a more accurate idea of how the sculptures actually appear in space. The drawing thus is not a study of the aesthetic of the overall sculpture or a diagram for its construction but is instead a meditation on logical systems and constitutive parts, two of Andre’s primary concerns.

Notes

1. In 1982 he stated: “I stopped attempting to make drawings for sculpture around 1960. . . . My work has never been a three-dimensional image. My work is about matter and its property of mass and mass has no reality in two dimensions.” Carl Andre, “Mass Has No Reality in Two Dimensions” (1982), in Cuts: Texts, 1959–2004, ed. Carl Andre and James Sampson Meyer (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 138.

2. Carl Andre, in Phyllis Tuchman, “Interview with Carl Andre,” Artforum 8 (June 1970): 60.

3. Blue Lock has been destroyed. Blue Lock Trial was intended to be a model and is in the collection of Lawrence Weiner, New York. Andre also made a similar sculpture, Black Lock (1967), and painted it black in honor of his recently deceased friend Ad Reinhardt. Christine Mehring, “Carl Andre,” in Drawing Is Another Kind of Language: Recent American Drawings from a New York Private Collection, by Pamela M. Lee and Christine Mehring (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 1997), 28.

4. Chipboard was not Andre’s preferred medium, and he explained that he chose it because he had only $150 for materials for this project. He described the resulting sculptures as “miserable failures,” mostly because he was dissatisfied with the material quality of the painted chipboard. Andre, in Tuchman, “Interview,” 60.

5. Mehring, “Carl Andre,” 28.

6. Jonathan T. D. Neil, “Carl Andre, Richard Serra, the Problem of Materials, and the Picture of Matter” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2010), 223.

Bios

Carl Andre

Jennifer Padgett