Amanda Beresford on Keith Sonnier

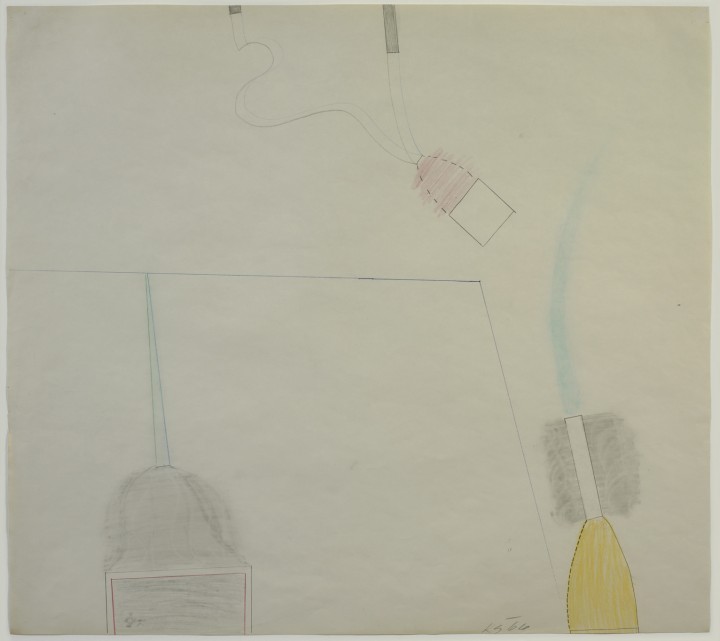

Figure 1. Keith Sonnier, Early Rutgers Drawing, 1966

Ink, graphite, and colored pencil on paper, 20 x 22 1/2 inches (50.8 x 57.2 cm)

© 2012 Keith Sonnier / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Keith Sonnier

by Amanda Beresford

Keith Sonnier’s Early Rutgers Drawing (1966; fig. 1) dates from the period when the artist was studying with Robert Morris on a graduate teaching fellowship at Rutgers University. He was part of a group of artists whose work was later labeled Postminimal. The term relates to various art practices that emerged in the mid-1960s and were characterized by an irreverent attitude that questioned not only traditional “high art” categories and materials but also cerebral Minimal orthodoxy. Sonnier—together with Richard Serra, Bruce Nauman, Eva Hesse, and other like-minded artists—worked with industrial materials such as felt, fiberglass, plastics, and in Sonnier’s case, lightbulbs and neon tubing. These artists introduced what Robert Pincus-Witten called “a new sensibility” into the art world, rejecting the Minimal credo that eschewed subject matter and emotional content by creating works that incorporated references to popular culture and invited the viewer to interact.1

By the late 1960s Sonnier had gained recognition for his playfully exuberant “drawings with light”—sculptural installations using neon tubes and other industrial materials suffused with sensuous color—but conventional drawing on paper is not so readily associated with his practice. This early example is a revealing document of his thinking during a particularly formative year.2 The sheet is a diagram for a light installation using colored lamps, but it betrays a playful subjectivity foreign to most Minimal artists’ drawings of the same period. Using colored pencils and graphite, Sonnier depicted three light fixtures of different types and colors, suspended in an undefined space: a red tulip-shaped fixture with a white collar; a yellow tulip-shaped fixture without a collar; and a gray fixture with a wide rectangular mouth, possibly a floodlight. All three are connected to what may be power cords, tubes, or something more atmospheric, such as air or beams of light. The spatial relationships among the drawing’s elements are ambiguous, however; it is not clear whether we are looking down on the installation from above or up at it from below. The red light apparently has a double tubing, and its serpentine curves inject a sensuous vivacity into the composition. The yellow lamp is positioned at the end of a shallow blue arc, and the gray fixture is either suspended by a straight blue component from an obliquely angled frame, indicated by a simple pencil line, or possibly sitting on the floor. (Sonnier began to experiment with low, floor-based assemblages around this time.)

Although this drawing dates from before Sonnier began using neon in 1967, it demonstrates an engagement with the luminosity of the colored lamps and the nature of light as it permeates space. The colored-pencil shading on the red fixture spills over its outline, suggesting the diffusion of its radiance. The yellow lamp’s blue cord lacks an outline, also suggesting a diffuse radiance, and fades away toward the upper right corner. It is connected to a white section of tubing shown against a gray shaded background; this section appears to radiate darkness, in a negative impression of the preceding effect. A subtle light surrounds the gray fixture, providing a fugitive sense of volume; a thin red line emphasizes the lamp mouth’s inner border. Reflecting on his methods of working with color, Sonnier spoke in 2006 of learning “to treat color as volume” and to exploit its psychological use. This drawing represents an early gesture in this direction.3

Sonnier’s attention to power cords and fixtures and his decision to allow them to become part of the installation rather than hiding them prefigure his readiness in later installations to expose “the mechanical underpinnings” of his works of art.4 The slightly awkward draftsmanship and the sense of rapid execution are characteristic of what Richard Kalina calls his early work’s “brashness” and “offhanded” quality.5 Sonnier was already seeking alternatives to the materials and methods of “high” modernism, a practice that he would take to extremes in his future work with neon, video, and all manner of unconventional and everyday substances, including foam rubber, latex, mirrors, and sailcloth, each “deliberately chosen to psychologically evoke certain kinds of feelings” (although he did not say what those feelings are).6

Another tendency that this drawing forecasts is the theatricality of much of Sonnier’s subsequent work. Critics have commented on the self-consciously dramatic presentation of some of his installations, the dance of the colored gases in their neon tubes, and their deliberate engagement with the spectator. The artist himself, in a recent interview, compares his work to a theater set and the act of making it to the experience of acting in a play.7 Sonnier, like Picasso, may see himself as an actor in the drama of his own art making, but in this drawing he functions more as a playwright or director, asking each of the three lamps to assert its individual character and perhaps inviting the audience to engage with his playful blueprint for experimentation in a new medium.

Notes

1. Robert Pincus-Witten, Postminimalism (New York: Out of London, 1977), 34.

2. “Drawing with Light” is the title of an article on Sonnier by Richard Kalina in Art in America 92 (April 2004): 114–19. In 1966, the year this drawing was made, Sonnier’s work was included in Lucy Lippard’s Eccentric Abstraction, a seminal exhibition for Postminimal art.

3. Keith Sonnier, in Patricia Rosoff, “Electrifying the Inert: A Conversation with Keith Sonnier,” Sculpture 25, no. 1 (2006): 57.

4. Kalina, “Drawing with Light,” 116.

5. Ibid., 116, 119.

6. Keith Sonnier, in Max Blagg, “Keith Sonnier” (interview), Interviewmagazine.com, May 2012, http://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/keith-sonnier/.

7. Ibid.

Bios

Amanda Beresford

Keith Sonnier

Amanda Beresford on Larry Poons

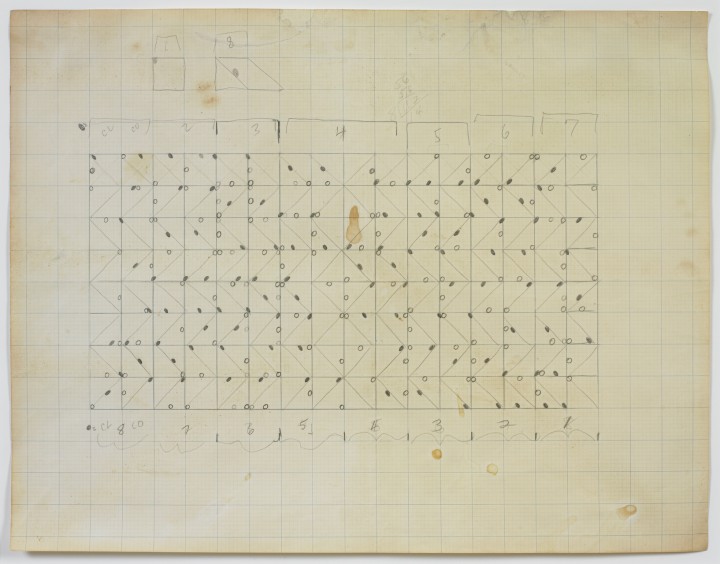

Figure 1. Larry Poons, Untitled, c. 1964

Graphite on graph paper, 17 5/8 x 22 3/8 inches (44.8 x 56.8 cm)

Art © Larry Poons/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Larry Poons

by Amanda Beresford

Larry Poons’s untitled pencil drawing of around 1964 (fig. 1) was made as a study for one of his signature dot paintings of the early 1960s. These paintings consisted of carefully calculated arrangements of dots (and later ellipses) on intensely saturated color fields, the opposing hues of object and ground generating an illusion of movement as well as a colored afterimage in the viewer’s eye. The execution of these works required intensive planning, as this drawing demonstrates.

At art school in the 1950s, Poons was convinced that he could not draw: “I tried. But I found a way—or it found me, I suppose—where if I didn’t look at the paper, and didn’t look at what my hand was doing, and just looked at what I was drawing, I could do it much better than I’d ever done before.”1 He began organizing fields of dots and ellipses on a precise mathematical grid like the one in the present drawing, calculating not only the exact position that the shapes would occupy on the painted canvas but their optical trajectory for the viewer as well. The drawing is squared on graph paper, with the field of the projected painting divided into numbered sections along its upper and lower horizontal axes. Each square is neatly bisected by a diagonal line, alternating in direction with the lines above and below it to create a zigzag pattern. These lines would not be visible in the final painting, but their pattern is indicated by solid elliptical dots. Pointing along the diagonals, the lines of dots add to the directionality of the composition and to its sense of movement. Their shapes are interspersed, seemingly at random, with open circular dots situated on the horizontal and vertical axes of the grid. When transferred to canvas, the precisely positioned dots create the effect of an alternate pattern of movement, generating an optical illusion of space through the interaction of the two shapes, ellipse and circle. The presence of faint pencil lines, as well as smudges and what may be coffee stains on the sheet, reinforces the drawing’s status as a working diagram for a finished painting.

Poons’s work is associated with both 1960s color-field painting and the emergence of Op art, a development focused on color, movement, and the psychology and physiology of perception. He stated that the much-cited afterimage that his paintings produce was at first an unintended effect of his intense palette of brash commercial colors,2 but he was quick to grasp the potential for this work to “explore and extend the range” of optical perception.3 Indeed, the visual experience of his color rhythms has elicited for some viewers an “almost kinesthetic response.”4 Poons has claimed inspiration for his abstract dot paintings from sources as diverse as astronomy—he enjoyed drawing constellations when he was young—and the “crisscrossing” movement of multitudes of pedestrians on Wall Street.5 His plotted diagram is evocative of these sources, offering a look into the artist’s thought process and his meticulous approach to art making.

Notes

1. Larry Poons, in Robert Ayers, “‘There’s No Gap between Seeing and Understanding’: Robert Ayers in Conversation with Larry Poons,” A Sky Filled with Shooting Stars (blog), February 25, 2009, http://www.askyfilledwithshootingstars.com/wordpress/?p=194.html.

2. Henry Geldzahler, “An Interview with Larry Poons, 1963,” in Making It New: Essays, Interviews, and Talks ([New York]: Turtle Point, 1994), 66.

3. James N. Wood, Six Painters (Buffalo, NY: Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, 1971), 11.

4. Ibid, 14.

5. Poons, in Geldzahler, “Interview with Larry Poons,” 67, and in Ayers, “There’s No Gap.”

Bios

Amanda Beresford

Larry Poons

Amanda Beresford on Martin Noël

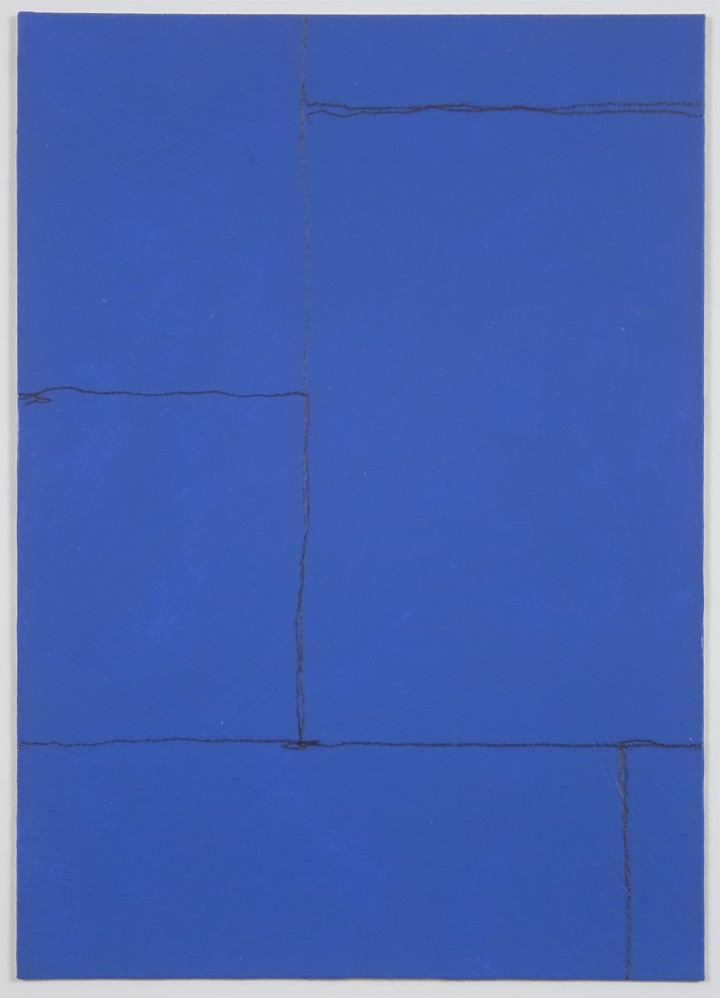

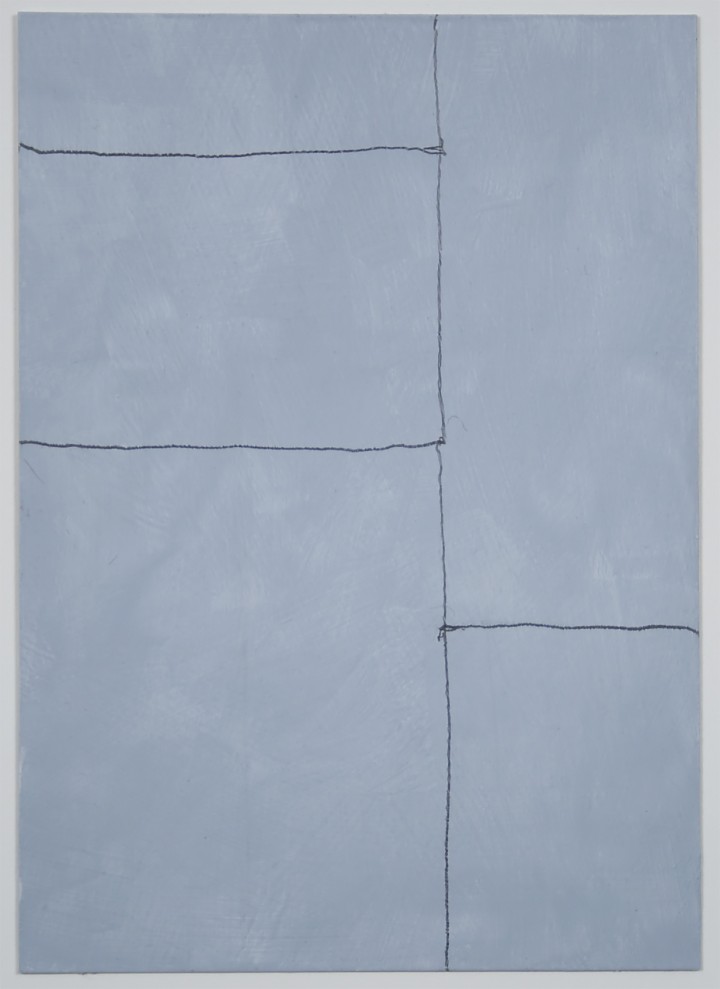

Figure 1. Martin Noël, Untitled from the Freundlich series, 2007

Acrylic and graphite on postcard, 6 x 4 1/2 inches (15.2 x 11.4 cm)

© 2012 Martin Noël. Courtesy Margarete Noël

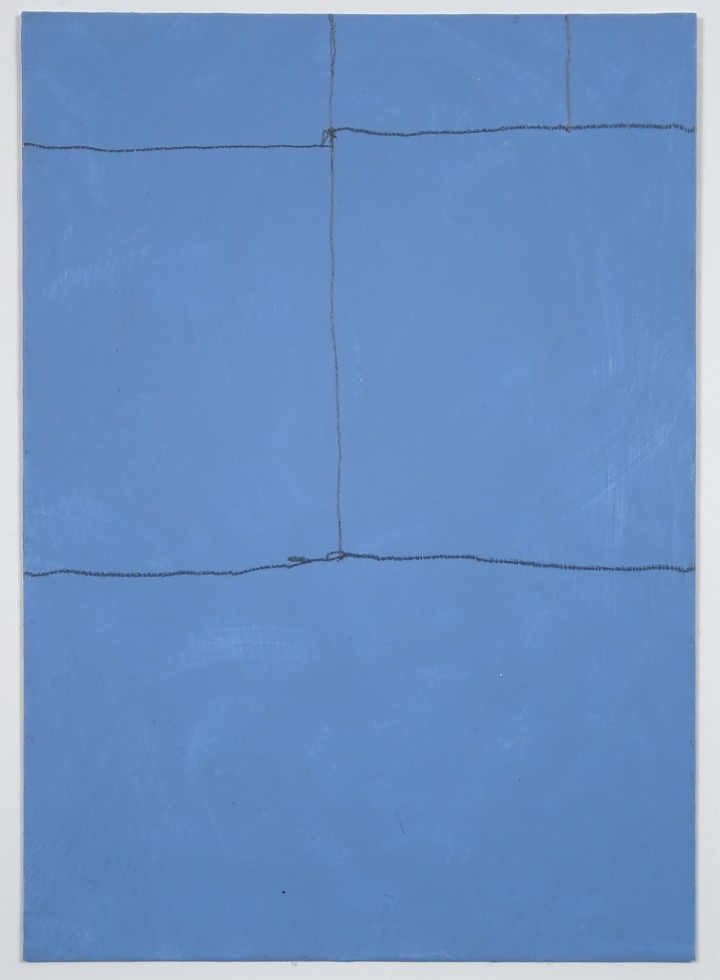

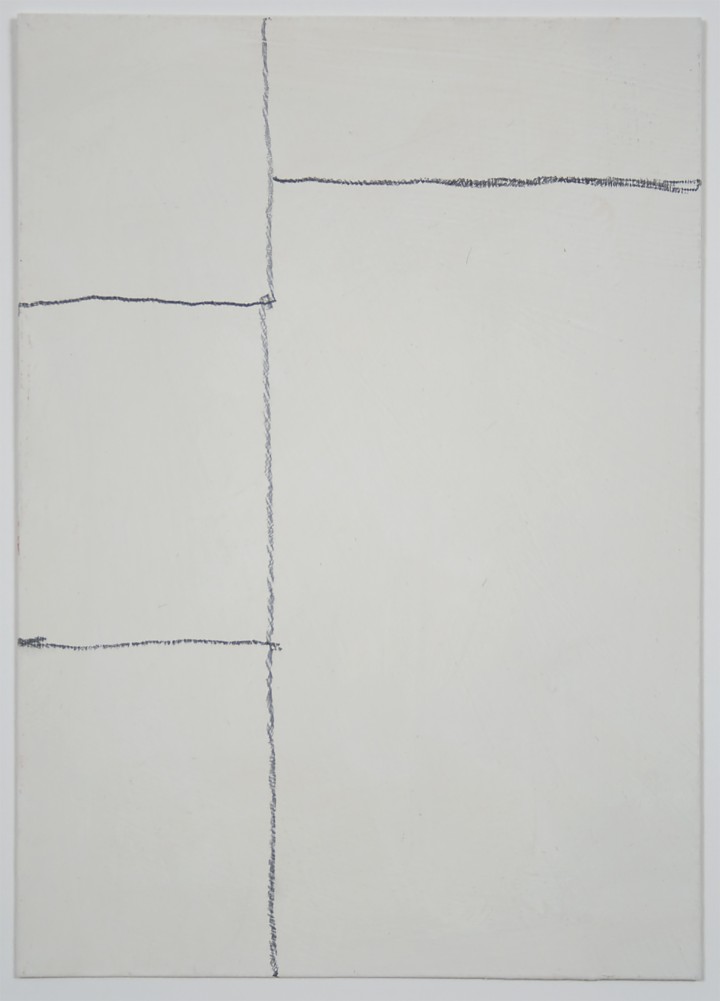

Figure 2. Martin Noël, Untitled from the Freundlich series, 2007

Acrylic and graphite on postcard, 6 x 4 1/2 inches (15.2 x 11.4 cm)

© 2012 Martin Noël. Courtesy Margarete Noël

Martin Noël

by Amanda Beresford

Born in Berlin in 1956, Martin Noël trained in Cologne, becoming one of the leading figures of the Rhineland art scene in the 1970s. He was active in Bonn as a painter, draftsman, and printmaker in woodcut until his death in 2008. Transcendence has been described as a central theme of Noël’s work.1 These four drawings from the Freundlich series (figs. 1-4), executed in the year before his death, could be interpreted as reflections on an ideal or transcendent state, but they also display parallels with the use of seriality as a strategy in art of the 1960s and 1970s: the repetition or elaboration of a few elements in a process of continual, seemingly random realignment; the sense of infinite variability that this engenders; the works’ coherence as a group; and the notion of the progressive metamorphosis of a central theme in search of its ideal form.2 Devoid of the mechanical or systematic detachment particular to Minimal and Conceptual serial imagery, Noël’s work is organic, instinctual, and informed by his private vision.

The drawings consist of four simple but mysteriously compelling compositions of horizontal and vertical lines intersecting at right angles, drawn freehand on standard-size postcards. The background colors of the postcards deepen gradually from off-white to slate blue-gray to a rich cornflower blue to an intense cobalt. The play of asymmetrical horizontals and verticals in the drawings varies subtly but markedly, each offering a different dynamic of just four lines in the first three images and of five in the fourth. The dominant vertical line shifts from the left in the first drawing to the right in the second, each with three horizontal branches extending to the outer edge of the postcard. The third drawing presents two equal horizontals that traverse the width of the card, supporting two shorter verticals, with an empty space occupying almost the entire lower half. A greater equilibrium in the length and placement of lines and in the areas that they define is achieved in the fourth drawing, giving a sense of unequal, opposing forces held in balance. The drawings’ depthless picture planes read either as lines precisely arranged on a field or as a field divided into irregular but complementary tesserae.

Figure 3. Martin Noël, Untitled from the Freundlich series, 2007

Acrylic and graphite on postcard, 6 x 4 1/2 inches (15.2 x 11.4 cm)

© 2012 Martin Noël. Courtesy Margarete Noël

Figure 4. Martin Noël, Untitled from the Freundlich series, 2007

Acrylic and graphite on postcard, 6 x 4 1/2 inches (15.2 x 11.4 cm)

© 2012 Martin Noël. Courtesy Margarete Noël

Together with the deepening chromatic intensity of the postcards, the choreography of linear configurations suggests a progression through a series of increasingly powerful emotional states. This intensity is amplified by Noël’s elegant, febrile line. His touch is simultaneously tentative and assured; his expressive strokes, with their intricate junctions, are highly idiosyncratic. If this is a quest for transcendence, it is communicable only through strict abstraction, a condensation of reality to its essence. These are not diagrams for finished artworks, although they are closely related in composition to some of Noël’s large paintings; they are works of art in their own right, with the authority to exist independently as well as in series. Each individual work possesses, according to John Berger, “a unique, one-time-only, physical presence,” giving it the quality of a portrait.3 Each work is both a singular entity and an organic part of a larger whole.

Noël’s drawings and the paintings to which they relate evoke associations with the natural world. This series suggests trees branching in Mondrian-like abstract patterns against a sky modulated by changing moods of light and shadow, or perhaps by the extensions of a moving human body. Meaning resides in the subtle variations among the works, in the changing directions of the lines that, as Berger observes, “are always leading somewhere else.”4 Where else is the question at the core of the works’ mystery.

Notes

1. See the artist’s website, http://www.martinnoel.de/werkauswahl/index.html.

2. Nicholas de Warren, “Ad Infinitum: Boredom and the Play of Imagination,” in Infinite Possibilities: Serial Imagery in Twentieth-Century Drawings (Wellesley, MA: Davis Museum and Cultural Center, 2004), 11.

3. John Berger, “Branching Out,” in Martin Noël: Blau und andere Farben, ed. Peter Dering (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2003), 45–51.

4. Ibid., 45-51.

Bios

Amanda Beresford

Martin Noël

Amanda Beresford on Sol LeWitt

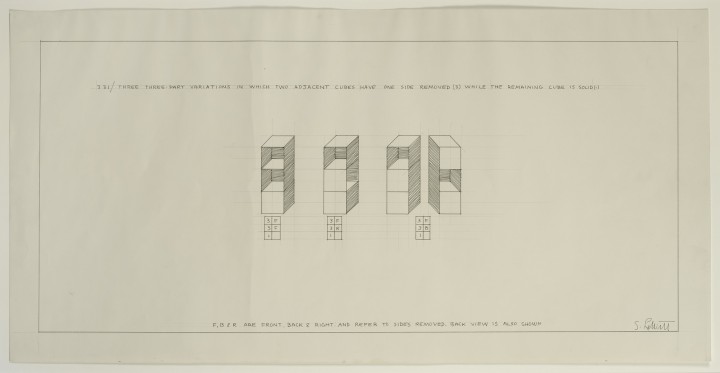

Figure 1. Sol LeWitt, Three-Part Variations on Three Different Kinds of Cubes 331, 1967

Ink and graphite on paper, 11 3/4 x 23 3/4 inches (29.8 x 60.3 cm)

© 2012 The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Sol LeWitt

by Amanda Beresford

In his 1967 essay “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” Sol LeWitt insisted on the primacy of the idea in the mind of the artist over the final artwork to which it led. The concept, he wrote, is the most important thing about the work; it is “the machine that makes the art.”1 Following LeWitt’s logic, any drawing or diagram produced by the artist is to be regarded as part of his thought process and thus occupies a privileged position in his oeuvre as a record of the artist’s ideas.

Three-Part Variations on Three Different Kinds of Cubes 331 (1967; fig. 1) is one of a series of drawings consisting of variations on three stacks of three cubes. Each drawing contains two lines of explanatory text and three box diagrams, which explain the system employed for each cube stack according to a coded alphanumeric key.2 This drawing is headed with a handwritten notation describing the system employed: “3 3 1 / THREE THREE-PART VARIATIONS IN WHICH TWO ADJACENT CUBES HAVE ONE SIDE REMOVED (3) WHILE THE REMAINING CUBE IS SOLID (1).” The structures are drawn in a precise, impersonal style, entirely uninflected by expressive intent. The strict perspectival rendering makes clear that these are three-dimensional objects translated onto a flat surface; a pale grid of ruled lines defines their edges and corners, articulates their uniform dimensions, and emphasizes the two-dimensionality of the paper, generating a geometric tension between actual flatness and implied depth. The text at the lower edge of the sheet explains the symbols in the key boxes below the cube stacks. LeWitt’s drawing and its rubric are clear and direct, claiming to be exactly what we see and no more. The artist lays bare the parameters of his system, and it is up to us to make what we will of it. The drawing functions, as LeWitt wrote, as “a conductor from the artist’s mind to the viewer’s”; its meaning as a study for sculpture is perhaps subsidiary to its role as an intellectual exercise for the artist.3

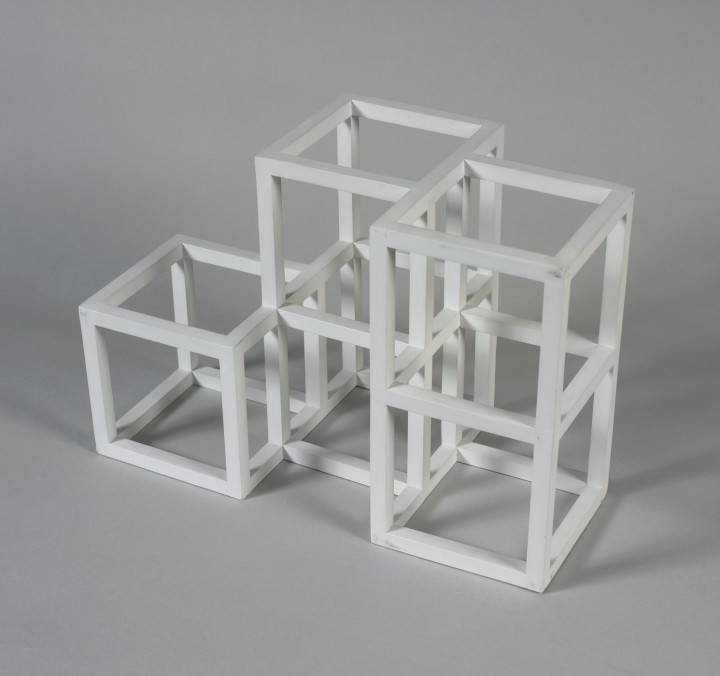

Figure 2. Sol LeWitt, Maquette for 1 x 2 x 2 Half Off, 1990

Paint on wood, 10 x 14 3/4 x 7 3/4 inches (25.4 x 37.5 x 19.7 cm)

© 2012 The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

LeWitt made a great many drawings as plans for three-dimensional structures based on incomplete open cubes; beginning in the late 1960s, he also made maquettes, such as Maquette for 1-2-2 Half Off (1990; fig. 2). This small-scale painted wood construction of five asymmetrically conjoined skeletal cubic modules, from which LeWitt “removed the skin,” reveals another variation on the realization of his system, emphasizing the artist’s foundational idea that the work of art can be realized in several ways—as drawing, as sculpture, or solely as concept, remaining in the mind of the artist.4 The stark simplicity of LeWitt’s sculptures and drawings was vital, he felt, since complex forms “would be too interesting” and might “obstruct the meaning of the whole.”5 He chose the cube as his base unit owing to its neutrality as well as to its simplicity. It is, he claimed, “relatively uninteresting,” lacking any emotive force, and has the advantage of being “immediately understood” as “uncontestably itself.”6 The cube functioned as a tabula rasa for the elaboration of the artist’s thought process, which in turn became the subject matter of his work. Like other Conceptual artists, LeWitt used language as a metaphor for this process: he spoke of the cube as both the “grammar” and the “syntax” of the total work—literally the elemental building block from which limitless variants could be constructed.7

Paradoxically, LeWitt stressed that his serial approach should not be regarded as rational, despite the formal logic of its visible expression: “Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists. . . . Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically.”8 Both the incompleteness of his cubes and their apparently endless permutations have been read as signs of the deliberate—even parodic—irrationality of his systems, notably by Rosalind Krauss, who believed, as Nicholas Baume has remarked, that LeWitt demonstrated a worldview that was “skeptical of any claims to universal truths.”9 Readings such as this—alongside John J. Curley’s claim that the cubes’ incompletion signals, among other things, “the inability of scientific thought to restore wholeness to society”—imply that LeWitt may have knowingly played with the relationship between the rational and the irrational as a form of social commentary.10 His drawings and sculptures suggest a process of endless serial production that remains incomplete, even futile, for all that LeWitt continued to make them.

Notes

1. Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” in Sol LeWitt: Critical Texts, ed. Adachiara Zevi (Rome: Libri de AEIUO, 1995), 78.

2. The drawing relates to an artist’s book by LeWitt: 49 three-part variations using three different kinds of cubes / 1967–68 (Zurich: Bruno Bischofberger, 1969). The book contains the prints 3-3-1 and 3-1-3, which are identical to two drawings in the Kramarsky collection: Three-Part Variations on Three Different Kinds of Cubes 331 (1967) and Three-Part Variations on Three Different Kinds of Cubes 313 (1968).

3. Sol LeWitt, “Sentences on Conceptual Art,” in Zevi, Sol LeWitt, 89.

4. Josef Helfenstein, “Concept, Process, Dematerialization,” in Drawings of Choice from a New York Collection, ed. Josef Helfenstein and Jonathan Fineberg (Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2002), 14.

5. Sol LeWitt, “Serial Project No. 1 (ABCD),” in Zevi, Sol LeWitt, 76.

6. Sol LeWitt, “The Cube,” ibid., 72.

7. LeWitt, “Serial Project No. 1,” 76, 75.

8. LeWitt, “Sentences,” 88.

9. Nicholas Baume, “The Music of Forgetting,” in Sol LeWitt: Incomplete Open Cubes, ed. Nicholas Baume (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 21.

10. John J. Curley, “Pure Art, Pure Science: The Politics of Serial Drawings in the 1960s,” in Infinite Possibilities: Serial Imagery in Twentieth-Century Drawings (Wellesley, MA: Davis Museum and Cultural Center, 2004), 33. Sarah Louise Eckhardt observes that the cubes’ potential for variation reveals the subjective arbitrariness of LeWitt’s decisions, subverting his systems’ apparent order. Sarah Louise Eckhardt, “Sol LeWitt,” in Helfenstein and Fineberg, Drawings of Choice, 82.

Bios

Amanda Beresford

Sol LeWitt

Amanda Beresford on Dan Flavin

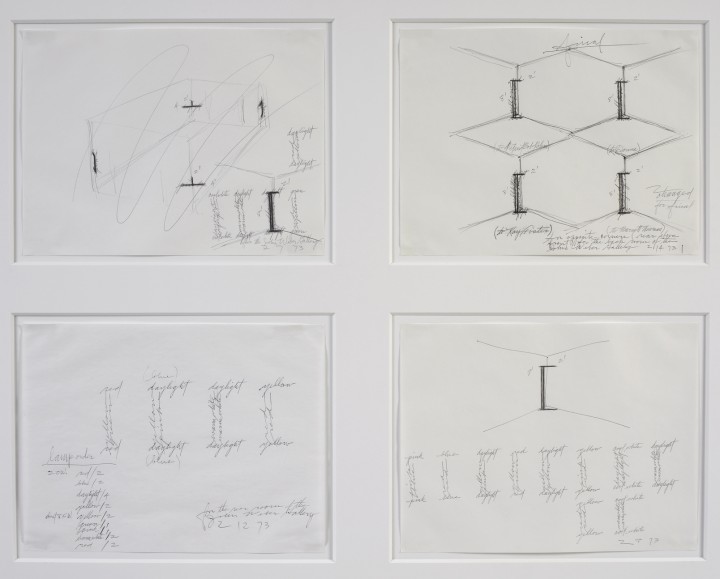

Figure 1. Dan Flavin, Four drawings for the John Weber Gallery

Feb. 7, 1973; Feb. 8, 1973; Feb. 12, 1973; Feb. 14, 1973, 1973

Ballpoint pen on typing paper, 4 sheets, each 8 1/2 x 11 inches (21.6 x 27.9 cm)

© 2012 Stephen Flavin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Dan Flavin

by Amanda Beresford

One of the leading practitioners of Minimal art, Dan Flavin was known from 1963 until his death in 1996 for his sculptures and installations made from fluorescent light fixtures and other commercially available materials. Made in 1973 for an installation at the John Weber Gallery in New York, this group of four working drawings (fig. 1) anatomizes Flavin’s method of working with fluorescent tubes to create installations in which light defines and transfigures space. The annotated drawings trace the progression of the artist’s concept from its initial trial layout to the final articulation of the installation, functioning both as records of his thought process as he elaborated and changed his design and as diagrams for the construction of the work. The drawings thus enable the viewer to follow and comprehend, in several stages, Flavin’s unique creative path.

Flavin recorded his ideas for artworks in notebooks that he carried everywhere, sketching layouts and annotating them extensively with technical details. These constituted his primary creative input into the final installations, which were ultimately executed by technicians. In contrast to his detailed and specific working drawings, the end products, constructed of store-bought materials, de-emphasized any physical intervention on the part of the artist. Flavin underlined the importance of drawing to his work in 1973, the year he made these sketches: “I have come to understand that, for me, drawing and diagramming are mainly what little it takes to keep a record of thought…. Within my reciprocating system for fluorescent light such continuous retention is constantly required.”1

Unlike some of the highly finished presentation drawings in Notations (for example, those by Mel Bochner and Sol LeWitt), Flavin’s sketches are rough and spontaneous, exposing the artist’s hand and thus taking on an autographic quality. The idiosyncratic, personal nature of the sketches appears in distinct contrast to the industrial finesse of Flavin’s installations. Each drawing reveals the artist’s consciousness of time and space: all are dated, so the order of their execution can be established, and three are inscribed with a variant of “for the rear room of the John Weber Gallery.”

The three earliest drawings show various projected arrangements for the light-tube assemblages, annotated with dimensions, wattage values, potential color combinations, and locations in the corners of the room. One room layout is scrawled over, marked as rejected. In the fourth drawing, headed “final,” several corner placements are arrayed in a decorative pattern, their perspective angles forming a grid of open and closed diamonds and hexagons. This is simultaneously instructive, aesthetically pleasing, and visually deceptive; the drawing’s aesthetic qualities work against its utilitarian nature as a technical diagram. Referring to the arrangement of the light fixtures, Flavin said, “I never neglect the design.”2 Here he established a tension, also apparent in the finished artwork, between its aesthetic effect and the industrial materials and method of its construction.

Handwritten text is integral to each drawing, providing technical instructions and serving as a structural component. Flavin constructed the forms of his light-tube assemblages from the words that indicate the colors of their lamps: red, yellow, green, pink, blue, daylight, warm white, and cool white. The written words have a double signification, indicating both the color of the light to be produced and the form of the object producing the light. Flavin made language a surrogate for object, privileging the conceptual over the physical nature of the artwork in drawings that chart the concept’s evolution.

The trials, rejections, and hesitations that these drawings acknowledge emphasize process, exposing the role of contingency and choice in Flavin’s mode of creation. These rapid working sketches on common notebook or typing paper were essential to his methodology. He made his drawings as a means of thinking through and recording his installations, but for the viewer they elucidate the relationship of the artist’s working process to his finished work.

Notes

1. Dan Flavin, quoted in Isabelle Dervaux, Dan Flavin Drawing (New York: Morgan Library and Museum, 2012), 113.

2. Dan Flavin, “Some Other Comments . . . ,” Artforum 6 (December 1967): 23, quoted in Eun Young Jung, catalog entry for Jill’s Red Red and Gold of December 9, 1965, in Drawings of Choice from a New York Collection, ed. Josef Helfenstein and Jonathan Fineberg (Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2002), 44.

Bios

Amanda Beresford

Dan Flavin