Matthew Bailey on Agnes Martin

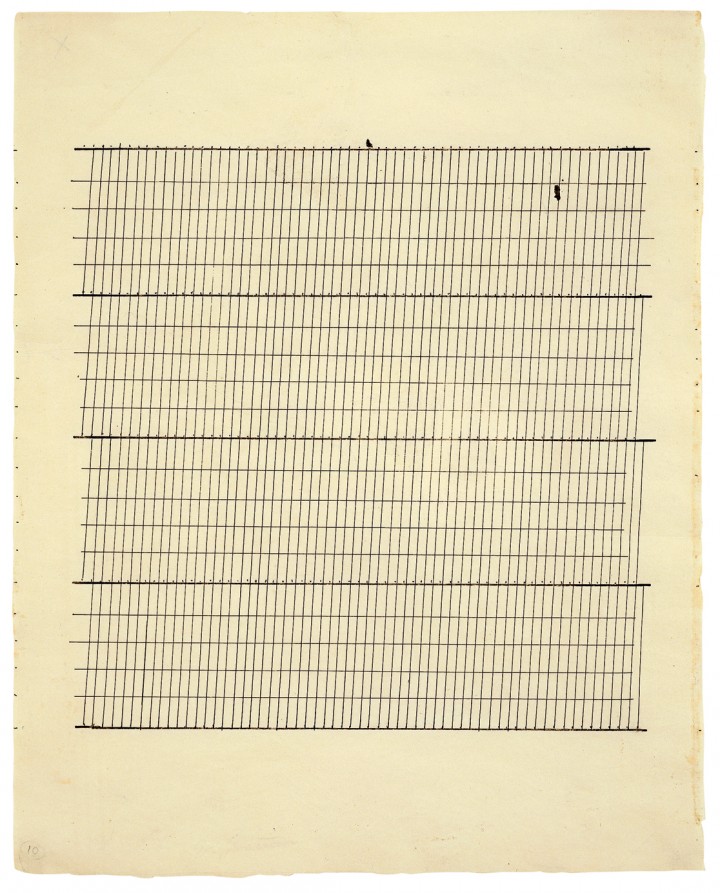

Figure 1. Agnes Martin, Aspiration, 1960

Ink on paper, 11 3/4 x 9 3/8 inches (29.8 x 23.8 cm)

© 2012 Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

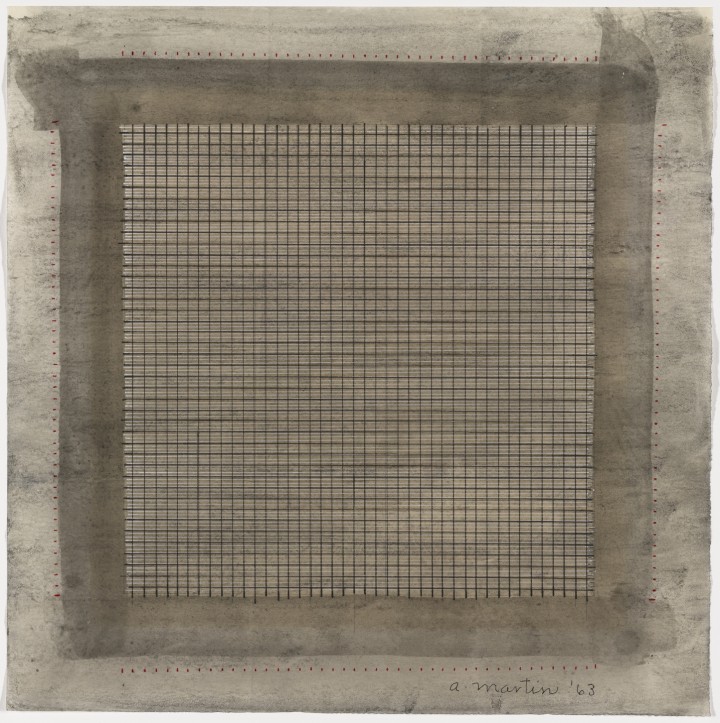

Figure 2. Agnes Martin, Wood I, 1963

Watercolor and graphite on paper, 15 x 15 1/2 inches (38.1 x 39.4 cm)

Gift of Sally and Wynn Kramarsky, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2012 Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Agnes Martin

by Matthew Bailey

Agnes Martin was one of a number of artists whose unique brand of geometric abstraction was positioned apart from the heroic, fluid gestures of canonical Abstract Expressionism, which were thought to symbolize the inimitable psychic and somatic expressions of the individual artist. While maintaining a belief in art as a specialized sphere of aesthetic experience, Martin looked to more impersonal compositional strategies to suppress artistic subjectivity, instead privileging the relationship between the viewer and the work of art. To this end, in the early 1960s she began systematically using the compositional logic of the grid as a template for her aesthetic investigations. The three drawings on view in this exhibition exemplify her serialized exploration of formal variation, guided and limited by the geometric configuration of the grid. The monochromatic Aspiration (1960; fig. 1) is anchored by five horizontal lines drawn with pen and ink in the center of the sheet. Within each of these bands, Martin drew a series of more delicate lines: four evenly spaced horizontals of slightly differing lengths are contained within or protrude from the dense pattern of slanting vertical lines that they bisect. Although at first glance these patterns of lines appear perfectly parallel and congruent, a closer look reveals slight inconsistencies in angle, spacing, and length, as well as in thickness and weight. Portions of the lines are broken or faded due to alterations in the pressure of the artist’s hand.

The tension between the rigid system of the grid and the graphic variations permitted by Martin’s subjective choices and treatment of line becomes more complex in Wood I (1963; fig. 2). Here she overlaid in pencil a square grid on top of a thin black wash with subtle irregularities in tone and texture. Behind the graphite grid and over the wash, she also drew a patterned series of faint white horizontal lines. These lines generate an optical vibration in the graph, which is bound by dark, casually applied bands of wash extending beyond the parameters of the square.1

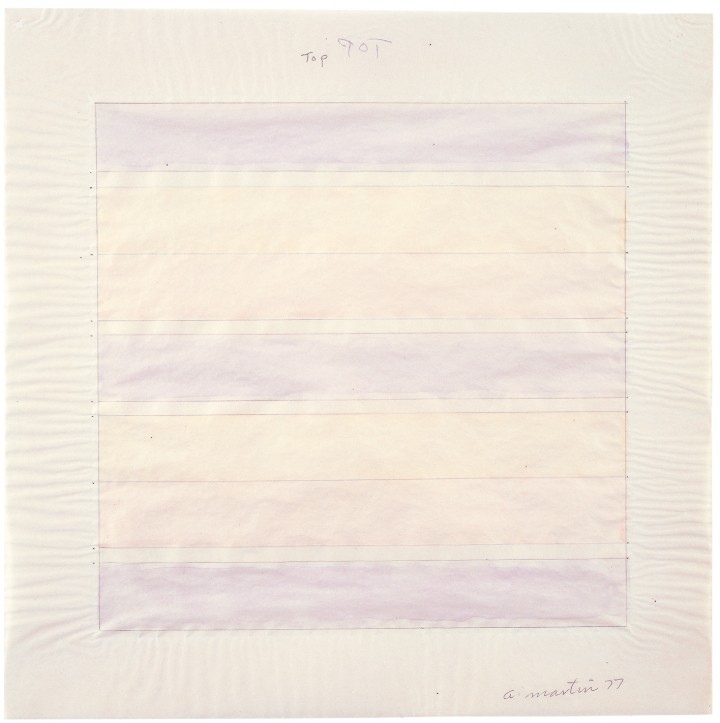

Figure 3. Agnes Martin, Untitled, 1977

Watercolor and graphite on paper, 15 x 15 1/2 inches (22.9 x 22.9 cm)

© 2012 Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Martin’s untitled drawing of 1977 (fig. 3) is distinct from these two earlier works in its exploration of the effects of watercolor. It is also representative of her later departure from the strict parameters of the grid and her experimentation with using squares and rectangles to create geometric configurations. The work presents bands of thinned pink, blue, and red wash framed within a lightly drawn square and overlaid by a rhythmic pattern of horizontal lines. Bleeding into the paper, with faint variations in saturation and tint, the luminous colored bands give the work a mystical, atmospheric quality that seems at odds with the rational, geometric contours structuring the composition.

Martin’s intimate and infinitely subtle works on paper beg close examination of their nuanced perceptual effects. Her fixation on the grid and geometric forms was driven by an interest in creating an elevated aesthetic experience with limited, systematic means. Despite the seemingly rational nature of her system, Martin believed in art as a realm of transcendent experience, much like nature itself. Titles such as Aspiration or Wood I allude to these sources of inspiration, her work reaching for the exalted just as it reflects the conflict between order and the arbitrary in nature. “All great artwork attempts to represent our joy in moments of clarity and vision,” she wrote in a letter to Barbara England attached to the back of Wood I. “Please study your response to art very carefully (and to everything else) as it is the road to self knowledge and truth about life.”2 For Martin, art was a spiritual endeavor, and she was devoted to making viewers conscious of “a wide range of emotional responses that we make that cannot be put into words.”3 Her concern with eliciting experiences of exultation and self-revelation, however—pointing to that “something which isn’t possible in the world / More perfection than is possible in the world”—hinged on the suppression of her subjective self, and the grid exemplified this “egolessness.”4 This logical system—together with sensuous variations in quality of line, sensitive shifts in tone or texture, and nuanced relationships between materials—pushed art beyond the trace of self-expression and toward the embodiment of universal experiences of truth, beauty, and perfection.

Notes

1. The red plotting marks along the outside edges of the image were likely used as a guide for the mechanical application of lines with a ruler.

2. Agnes Martin, quoted in Eun Young Jung, “Agnes Martin,” in Drawings of Choice from a New York Collection, ed. Josef Helfenstein and Jonathan Fineberg (Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2002), 106.

3. Agnes Martin, “Beauty Is the Mystery of Life,” in Agnes Martin, by Barbara Haskell et al. (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1992), 10–11.

4. Agnes Martin, quoted in Aline Brandauer, “Bearing Witness,” in Agnes Martin: Works on Paper, by Aline Brandauer, Harmony Hammond, and Ann Wilson (Santa Fe: Museum of Fine Arts, Museum of New Mexico, 1998), 13.

Bios

Matthew Bailey

Agnes Martin