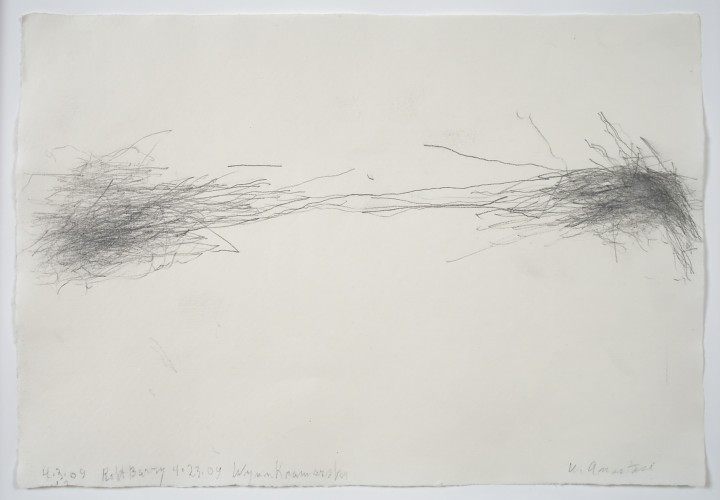

William Anastasi, Untitled (Subway Drawing), 2009

Graphite on paper, 8 x 11 1/2 inches (20.3 x 29.2 cm)

© 2012 William Anastasi

William Anastasi

In Conversation with Rachel Nackman

March 2012, New York

Rachel Nackman: When did you begin making subway drawings? What was the genesis of that activity?

William Anastasi: The genesis of the subway drawing was the walking drawing. These were done holding a pad and walking, watching where I was going rather than watching the pad. I started doing this in Philadelphia in the early 1960s. To my memory, the pocket drawings weren’t started until I was going to films at MoMA, so I was here in New York by then. And the pocket drawings at films led to pocket drawings in the subway. Those reminded me of some different subway drawings I had done before coming here.

RN: You also made subway drawings in Philadelphia?

WA: I made subway drawings in Philadelphia, and I made walking drawings in Philadelphia. The only one of the three types of drawing that wasn’t started there was the pocket drawing.

RN: How did you decide to make the subway drawings and walking drawings in Philadelphia?

WA: I love walking. I find that walking does something to my thinking, to my mental process, that is different from sitting or lying down. I learned that about myself very early. I was already a runner, but walking is extremely different from running, and I think that’s one of the important things about it. I’ve tried running drawings and I don’t like it so far.

RN: It sounds difficult.

WA: Yes. Maybe I’m afraid I’ll fall on my face; I don’t know. But the walking drawings gave me an idea. When there’s motion, let that motion, rather than predetermination, be the energy for the drawing—rather than consulting the aesthetic prejudice of the moment, which we usually do when we draw if our eyes are open. With the subway drawings, my eyes are closed, for the most part, or looking at the floor or the feet of the people across from me.

Right from the beginning of the process, I wasn’t interested in looking. I think that was part of my original idea, because with the walking drawings you have to watch where you’re going, so you’re automatically not looking. I think that’s why the walking drawings had something to do with the subway drawings—it makes a lot of sense.

William Anastasi, Untitled (Subway Drawing), 1973

Graphite on paper, 7 5/8 x 11 1/8 inches (19.4 x 28.3 cm)

Collection of the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum

© 2012 William Anastasi

RN: When you started making your first walking drawings in Philadelphia, were you walking with a destination?

WA: For the most part, I was walking in the big apartment I had. I think I was embarrassed to do it outside in my neighborhood. I’m not embarrassed to do it in New York, though, walking to the Hudson River, although sometimes people comment. One time, a fellow came up next to me as I was walking because he was very interested in what I was doing and had questions about it.

RN: Did you stop and talk to him?

WA: I didn’t stop; I kept walking. But we talked while I kept walking and drawing.

RN: You can do a lot of things at once.

WA: I’ve done numerous subway drawings, as you know. I don’t get on the subway without doing it, because I find it’s another form of meditation–a kind of meditation I learned before I actually learned to meditate.

RN: When you make a subway drawing, generally there’s a destination that you write along the bottom.

WA: I usually put where I’m going, or whom I’m meeting, along the bottom. I have one here today that has Wynn Kramarsky’s name on the bottom.

Someday, I would like to do a show titled The Idiots, They Were Making Fun of You. The reason for that is that I used to play chess with John Cage every day. He knew my subway drawings, and it was a great honor that the first things you saw when you walked into his home was a group of three subway drawings. He liked the idea very much.

In my memoir The Cage Dialogues, from 2011, I talk about the time that John asked, one day, “Are you going home by subway?” I said yes. He asked, “Are you going to do a subway drawing?” I said yes. He said, “Could I come?”—it was amazing that he wanted to—and I said yes, of course. My eyes were closed during the whole drawing, and when we got off the train, John said, “The idiots, they were making fun of you.” It was extremely uncharacteristic of him—extremely—to ever talk that way about someone. It would be an interesting thing, for this centennial year of Cage’s birth, to do a show somewhere with that title.

RN: What would be in that show?

WA: Well, I guess my work that people make fun of. For example, I’m sure that would include the walking drawings. I’m sure some people think I’m quite crazy. Or the subway drawings—when my eyes open as the train stops, it does look as though some people think I’m loony.

RN: You are very conscious of the fact that people are watching you when you make the subway drawings.

WA: There’s no question. Thousands and thousands of people. I’m sure it’s true every time I’m on a crowded subway. Some people obviously like it and don’t just think I’m nuts. But some think it’s strange—“What’s wrong with that guy?” And maybe, if they’ve ever done a drawing themselves, some think, “Oh, that’s a nice idea.”

RN: You’ve said that your day tends to be better when you make a subway drawing.

WA: Usually it is. It is so true that, at a stressful time, I’ll find myself searching for an excuse to take the subway down to New York Central Art Supply, or somewhere else.

RN: Can you tell us what it is about the daily process of making the subway drawing that appeals to you?

WA: I think I do know, in my case, what appeals to me. It was many years after I began the subway drawings that I learned a meditation practice. And a meditation practice is very valuable if you do it every day, so much so that the person who taught me advised, “If you don’t have half an hour, do five minutes, no matter what. If the house is burning down, do five minutes.” That’s the way it was put. And it’s true. There’s something about the quotidian that is valuable. And I draw every day.

I’ve been drawing every day, probably since grade school, so it’s kind of part of me. As a child, I’d even put the date and my name on my drawings, whereas when I thought of becoming an artist as an adult, at first I wouldn’t put my name on them because I dared not think I was really an artist. I was afraid to call myself an artist until August 15, 1960. That’s when, as an adult, I first put the date and my name on a drawing. It was like jumping off a building.

RN: Do you remember what drawing that was?

WA: It was an abstract drawing. That’s all I remember. I still have it somewhere. It was certainly made before I was making walking drawings. Before the walking drawings, my drawings, when they were abstract, were from my mind, or from something if something was there to draw. I would do drawings of my wife at the time and of my kids.

RN: And then the walking drawings happened in the early 1960s, after you put that first date on a drawing.

WA: Oh, yes. My mother had a mantra—she’d say, “Of course, the best thing you can be in this life is an artist.” That is literally one of my earliest memories. I don’t know where she got that idea, but it’s one of the things that made me afraid to sign something as an adult.

When I learned meditation, it was then that I thought I’ve been, in a way, meditating already, by drawing virtually every day.

RN: When did you learn meditation?

WA: Dove Bradshaw and I have been together for something like thirty-seven years. It was right after I met Dove that I learned to meditate. She had studied meditation—Transcendental Meditation—and she had been practicing for a couple of years before we met. In the next ten years, she fell away from it. But in 1984 we read a New York Times article that said that even if you didn’t think it was working for you it actually was, that it was very healthy. It was then that I took the teaching more seriously, and that got us both starting again. Dove had a mantra. Since that was her practice attitude, I made up my own mantra, which happened to be row-dee. At the recommendation of my son Lawrence, I went to the Shambhala Center, which involves meditation with your eyes open, different from the kind of method I learned from Dove.

The Shambhala method is very simple: sit eleven or twelve inches off the ground with your legs crossed. You look at a clock or watch, and you say to yourself that you’re going to do this for a half hour. Then you settle your view on an area or a spot on the floor—so your eyes are not closed. You keep your eyes, as much as you can, on that area or spot. You settle your view there and pay attention to your outbreath, and that’s all you have to remember. Is your breath smooth? Is it rough? Is it fast? Is it slow? Is it the same as always? You simply pay attention. As soon as your mind is wandering about some unpaid bill or some difficult romance, you calmly go back to your outbreath. When you think it’s roughly half an hour, you shift your glance to the watch. When you first begin, you’re going to look up after fifteen minutes, and you’re going to realize it’s only been fifteen minutes, but eventually you get very good at it. I’m much better at it after these years. I can usually nail it within a minute or two.

I was already doing the subway drawings when I learned meditation, but the connection between them had never occurred to me. I knew I liked making the drawings. I knew it was valuable for me. I never would have used the word meditation, but after a while, I realized, “You’ve been doing your own form of meditation.” Blaise Pascal said, “All the troubles in the world can be traced to man’s inability to sit alone quietly in a room.” If you think about it, if enough men meditated, you wouldn’t have war, you wouldn’t have murder, you wouldn’t have all the troubles in the world. It can all be traced to man’s inability to sit quietly in a room. We’re busy beavers.

William Anastasi, Untitled (Pocket Drawing), 2008

Graphite on paper towel from The Modern restaurant, 16 7/8 x 16 7/8 inches (42.9 x 42.9 cm)

© 2012 William Anastasi

RN: Can you walk us through the process of making a pocket drawing?

WA: You fold a piece of paper until it can fit in your pocket, and then you put it in your pocket, and you use, usually, a 6B or 8B pencil. Soft. I just put my hand in my pocket, feel the paper, and draw. If it’s a pocket drawing, I’m usually also walking.

RN: When you’re making the walking pocket drawings, do you move the pencil yourself or do you just let the movement of your walking move the paper?

WA: To some extent both the pencil point and the folded paper are affected.

RN: When do you decide that you will pull out the paper, unfold and refold it?

WA: That’s hard to answer, because it’s not as though I decide. In other words, I’m not consulting the drawing and saying, “Is that enough?” The process is—what would you call it—phenomenological?

This particular drawing was inspired by the fact that it says “The Modern” on this napkin. I thought it was very funny that this was printed on that kind of paper. I still think it’s funny. I thought, “If it’s something funny, it’s a good thing to do a pocket drawing on.” There is also the thickness of the napkin to consider, which I found charming. If I make a pocket drawing with a different kind of paper, the wrinkles from folding it are more lasting. With this kind of napkin paper, the wrinkles for the most part disappear, so you see the drawing in a different way.

RN: This paper is almost like a textile.

WA: Yes, it behaves more like half fabric, half paper. In the pocket it works fine, because it conforms to your thigh and your hand. And then when you take it out, it doesn’t look like it was in your pocket because of the kind of paper it is. So I thought that was kind of interesting—that afterward it is going to look different from the normal paper I use.

RN: It’s the ideal support for your process.

WA: Yes. Except I like the wrinkles just as much as the no wrinkles. I just liked the idea that it was different. Some have wrinkles and this doesn’t: I thought that was something important.

RN: Have you found that your process of making a subway drawing has changed over time?

WA: The fact is, I thought of the subway drawings as some kind of therapy when I first started making them. I didn’t take them as seriously as I did my other drawings. I really thought drawing was drawing, and subway drawing was something else.

RN: Do you still feel that way?

WA: No. I now think it is part of what I do. In my other work I try to have the same kind of spontaneity that I see on the page when I do a subway drawing. It very often surprises me, even after all this time. I’m trying to get that spontaneity into the other work, which I make when I’m looking. But I’m never looking at the subway drawings while I’m doing them, whether my eyes are open or shut.

RN: So when you’re completely done with a subway drawing, then it’s revealed to you; at that point you see.

WA: I’m never finished with them. I can always see one and say, “I’ll do another trip downtown on this.”

RN: Do you see your subway drawing practice as in some way documenting a part of your life?

WA: No. Not consciously. I guess I don’t think that about any of the work. That’s for after I’m gone. People will probably do that later—but no, I don’t. That thought has not occurred to me.

RN: You just think about what you’re doing when you’re doing it, on a daily basis?

WA: I think artists usually do. I think artists are the opposite of curators. Good artists live in the present. We’re always changing; our taste is changing, our method and our madness are changing. Artists are the opposite of curators, probably, because curators are frozen. They specialize in a certain area. I’m not that way.

I still wonder whether I am an artist. And I think it’s the healthiest thing in the world, no matter what has happened to me. I think it’s because of my mother saying that the best thing anyone can be in this life is an artist. It’s as though a part of me, almost eighty years old, is saying, “Well, Mom, I wish I was one.” It almost brings tears to my eyes, but it’s true. I think I’m still trying to prove to her that I’m an artist, because I haven’t proven it to myself.

Bios

William Anastasi

Rachel Nackman